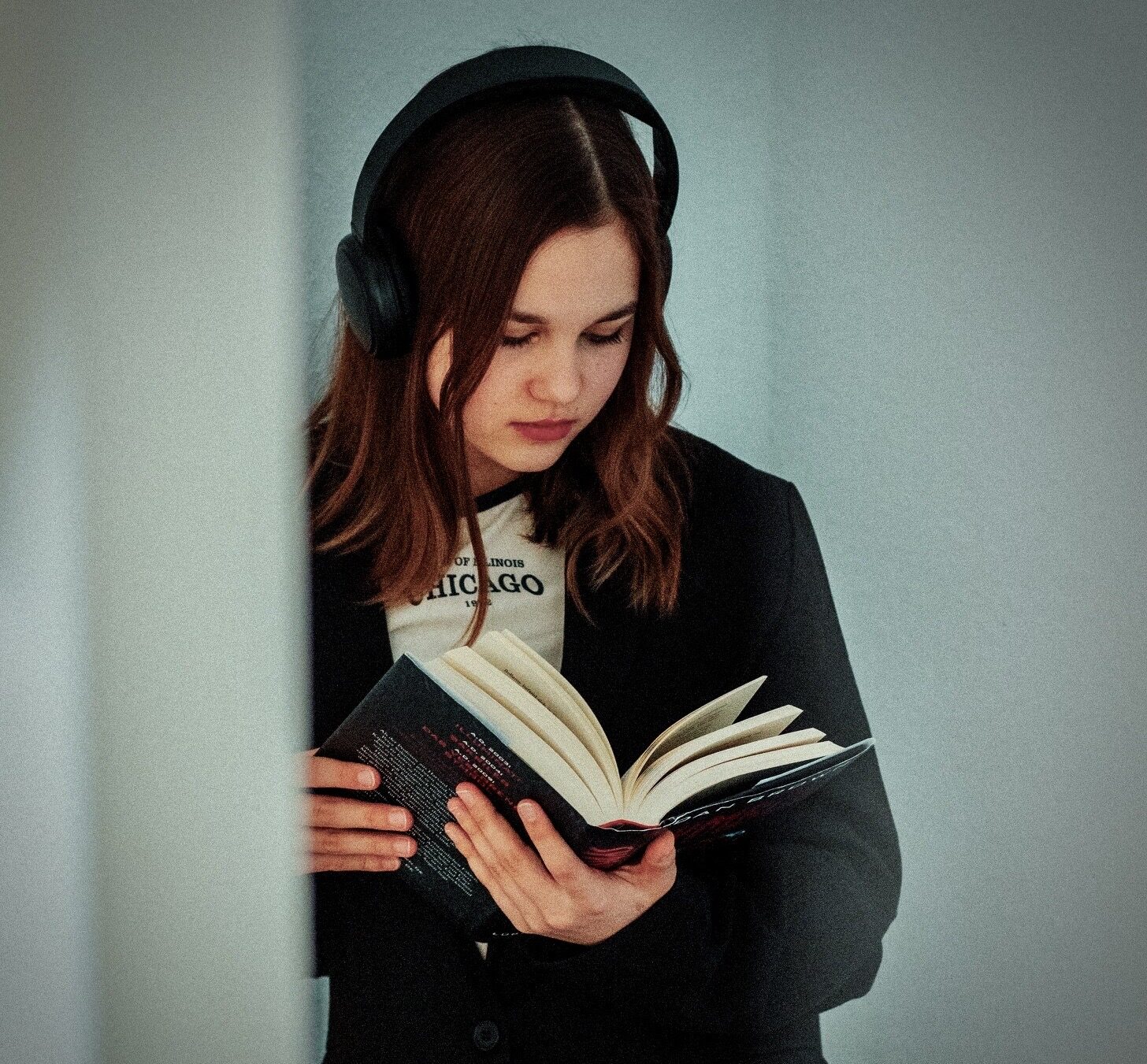

What Actually Happens When Young People Read Disturbing Books.

Literacy scholars Gay Ivey and Peter Johnston are co-authors of the recently released book Teens Choosing to Read. And, they point out in a recent blog post for Columbia University’s Teachers College Press that what actually happens when young people read “disturbing books” has been “lost in the political battles over ‘educationally suitable’ books.” [1]

Well… Ivey and Johnston have studied this, and here’s what they learned: The students they interviewed, most of whom said they previously read little or nothing, “started reading like crazy” both in and out of school. And, their reading achievement improved. They also reported improved self-control, as well as developing more, and stronger, friendships and family relationships. Students also reported being “happier. Yes, happier.” [2] That’s no small consideration, given the recent rise in teens with anxiety disorders.

More than 20% report being bullied, and over 60% have abused alcohol by 12th grade. About one out of six young adults indicate “they made a suicide plan in the past year,” a 40% rise in the past decade.[3] Black students who reported attempted suicide rose 50% in 2019. These figures are astronomically higher for LGBTQ+ students. Reading and talking about books that are personally meaningful can literally provide a lifeline for teens. [4]

Public School Superintendents list the post-pandemic decline in reading achievement among their biggest concerns, closely followed by bullying and disruptive behavior, as well as students’ mental health. [5] Sadly, banning “disturbing books” takes a way one of the best tools educators have for addressing these concerns.

The article below is a more detailed look into Ivey and Johnston’s findings, with insights directly from students, teachers, and parents. They’ve have been leaders in their field for decades. So, we should pay attention to what they have to say on the subject of books and reading.

Emerging Adolescence in Engaged

Reading Communities

By Gay Ivey and Peter Johnston

This article addresses possibilities for children’s development

as they edge their way into young adult literature within

engaged reading and engaged classroom communities.

.

.

.

ome years ago, in the early days of some research we were conducting in a middle school (Ivey & Johnston, 2013, 2015), Gay began to read Ellen Hopkins’s Identical (2008), a book requested by many of our eighth- grade participants. We were trying to understand what middle school students do when they have available to them both a wide range of books speaking to issues central to their lives and the free will to do what they want with the books, if anything at all. Like earlier books from Hopkins that were catalyzing mass reading and conversation in the community we studied, such as Crank (2004) and Burned (2006), Identical was unavailable in their school library, so we would need to buy it.

Less than a quarter of the way through the reading, Gay closed the book. So far in the story, a verse novel told by alternating narrators who were twin sisters, she had learned that one sister was being sexually abused by the father, and the other, feeling ignored, appeared to be envious of that relationship. That was all she needed to know to make a firm decision about whether or not that book would make the cut. That was a resounding no.

The next morning, she broke the news to students that she had major reservations about making Identical available. She explained what she had learned in the book to that point and how the thought of twelve-and thirteen- year- olds reading about such mature matters made her anxious for them. That was fine, they assured her, and they totally understood her concerns. Within a week, though, several copies were circulating around the school. Students had pooled their resources and were taking matters into their own hands. One of their teachers asked Gay if she had ever finished reading the book. “That’s too bad,” he replied when she said she had not, “but that’s your loss.”

No spoilers here, but Identical shortly became one of Gay’s all- time favorites. More important, though, was understanding the significance for students, and this was made clear in an end-of- year interview. Turning the tables on Gay, Talia (all names are pseudonyms) asked simply, “Why didn’t you want to buy us Identical?” But before Gay could answer and because Talia already knew Gay’s initial misgivings, she explained:

![]() At the end, it was [the main character’s] boyfriend that stood by her, even when it seemed like she was crazy. That’s how a friend should be. When we got to middle school, people who used to be friends weren’t anymore. Everybody starts judging each other by what’s on the outside. Don’t you think we need books like that so we can talk about it?

At the end, it was [the main character’s] boyfriend that stood by her, even when it seemed like she was crazy. That’s how a friend should be. When we got to middle school, people who used to be friends weren’t anymore. Everybody starts judging each other by what’s on the outside. Don’t you think we need books like that so we can talk about it?

This book deals with incest and other issues that make us and other adults nervous for children, but we cannot really know how readers find meaning. Talia’s comments suggest that at least in part, she was drawn to the intricate relational dynamics among the characters and saw them as indistinct from those of her own social world. Although the complexity of the characters’ lives might not have paralleled Talia’s life (but would those of some of her peers), becoming intertwined with them allowed her to empathize and perhaps see others outside of the narrative differently. So much for trying to comprehend younger readers’ experiences through adults’ eyes and minds only.

We imagine, though, that others who parent, teach, and study young adolescents, especially those even younger than Talia, experience some degree of trepidation at the thought of their children being drawn to books offering glimpses into complicated relationships, sexual situations, violence, substance abuse, strong language, and other realities most children gain at least awareness of by their teen years. In this article, we will share what we have learned from children edging their way into young adult literature. Most of our work has centered on eighth-grade students and, of course, some of the literature we will mention would not be of interest to fifth and sixth graders. Our point, though, is not to suggest what pre-and young adolescents should read, but instead to shed some light on why and how they read in order to inform practice and reduce anxieties.

We will start by describing the range of ways students tell us they use characters and their moral dilemmas as tools in their own lives. Next, we explain how we have theorized students’ experiences with text when they are engaged in reading narratives. We illustrate how conversation through and about texts and the discursive environment of the classroom shape students’ experiences with these texts. Finally, we offer some suggestions for supporting the engagement of readers emerging into adolescence.

Children’s Views on Learning from Narratives

Across hundreds of interviews with middle school students over a six-year period (Ivey & Johnston, 2013, 2015), we documented myriad accounts of engaged reading much like Talia experienced. In these cases, students were in language arts classrooms where teachers resisted assigning specific books, supporting instead students’ explorations of texts they chose themselves and the conversations that emanated within and around those readings. Consequently, students felt both a sense of relevance and a sense of autonomy; that is, they were pursuing what mattered to them. These are conditions essential for deep engagement in reading (Guthrie, Wigfield & You, 2012).

Because no specific book was required and because no assignments were attached, students could abandon any book they did not like. In our experiences, students did not persist in reading a book they did not want to think about, and those they did read were undeniably offering them new information. For instance, several children reading A Child Called It (Pelzer, 1995) have explained what a sobering experience it was to realize that a mother might abuse her own son.

We might pause here to consider that children (and adults) unavoidably encounter disturbing narratives, and in surprising places. A recent news story centered on live- streaming video of nesting osprey is a great example. Internet viewers tuned in regularly to observe the development of babies from hatching to the moment they could take flight. In one instance, though, viewers became panicked as they saw, in real time, a mother osprey gruesomely attacking her own babies. Their worry turned to outrage when their pleas for rescue were rejected on the advice of osprey experts. Intervention, they said, is called for only when the harm is induced by humans.

In addition to being joyful, compassionate, and hopeful, human nature can also be surprising, and children are keen to explore these complexities of humanity. In fact, we have found students who routinely rejected books with happily ever after endings because they were left with little to ponder. We encountered other students who remained fixed on lighthearted series books through the middle grades, but turned their attention to more complex books once they heard and participated in conversations about them among their peers.

Students did confess that the texts they chose were somewhat alarming, but they maintained that this was not a reason to set a book aside. In fact, it was part of the appeal. But before adults find the idea of children reading “disturbing” books, well, disturbing, it makes sense to consider how children describe the consequences of this reading.

First, children explain that vicariously living through characters’ dilemmas and weighing their options makes them consider how they are navigating their own present and future lives. For instance, Jeremy experienced Homeboyz (Sitomer, 2008) and its main character this way:

![]() It, like, takes you through stages of him growing up, while you’re, at the same time you’re reading the book, you’re thinking about him growing up. So, that makes you want to grow up with him and, like, be mature and not do, like, stupid stuff. (Ivey & Johnston, 2013, p. 270)

It, like, takes you through stages of him growing up, while you’re, at the same time you’re reading the book, you’re thinking about him growing up. So, that makes you want to grow up with him and, like, be mature and not do, like, stupid stuff. (Ivey & Johnston, 2013, p. 270)

Numerous students have shared with us that particular narratives made them rethink drug experimentation or gang involvement— both possibilities they were already facing.

Reading about characters experiencing phenomena at the far edges of students’ own experiences is quite useful because it creates the opportunity to think through the consequences before they encounter similar situations head on. A student in an earlier study (Ivey, 1999) explained that characters should be a few steps ahead of her to stay relevant. By sixth grade, Casey had reached the age of characters she loved in fourth and fifth grades, and she complained, “I’m like them now. And I used to think, like, Wow! And now they ain’t interesting no more” (Ivey, 1999, p. 182).

Second, books that portray the complexity and sometimes the difficulty of what it means to be human— and this applies to readers of all ages— allow a range of readers to work with issues heavy on their hearts and ever-present in their lives. Carmela, who at age 11 lost her mother, considered Far from You (Schroeder, 2009) not only a comfort, but also a tool for working through the grief that permeated her world. Children at this age also are becoming more aware of social, economic, and political unevenness, and narratives bringing these issues to the surface help readers consider who they are and wish to be in relation to the world. When Maisha read The Rose That Grew from Concrete (Shakur, 1999), she reflected, “. . . it makes me think about how [Tupac’s] environment was growing up. I mean, I lived it [… and] his words reminded me of my own self in a way.” She continued, “It makes me feel I should be more thankful and take more responsibility and doing things that I think are right and trying to help other people out [. . .]. I feel like I have a way in life of helping a lot of people” (Ivey & Johnston, 2013, pp. 263– 264). The uncertainties about her own life that Maisha revealed in conversations about this text also helped her peers relate to her in more productive ways.

Third, when children experience new and sometimes unsettling information about the world through the eyes and minds of characters experiencing it firsthand, they become more sensitive to what others endure. Thus, as they are learning about the world through narratives, they are also learning more about the complexity of humans within it. As Aurelia put it:

![]() I never knew how alone some people feel, or what it’s like to be in a mental hospital. Someone who attempts suicide, I don’t know how they feel, so [reading] helps me understand how they feel, and it gives me new ways to view life.

I never knew how alone some people feel, or what it’s like to be in a mental hospital. Someone who attempts suicide, I don’t know how they feel, so [reading] helps me understand how they feel, and it gives me new ways to view life.

We hear from adults who are concerned that books “teach” what they would not want students to learn. Indeed, we are quite certain that the stu-dents who have shaped our thinking were changing, and that the books made available to them contrib-uted powerfully to these transformations. To worry that children might actually engage in risky, self- destructive, or unethical behaviors because characters do, though, would suggest that reading is an activity of transmission. Students themselves are quite articulate about the falseness of this notion. In fact, they reject this worry as foolhardy. For instance, venting over her parents’ opposition to her reading choices— books they had not read—Betsy explained:

![]() I think most of the books I read have life lessons. Like Crank. When I read those [books by Ellen Hopkins], it’s not telling you, “Hey, go out and do drugs and have sex and stuff.” It’s telling you about how bad their life is if you do this stuff. What my parents don’t get is that it’s teaching me things that are good for me. It’s in a positive way, but they think it’s in a negative way. And I don’t think so.

I think most of the books I read have life lessons. Like Crank. When I read those [books by Ellen Hopkins], it’s not telling you, “Hey, go out and do drugs and have sex and stuff.” It’s telling you about how bad their life is if you do this stuff. What my parents don’t get is that it’s teaching me things that are good for me. It’s in a positive way, but they think it’s in a negative way. And I don’t think so.

Processes of Transformative Reading

Consider this scenario we observed. In the midst of a seventh-grade self-selected reading time, Marty interrupted the reading of the other students sitting in his cluster as he thought aloud, “Moron. Moron. Where’s the dictionary? I know what that word means but now I need to read the meaning.” He put down his copy of A Man Named Dave (Pelzer, 1999), found the entry for moron, and reported,

![]() The first definition is a person with a mental deficiency. There’s a second definition. This one says a stupid person. His mom calls him a moron. I know what that means, but now I’m thinking about what it really means.

The first definition is a person with a mental deficiency. There’s a second definition. This one says a stupid person. His mom calls him a moron. I know what that means, but now I’m thinking about what it really means.

Several of his classmates had read A Child Called It and its sequel, which was Marty’s current book, and others had only heard conversations about them. Regardless, they joined Marty’s thinking. Scott restated, “Like you call somebody a moron or a retard.” Patterson asked, “Wasn’t it enough that she smeared crap on his face?” to which Jason added, “. . . and made him eat it.” After a few seconds of silence, Scott lamented, “We call people that all the time,” and Marty responded, “When I read this definition, I’m thinking that’s not a good name to call anybody.”

Educators familiar with the work of Louise Rosenblatt might recognize this event as transactional (1983). In other words, reading does not simply involve a transfer of information from text to reader, nor is it merely an interaction where reader and text remained unchanged through the experience (Rosenblatt, 1985). They instead shape and are shaped by each other. In this instance, Marty had developed a relationship with Dave Pelzer in the social world of the memoir, and through the first- person narrative, also felt Dave’s pain and con-fusion. Consequently, he protested the words and actions of Dave’s mother. His social imagination— not only the competence to imagine the mind of another, but the propensity to do so— was extended to the author, and then, through conversation and self- reflection, to others outside of the text who might also be harmed by his own words. Evidence of the linkages between reading and social imagination has been widespread in our own work, but is also found in studies of young children (e.g., Lysaker & Miller, 2013). The consequential transformations in readers’ relational lives and social beliefs have also been found with adults (e.g., Bal, Butterman, & Bakker, 2011; Bal & Veltkamp, 2013; Busselle & Bilandzic, 2009; Mar & Oatley, 2008).

To take this a step further, though, consider the significance of Marty’s sharing with classmates. We have documented countless instances of students recruiting others to their reading (Ivey & Johnston, 2013) because they wanted friends, teachers, and parents to work through points of confusion with them, to offer their perspectives, or just to share the intensity of the experience. That intensity opens the conversations that produce other shifts, including participants revealing information about themselves, the expansion and deepening of relationships, and the development of trust. Within a trusting community, intermediate and middle grades readers do not have to negotiate on their own unsettling information they encounter, and in our experience, they are not inclined to do so. This should make us less nervous about children who are choosing to read more mature subject matter and, frankly, more realistic, because rest assured, others will be talking with them about what they read. But also important, the narrative is now shared by and is a part of the community because Marty felt compelled to talk about it. Several days later, it was Patterson, rather than Marty, who revived the conversation when he announced, “This is still bothering me.” He continued, “Why doesn’t [Dave Pelzer] say something about the abuse when he was still a kid?” His classmates took up the problem:

![]()

Charlie: Everything seems normal when you’re a kid.

Patterson: But why does his mother do that stuff to him?

Scott: It makes me mad at her.

Charlie: Maybe it was done to her when she was a kid.

Patterson: I still don’t know why people don’t know. Can’t they see the cuts?

Scott: Sometimes you carry the biggest scars on the inside.

Charlie: Can you report that stuff like after 10 years?

Notice that Patterson’s question is not answered explicitly, but instead, his classmates offer several possibilities. What becomes clear, through collaboration around a problem, is the realization that serious, vexing matters like this one and others they encounter in texts defy simple explanations. In other words, the multiple perspectives offered on the text make it less likely for children to accept what they read at face value. Also relevant are the expansion of the conversation and the blurring of lines between social worlds in and out of the book. Although we cannot be certain, we might infer that Charlie has some personal experience, or at least deeper knowledge about the topic, that complicates the conversation. We are struck by how Scott, in his second comment, appears to take up Charlie’s way of thinking about the issue.

Provocative Texts Taken Up in Community

To our knowledge, most conversations around mature narratives taken up by the middle school students we studied moved in a direction most adults would consider healthy and pro-social. But keep in mind that children’s thoughts and talk were undoubtedly influenced by the discursive environments of their classrooms. The way teachers invited students to think about books with complex issues was apparent in how they introduced new texts to the class, including their own recent reading. For instance, one teacher began telling about Dirty Little Secret (Omololu, 2010) by sharing that she had a close friend, like the main character of the book, whose mother was struggling with the problem of hoarding. She talked to students frankly about how difficult the problem had been for her friend’s entire family, and how the book helped her understand her friend’s dilemma in new ways. In other words, she resisted sensationalizing the subject matter, instead treating a real issue— and perhaps one that touched the lives of students in her class—with sensitivity. She also talked about the text as a tool for thinking and for enhancing her relationship to her friend, rather than as a form of entertainment.

Although most reading was selected by students, the books that teachers selected for students to think through together—with teachers reading aloud— were precisely those that inspired fervent conversations that placed some students at the edge of their comfort zones. Routinely popular throughout our time with students was Jumping Off Swings ( Knowles, 2009), which allowed students to confront the implications of casual sex, questions about abortion, and the consequences of decision making on selves and others. In the midst of a reading in one eighth-grade classroom, one student shared with her classmates her belief that she had been one of those consequences and wondered if her mother regretted the decision to have her. Up to that point, the perspective of an unwanted baby had been missing.

Rather than evade the issue or offer reassurances she could not be certain about, the teacher asked the class, “If you worried you had not been a planned baby, what are some different ways you could think about that?” In asking for a range of possibilities, the teacher resists the urge to give closure, and in doing so, she also invites students to dig deeper and to entertain multiple perspectives. This reduced need for closure, as facilitated by the teacher, is important, not only because it influences the way children will perceive and interact with each other (Kruglanski, Pierro, Mannetti, & De Grada, 2006), but it also shapes how children might perceive and interact with new information in texts without the teacher present, as we saw in our earlier example with Marty and his friends.

Throughout their reading of Jumping Off Swings, children had a continuous discussion about characters’ decisions, particularly related to the difficult realities of sex at a young age. Several months later, the teacher invited students to read a newspaper article about a fifteen-year-old boy who was sentenced to juvenile detention for rape, then released when his accuser recanted her accusation and confessed that the encounter was consensual. His latest dilemma, though, was that his name had already been indelibly entered on the sex offender registry. Reacting to that problem, the children’s teacher admitted, “When we were talking about Ellie and Josh (characters in Jumping Off Swings), I never even offered that up in my mind as a possible consequence of having sex so young.” Along with characters Ellie and Josh, this falsely accused young man was struggling to have his life restored, and he became an additional factor in the ongoing problematizing of the issues. Thus, the conversation continued— both within the community and within individual minds— and raised the likelihood that there were other perspectives not yet explored. For instance, future reading might include Orbiting Jupiter (Schmidt, 2015), the story (as told by his sixth- grade foster brother) of a 13- year-old father not only grieving the death of the child’s mother, but also unable to see his child.

We believe it is no coincidence that students participating in this sort of dialogic classroom might be similarly dialogic in their thinking and conversations around text in the absence of a teacher. An example from one of our studies (Ivey & Johnston, 2015, pp. 316– 317) illustrates this point.

When Akeem wanted several of his classmates to read and talk about Response (Volponi, 2009), he opened it to a section he knew would raise the ire of his friends and told them to read. As expected, Xavier and Terris almost immediately questioned the use of “n—-r” and other issues of racism they gleaned from that short section. Santino took it personally, saying if anyone called him a “b–ner,” he would “take a swing at them.” Xavier countered that instead, he “should be chill like Luis.” Luis was a character from Perfect Chemistry (Elkeles, 2009), a fact that needed no clarification, since this character and others populated the classroom discourse, and these boys frequently talked about characters’ dilemmas and used them as tools for their own lives. The intertextuality in this space involved the narratives students read, past and ongoing conversations, the narratives of their life histories and futures, and those of others, including characters. As such, these collective influences widened both the possibilities for other perspectives and the basis for choosing possible responses to life’s complications.

It is this uncertainty and the expectation of multiple perspectives that keep students engaged—with the texts, with each other, and with their own lives. Comfort with uncertainty— a reduced need for closure— is what alters the ways students view knowledge and each other. It allows them to see their own perspectives as real contributions to com-munity knowledge building, and, as a result, allows them to not be fearful of asking difficult questions. Thus, rather than view the lure of particular texts as problems for teaching, we suggest that within a discursive environment inviting dialogic response, these texts might be viewed instead as productive tools for learning. We now turn to some ways to arrange for such engagements

Supporting Emerging Adolescents

through Engaged Reading and Conversation

We owe a tremendous debt to the middle grades teachers and students from whom we have learned. Below, we expand on several guiding principles that we credit to them.

Centralize Engagement:

Engagement requires relevance, and because we do not know exactly what children will find relevant, we must make available a wide range of texts from which they can choose. Choice is important. Students have made it clear that in earlier grades, they would choose, on principle, not to read books they were required to read. Meaningful choice fulfills the human need for autonomy. However, it also builds initiative in reading. Children learn to choose to read and to find books they find worthy of their time.

When children are reading a range of books they find engaging (personally meaningful and a little challenging in one way or another), they find they have to talk with one another. It is through participating in or overhearing these conversations that students gather the information they need in order to choose books they will find engaging. Without the talk, students would only have book covers and impersonal publicity reviews and abstracts to inform their choices. For example, for half of his eighth-grade year, Reginald persisted in reading adventure books with animal characters, which had been his practice since about third grade. So when we saw Reginald deeply engaged in Twisted (Anderson, 2007), a book focused on adolescent relationships, we asked him about it. He said he did not know he would be interested in this kind of story until his classmate, Peyton, shared with him a portion of the text featuring the character’s inner dialogue—a battle between his brain and his hormones. Reginald recognized this tension and decided to read on his own.

In other words, engagement is not only with the books themselves, it is also with characters and with others around the books. Through engagement with each other, children begin to assume that there are multiple viewpoints on most issues and multiple sides to people and situations. A conversation about a character’s grief, deception, or insecurities, for instance, might become a space where children reveal, from their own experiences, alternative ways to think through unsettling behaviors— not just of characters, but also of each other and of unknown others. Teachers might not only expect, but also encourage such spontaneous talk. Without permission to talk, some students would lose their way in their reading, and thus, their engagement. When they encounter tough spots in their reading— interruptions in their comprehension— they turn to peers to help them sort out meaning.

Because students are often prohibited from talking during “silent” reading times, teachers might have to prompt appropriate conversation until it becomes the students’ new norm. Such conversations might stem from teachers’ own reading, with comments such as “I want to get your thinking on why this character is doing this . . .”; teachers could invite students to do the same by asking, “Is one of your characters bugging you?” or “Does anyone have a character in their story who needs our help?” We have observed several consequences of these simple actions, such as students scheduling time with each other to sort out a point of confusion in a book or spur- of- the- moment peer groups that include students who are reading a book, those who have finished, and those who have not read the book, but who know the story from listening to other conversations. In the classrooms we have studied, students choose their own books, but they do, in fact, read many of the same books, albeit at different times across the year. Thus, each time a new reader picks up a book, conversation ensues, and new angles on meaning are considered.

For teachers who need opportunities to develop some confidence around the idea of teaching in a class where students are reading a range of texts at once— as opposed to a whole class novel— reading a carefully selected text aloud to students is a good way to start building engagement. It allows teacher and students to share the experience and provides an excellent opportunity to make available narratives, characters, and genres students might not seek out on their own. For instance, a teacher who notices students are not reading books written by authors of color might choose a book by Jason Reynolds, Coe Booth, Kwame Alexander, or Malin Alegria.

Talk about Books as Tools:

We want children to find books and the conversations within and around them to be resources for making sense of the world— tools for building a self and thus relationships with others and the world.

We mentioned earlier a teacher who resisted sensationalizing a book in which a character struggled with hoarding and instead described it as useful for understanding a friend and her family. In our experiences, a good principle to apply when talking about and through narratives is to assume that someone in the class has been touched by difficulties similar to those faced by characters in the story. The point is not to avoid these issues, but to invite a different sort of conversation about them— one that focuses on hard decisions, emotions, and perspectives rather than character traits, plot dynamics, or what characters do, per se.

We might also consider linking narratives with each other across time as part of the same larger conversation. For instance, All American Boys (Reynolds & Kiely, 2015), a book that deals centrally with racism in communities, features the brutal beating of a blameless Black teen by a White police officer. It is told in the alternating perspectives of the victim and a White classmate— a friend of the police officer— who witnessed the incident. Significant to point out in introducing this book would be what we gain from being allowed to enter the minds of two different characters, and the fact that this book is the result of a collaboration between a Black author and a White author, adding another layer of potential mind reading. Kinda’ Like Brothers (Booth, 2014) is told from the perspective of an 11- year- old boy who resents his mother’s newest foster children— a baby and a boy close to his own age. Using All American Boys as a model, a teacher might suggest how useful it would be to imagine, while reading, the perspective of the older foster child as we learn more about his life.

Although it is true that students will use provocative tidbits or quotes from their books to draw in other readers and conversation partners, we notice that the dialogue quickly migrates to more substantial matters, and in fact, this is precisely what students have in mind. In one class, a student shocked her peers when she stated matter- of- factly that a character in her book had kicked another in her private region. There was an immediate response of gasps and some giggles, but there were also worried looks on some classmates’ faces. When one asked, “What would make her do that?” the reader was prepared and eager to talk about how the character’s anger was connected to complex and difficult family matters, and these issues were taken up further in conversation.

Asking why was a common practice in this classroom, no doubt shaped by the teacher. When this teacher talks about her own reading, you might hear her say, “I am reading this because I want to understand why a mother would leave her daughters alone for days with no food,” or “I want to understand why a person would stop eating.” Her response to characters engaging in self-destructive or anti-social behavior was not to judge or condone the activity, but rather to humanize it and try to understand it.

Open New Perspectives:

When students have questions and uncertainties stemming from reading and conversation, it might be tempting to provide answers or, if the subject matter is uncomfortable, change the subject. Neither option is usually best for developing sophisticated thinking or healthy dispositions toward unsettling information encountered in texts.

Earlier we referred to an incident involving nesting osprey and what appeared to be a murderous mother bird. Viewers were infuriated that no action was taken to save the babies. Taking a cue from the teacher who habitually asks why, we might seek out explanations for the mother bird’s behavior. Doing so would likely result in a range of possible theories, for instance, that it was an act of mercy. It would also lead to other stories of osprey parents who were fiercely protective of their offspring. We would not get answers, but instead we would further complicate our thinking and potentially motivate additional research. These complications keep the uncertainty and the conversation alive, but also underscore the realization that in order to know something, you have to explore it from many sides.

Just because engaged conversations typically emanate from students’ questions, and students play a large role in orchestrating these conversations, does not mean that teachers are unnecessary to the process. On the contrary, teachers are critical to facilitating the continuation of talk and nudging students beyond simplistic interpretations. Living Dead Girl (Scott, 2008) is a wildly popular book in the school communities we know that have it in circulation. Younger readers of this book often get stuck on the question of why an abducted, sexually abused girl would not make more substantial attempts at freedom. Noticing that students in her class were perseverating on this perplexity, yet not ready to leave it, a teacher found other books told from the perspective of teens held captive, including Stolen (Christopher, 2012), the memoir A Stolen Life (Dugard, 2012), and Pointe (Colbert, 2014), a narrative from the perspective of a friend of a kidnap victim. Students read and circulated the books enthusiastically. In the process, they became aware of a range of theories on why an abducted child might stay with his or her captor, including Stockholm syndrome, fear, and shame. Their question about Living Dead Girl was not answered, per se, but their minds were opened to the possibility that this problem defies simple answers, and they generated new questions, thus perpetuating the conversation. In the process, these children were expanding their ability to imagine others’ perspectives and the complexity of human emotions and motivations.

Development, Needs, and Cognitive,

Social, and Emotional Coherence

It is tempting to think of children in terms of developmental stages in which they are ready for this but not for that, or in which one stage is preparation for another stage. Although we are writing here with emerging adolescents in mind, even young children are encouraged to think about difficult issues of gender and equity and moral dilemmas that arise in engagements with narratives. Excellent examples can be found in books like Black Ants and Buddhists: Thinking Critically in the Primary Grades (Cowhey, 2006), Creating Critical Class-rooms: Reading and Writing with an Edge (Lewison, Leland, & Harste, 2014), Negotiating Critical Literacies in Classrooms (Comber & Simpson, 2001), and Getting beyond “I like the book”: Creating Space for Critical Literacy in K– 6 (Vasquez et al., 2003). Indeed, we hope that teachers of young children also find some relevance in the perspective we have offered here.

With adolescents, who often choose “disturbing” books, it can also be tempting to worry that they will take up the lives of flawed characters as models to live into. However, we have only seen this in a positive sense, as when Xavier suggested that rather than “take a swing” at someone for a racist comment, he “should be chill like Luis,” a book character. Making problematic choices about life narratives may be more likely when a child feels alienated from the community (Newman & New-man, 2001). Fortunately, we have found that within the conversations students have about books, they find that they need each other in order to know and be known. They recognize that they belong to a learning community and are competent members of it, a perception that could derail the likelihood of dysfunctional narratives.

Our work has taught us that although there are changes in the dilemmas of humanity that engage children over time, there are continuities in instructional principles. For example, in order to become engaged, children need a sense of personal relevance and a degree of uncertainty. Uncertainty is provoked by teachers, peers, and characters who open different perspectives, foreground moral dilemmas, and expose emotional and relational lives. We are not simply teaching children to read— though we are doing that. We are helping children to see books as tools for their own development. Only when they are fully engaged do they bring to bear the full coherence of their cognitive, emotional, and relational lives. In this context, their academic needs are met (they do better on tests) but so are their developmental needs (Ivey & Johnston, 2013).

Human beings need a sense of autonomy, competence, and belonging (Ryan & Deci, 2000). When everyone is required to read the same book, some students are less likely to have these needs fulfilled, and the potential for engagement is reduced. Differences in competence, narrowly defined, are fore-grounded, and some students have less to bring to the conversations than others. By contrast, when students choose to read different, personally relevant books, they at once gain a sense of autonomy and a sense of competence. The basis for simplistic comparisons is removed. Meaningfulness is fore-grounded, and each student brings something new and different to literate conversations; they become full participants in an engaged learning community.

Students also find a measure of success in other ways, for example, by persuading and/or helping others to read books that engaged them in order to solicit their opinions. These, in turn, bring a sense of belonging, and the conversations about charac-ters’ emotional and relational lives expand social- emotional and moral development along with self- regulation (Bernier, Carlson, & Whipple, 2010; Finkel et al., 2006). Fostering these engagements, processes, and connections is the heart of language arts teaching with children of all ages.

This article originally appeared in Language Arts, a publication of NCTE.

Gay Ivey is the William E. Moran Distinguished Professor in Literacy at the University of North Carolina Greensboro and a past president of the Literacy Research Association.

Peter Johnston is professor emeritus of literacy teaching and learning at the University at Albany.

.

Into the Classroom With ReadWriteThink

(powered by NCTE: National Council of Teachers of English)

Young adult literature has long been criticized for being too dark. It’s true that many YA authors choose to write about difficult topics. Violence, abuse, and trauma are never easy to stomach— in literature or in life. And yet if you talk to adults who actually work with teens, you soon learn that there are plenty of young people living the very situations we see depicted in YA lit. These teens deserve stories that tell the truth about their experience. So do teens whose lives are more sheltered. Literature can show us how ordinary people cope in the face of struggle and pain. In this podcast episode from ReadWriteThink.org, you’ll hear about teens who are dealing with a range of obstacles and hardships. http://bit.ly/1OINTDR

In this lesson plan from ReadWriteThink.org, students participate in learning clubs, a grouping system used to organize active learning events based on student- selected areas of interest. Guided by the teacher, students select content area topics and draw on multiple texts— including websites, printed material, video, and music— to investigate their topics. Students then have the opportunity to share their learning using similar media, such as learning blogs.http://bit.ly/2c6l1Tz

In this lesson plan from ReadWriteThink.org, students write to their school librarian requesting that a specific text be added to the school library collection. Students use persuasive writing skills as well as online tools to write letters stating their cases. Students then have an opportunity to share their letters with the librarian.http://bit.ly/1qGEodB

#banned books #benefits of the humanities #Literacy #benefits of reading

Endnotes:

[1] Gay Ivey and Peter Johnston. “What Happens When Young People Actually read ‘Disturbing’ Books.” Teachers College Press blog. October 31, 2023.

[2] Gay Ivey and Peter Johnston. “What Happens When Young People Actually read ‘Disturbing’ Books.” Teachers College Press blog. October 31, 2023.

[3] Gay Ivey and Peter Johnston. “What Happens When Young People Actually read ‘Disturbing’ Books.” Teachers College Press blog. October 31, 2023.

[4] Gay Ivey and Peter Johnston. “What Happens When Young People Actually read ‘Disturbing’ Books.” Teachers College Press blog. October 31, 2023.

[5] 2023 Voice of the Superintendent. EAB (formerly Education Advisory Board).

References:

Bal, P. M, Butterman, O. S., & Bakker, A. B. (2011). The influence of fictional narrative experience on work outcomes: A conceptual analysis and research model. Review of General Psychology, 15, 361– 370.

Bal, P. M., & Veltkamp, M. (2013). How does fiction reading influence empathy? An experimental investigation on the role of emotional transportation. PLoS ONE, 8(1), e55341. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0055341

Bernier, A., Carlson, S. M., & Whipple, N. (2010). From external regulation to self- regulation: Early parenting precursors of young children’s executive functioning. Child Development, 81, 326– 339.

Busselle, R., & Bilandzic, H. (2009). Measuring narrative engagement. Media Psychology, 12, 321– 347. doi: 10.1080/15213260903287259

Comber, B., & Simpson, A. (Eds.). (2001). Negotiating critical literacies in classrooms. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Cowhey, M. (2006). Black ants and Buddhists: Thinking critically and teaching differently in the primary grades. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Finkel, E. J., Campbell, W. K., Brunell, A. B., Dalton, A. N., Scarbeck, S. J., & Chartrand, T. L. (2006). High- maintenance interaction: Inefficient social coordination impairs self- regulation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91, 456– 475.

Guthrie, J. T., Wigfield, A., & You, W. (2012). Instructional contexts for engagement and achievement in reading. In S. Christenson, C. Wylie, & A. Reschly (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Student Engagement (pp. 601– 634 ). New York, NY: Springer.

Ivey, G. (1999). A multicase study in the middle school: Complexities among young adolescent readers. Reading Research Quarterly, 34, 172– 192.

Ivey, G., & Johnston, P. H. (2013). Engagement with young adult literature: Outcomes and processes. Reading Research Quarterly, 48, 255– 275.

Ivey, G., & Johnston, P. H. (2015). Engaged reading as a collaborative transformative practice. Journal of Literacy Research, 47, 297– 327.

Kruglanski, A. W., Pierro, A., Mannetti, L., & De Grada, E. (2006). Groups as epistemic providers: Need for closure and the unfolding of group- centrism. Psychological Review, 113, 84– 100.

Lewison, M., Leland, C., & Harste, J. C. (2014). Creating critical classrooms: Reading and writing with an edge. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis.

Lysaker, J. T., & Miller, A. (2013). Engaging social imagination: The developmental work of wordless book reading. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 13, 147– 174.

Mar, R. A., & Oatley, K. (2008). The function of fiction is the abstraction and simulation of social experience. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3, 173– 192.

Newman, B. M., & Newman, P. R. (2001). Group identity and alienation: Giving the we its due. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 30, 515– 538.

Rosenblatt, L. (1983). Literature as exploration. New York, NY: The Modern Language Association of America.

Rosenblatt, L. (1985). Viewpoints: Transaction versus interaction: A terminological rescue operation. Research in the Teaching of English, 19, 96– 107.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self- determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well- being. American Psychologist, 55, 68– 78.

Vasquez, V., Muise, M. R., Adamson, S. C., Heffernan, L., Chiola- Nakai, D., & Shear, J. (2003). Getting beyond “I like the book”: Creating space for critical literacy in K– 6 classrooms. Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Children’s and Adolescent Literature Cited:

Anderson, L. H. (2007). Twisted. New York, NY: Penguin.

Booth, C. (2014). Kinda like brothers. New York, NY: Scholastic.

Christopher, L. (2012). Stolen. New York, NY: Chickenhouse.

Colbert, B. (2014). Pointe. New York, NY: Penguin.

Dugard, J. (2012). A stolen life: A memoir. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Elkeles, S. (2009). Perfect chemistry. New York, NY: Walker.

Hopkins, E. (2004). Crank. New York, NY: Margaret K. McElderry.

Hopkins, E. (2006). Burned. New York, NY: Margaret K. McElderry.

Hopkins, E. (2008). Identical. New York, NY: Margaret K. McElderry.

Knowles, J. (2009). Jumping off swings. Somerville, MA: Candlewick.

Omololu, C. J. (2010). Dirty little secrets. New York, NY: Walker.

Pelzer, D. (1995). A child called It. Deerfield Beach, FL: Health Communications.

Pelzer, D. (1999). A man named Dave. New York, NY: Dutton.

Reynolds, J., & Kiely, B. (2015). All American boys. New York, NY: Atheneum.

Schmidt, G. D. (2015). Orbiting Jupiter. New York, NY: Clarion.

Schroeder, L. (2009). Far from you. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Scott, E. (2008). Living dead girl. New York, NY: Simon Pulse.

Shakur, T. (1999). The rose that grew from concrete. New York, NY: MTV Books

Sitomer, A. L. (2008). Homeboyz. New York, NY: Hyperion.

Volponi, P. (2009). Response. New York, NY: Penguin.

Images:

What Actually Happens When Young People Read Disturbing Books:

Photo by Vladislav Anchuk on Unsplash

Children’s Views on Learning from Narratives: Photo by Johnny McClung on Unsplash

Processes of Transformative Reading: Photo by Thought Catalog on Unsplash

Provocative Texts Taken Up in Community: Photo by javier trueba on Unsplash

Supporting Emerging Adolescents Through Engaged Reading and Conversation:

Photo by Armando Arauz on Unsplash

Development, Needs, and Cognitive, Social & Emotional Coherence:

Photo by Hannah Busing on Unsplash

he Giver is about Jonas, an eleven-year-old boy who lives in a futuristic society where life appears to be nothing less than idyllic. If everything in this world is so perfect, what‘s the rub? Why was The Giver

he Giver is about Jonas, an eleven-year-old boy who lives in a futuristic society where life appears to be nothing less than idyllic. If everything in this world is so perfect, what‘s the rub? Why was The Giver

Albert Einstein is literally the face of the STEM education so highly regarded in society today. We see his likeness on countless numbers of brochures for science programs, camps, and fairs. But, what did Einstein himself say about education? A lot of us would be shocked to discover that he championed a

Albert Einstein is literally the face of the STEM education so highly regarded in society today. We see his likeness on countless numbers of brochures for science programs, camps, and fairs. But, what did Einstein himself say about education? A lot of us would be shocked to discover that he championed a

hy are books written, if not for a reader’s enjoyment? People have been telling stories since the dawn of time. As Ursula K. Le Guin points out, “There have been great societies that did not use the wheel, but there have been no societies that did not tell stories.”

hy are books written, if not for a reader’s enjoyment? People have been telling stories since the dawn of time. As Ursula K. Le Guin points out, “There have been great societies that did not use the wheel, but there have been no societies that did not tell stories.”