Reclaiming Claims: What English Students Want from English Profs

.

“So you like therapy, eh?”

I was in the Jellema Room, an intimidating chamber of dusty philosophical tracts, stale coffee, slow e-mail, and a coterie of would-be philosophers. As a philosophy major, I had earned the right to enter; as an English major, my presence had been challenged.

“What do you mean, therapy?”

“Isn’t that all you do in English classes?” my friend quipped. The coterie laughed. “You come to class and the teacher says, ‘OK, kiddies, what did you think of that? Did you liiiike that? How did it make you feeeel?’ ” He was on a roll.

I’m sure, in his self-amusement, my friend considered himself rather witty and original; in reality, his view of English fit neatly into a tradition of suspicion that fills the various halls and chambers of the academy as if gassed through the ventilation system: “Everyone knows,” as Andrew Delbanco (1999: 32), an English professor himself, writes, “that if you want to locate the laughingstock on your local campus these days, your best bet is to stop by the English department.” “After all,” my friend wound up his spiel, “that’s why so many people take English. It’s easy. It isn’t real.”

But the sentiment, it would seem, is not confined to the academy. Unless your parents happen to be English professors, telling them that you’ve settled on an English major can be a rather unsettling affair—ranging anywhere from nerve-racking to family-splitting. (One friend I know who decided on a Great Books program at a major university had such a falling out with his father that they haven’t spoken in two years.) Nor has it been easy since graduation to justify the decision I have made. Seeing old faces or being introduced to new ones, now with a degree in hand, I am continually asked the same question: “And what do you do now?”

At first, I began by answering with the truth: that I’m working a few part-time jobs, waiting on grad school, and trying to write. The reactions, I began to notice, could be classified Aristotelian style into two species: horror and romance. The first is by far the more common: Feigning a smile, the entrepreneuring-investment-banking-Lexus-driving-twenty-eight-year-old- lawyer thanks what deities she believes in that English never enticed her, says “Ohhh” rather awkwardly, and excuses herself to use the restroom. The other, the romantic, thinks I’m living in a cardboard box among the poor and outcast, writing words that will outlive our mortal, feeble flesh, changing lives in a future none of us will see. These, apparently, are the only two responses available for non–English majors attempting to understand what exactly I’m doing with my life.

Recently, I went through the same ordeal in meeting the family of a new friend. The father—a banker, of course—was lounging in a plush recliner behind his copy of Forbes magazine as the Asian Market Watch rambled on above a rush of stock quotes skimming across the screen. “And writing,” I said. He looked up. “Fake stuff or real?” I blinked, my mouth opened slightly in the universal expression of incomprehension. “I mean, are you writing fiction or non?” Now, I’m not so careful a judge of character as, say, Sherlock Holmes, Columbo, or the lady from Murder She Wrote, but I’m pretty sure that my questioner was not joking. Fiction, apparently, was fake.

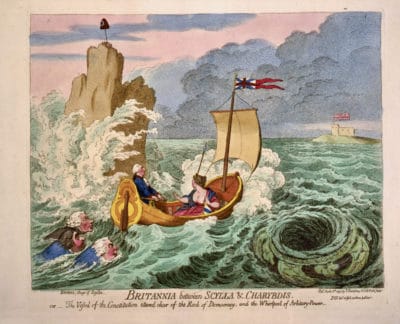

Inside and outside the academy, the English professor and the English pupil run into a common problem: the rest of the world thinks what we do and what we study is fake. English ranges anywhere from “entertainment” to “therapy,” but it seldom enters the realm of the real—the “real,” I suppose, meaning a productive contribution to society yielding tangible, green results.

Thus the “So what?” of English rattles in the back of our minds like an empty can attached to an exhaust pipe. Why read fiction? Why spend one’s life teaching it? As another acquaintance once asked me, “What’s the point?” Some teachers deal with the question by ignoring it. A few might answer in strictly utilitarian terms: it pays the bills. Most, however, probably believe that literature has something important to impart—and it’s that importance, that something, that keeps them in the business. As Italo Calvino (1993: 1) writes, “My confidence in the future of literature consists in the knowledge that there are things that only literature can give us, by means particular to it.” What are those things?

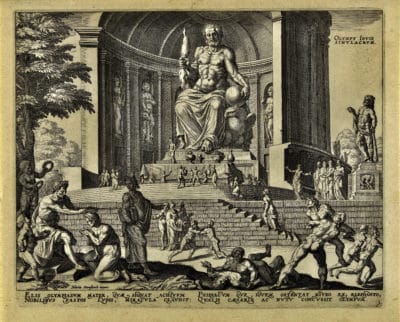

Back in the late fourth century, a lusty intellectual pondering his state of affairs to the point of great distress happened to hear a child chanting, “Pick up and read. Pick up and read.” Augustine, figuring it a divine command (as he was wont to do), picked up a Bible, read Romans 13, and found the experience somewhat refreshing (“it was as if a light of relief from all anxiety flooded into my heart” [VIII.29]). Next thing you know, he converted to Christianity, became a bishop, and was posthumously proclaimed a Doctor of the Church. The point is not to suggest that reading the Bible (or any other piece of literature) will necessarily make converts of us all. Rather, I mean to suggest that conversion, whether to Christ or to Camus, is held forth in every text as a distinct possibility—that is, that literature can act as the undiscovered fifth element, the alchemist’s stone offering those who touch it the possibility of leaving changed.

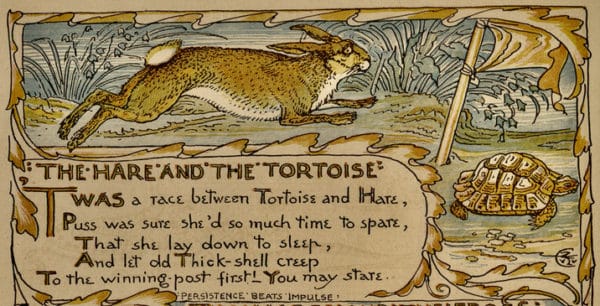

Moreover, I would argue, it is the possibility that literature can change us that draws most students in to hear it speak.[1] Many students—those not disillusioned by bad teachers—come to literature with a kind of brimming anticipation, waiting for what will appear. Another Augustine, one a bit more contemporary, illustrates such anticipation beautifully. Augustine (Gus) Orviston, the narrator of The River Why, is an angler so obsessed with fishing that he’s hardly read a book in the first twenty years of his life. When a tutor, Titus, finally convinces him to start reading, this is what occurs:

Scholar though he was, Titus was no academician: accuracy and intricacy of knowledge were to him not just secondary but twentysecondary to the love one felt for the things one studied, so whenever I was unable to love a book, even if I wanted to struggle with it, Titus whisked it away and proffered another. And when I challenged him on this he explained that philo meant “love” and Sophia meant “wisdom,” that every book he gave me was full of wisdom, but that in order for my reading of them to be truly philo-sophic I must not just read but love them. It seemed to work: at least I soon found myself eyeing the covers of unknown books with the same sense of expectancy I felt when scrutinizing the waters of a new stream. (Duncan 2002: 200–201)

Some might object at first to Titus’s whisking books away, offering sound arguments for the good of struggle despite a lack of pleasure. Of course, the objectors would be right: abandoning the struggle is no way to progress properly. But I read in this passage something far more fundamental occurring. Titus is teaching Gus to read, and the first part of reading is loving literature, and the greatest part of loving literature is approaching it with expectancy. It is that expectancy most English majors possess—an expectancy that something of substance will rise from the pages, and in catching it, the students themselves will be caught.

Still, say others, Gus is reading philosophy, not literature. Granted that the distinction between the two is often about as clear as the difference between Scottish and Irish accents to the ears of a Chinese farmer, the objectors are basically right: Gus reads nonfiction. Two responses should be made. First, Gus’s allusions to works of literature throughout The River Why (together with the fact that it’s a story he chooses to write) reveal a reading list filled with at least as much literature as philosophy.[2] Gus’s “philosophizing” is broader than the borders of the academic discipline called philosophy. But second, the manner of reading Gus is learning in this passage has nothing specific to do with philosophy. To put it in a way that sounds almost stupid in this context, Gus is discovering precisely what lovers of literature have always known: that literature is important.

Pick yourself up off the floor. Let us continue.

It is not just that literature is important; it is that the importance of literature is precisely what students of English take English to experience—a subtler point seemingly lost on many academics. Students do not take literature to learn only what constitutes a metaphor or a simile; they take literature because metaphors and similes say something. In other words, the answer to the question “What do students of literature want a literature class to teach?” is the same answer that ought to have put professors in the business to begin with: that it matters for their lives.

I remember my first day of English 311. I was a sophomore bent on a philosophy degree, fulfilling my literature requirement by taking a professor I had heard was a decent guy. When the clock struck 9:00, a tall, middle-aged man with a gray beard strode into class, his dark green sweater swinging down above his black pants and brown shoes. It was the day affectionately known as “Syllabus Day,” the do-nothing day, the day when the most important event of each class was figuring out whom you knew and where to sit. Our professor did not care where we sat. He plopped down his heavy Norton anthology on the front podium and turned around.

“What are you doing here?” he asked. We gazed up at him, a bit shocked. Some students had just rolled out of bed, and their greasy hair still stood on end. “Why are you in college?” he asked. “What are you in this English class for?” The questions came at us like bullets fired from a twelve-gauge shotgun. These were not the questions of Syllabus Day that we had come to know and love; we were not prepared to defend our purposes in life.

But the professor did not wait for any answers (good move). Instead, he began to run through a long list of statistics and quotations pointing to a culture sinking into mindlessness, into an inability to reflect and to question, into an incapacity to even consider the existence of a good life and a bad life, let alone know the difference between the two. He concluded: “The world is in need of people who can think. Let what you read this semester be the beginning of your thoughts, and above all things, let the stories you run across run across you. Saul Bellow once said, ‘The worst thing you can omit from your studies is yourself.’ These stories are all, in some way, yours.”

I realize teaching is not necessarily about giving students what they want—that might amount to little more than free pizza. Still, a student’s desires are not entirely insignificant, particularly those desires students didn’t know they had. Good teachers have a way of eliciting those deep passions that students are either too embarrassed or too busy or too distracted to realize they possess. One of those deep passions is a desire for substance, for some weight other than a letter grade to hang on what we do, for some importance attached to our hours of study beyond a possible degree, career, house, family, and life of flat success. Sure, the numbers tell us that college is financially a good investment; but most eighteen-year-olds I’ve met are not interested in financial investments. They’re far more interested in understanding the world in which they live and determining for themselves whether it’s worth an investment of their lives.

Students, in other words, are ardent creatures—a claim that may surprise many professors who have noted only the drooping eyelids, the late papers, and the characteristic smirk or shrug of the shoulders that “proves” another case of apathy. Often, however, apathy is merely latent ardency, a desire for substance possessed without knowledge of the possession, a caring that relies on others to draw it out. The more professors treat students as if they do care—and as if they should—the more they will discover students who actually do. Latent ardency depends on the overt ardency of others to sneak out of its shell and take a look around.

Examine, for example, the case of Dorothea Brooke in George Eliot’s Middlemarch.

The intensity of her religious disposition . . . was but one aspect of a nature altogether ardent, theoretic, and intellectually consequent: and with such a nature, struggling in the bands of a narrow teaching, hemmed in by a social life which seemed nothing but a labyrinth of petty courses, a walled-in maze of small paths that led now whither, the outcome was sure to strike others as at once exaggeration and inconsistency. The thing which seemed to her best, she wanted to justify by the completest knowledge; and not to live in a pretended admission of rules which were never acted on. Into this soul-hunger as yet all her youthful passion was poured; the union which attracted her was one that would deliver her from her girlish subjection to her own ignorance, and give her the freedom of voluntary submission to a guide who would take her along the grandest path. (2000: 24–25)

Her desire for Mr. Casaubon, an old and ugly but intellectually eminent man, can be described as a desire for substance. Explaining the possibility of marriage to her sister, she says, “I should know what to do, when I got older: I should see how it was possible to lead a grand life here—now—in England” (25). The point is not that Dorothea is exceptional in her desires, but that she is quite normal. Many students find themselves full of “soul-hunger,” of a “youthful passion,” of an ardent desire to be told that the stories they are in the process of living somehow matter to the wider world in which they’re lived. Literature, with its array of stories, has the possibility of showing these students both how their lives matter and how to make them matter—a point I will illustrate soon.

But first, Dorothea has a sister, Celia, who cannot be ignored. Whereas Dorothea is full of passion to escape the constrained ignorance of her social norms, Celia is all too prepared to accept them. Her life is fulfilled not by large projects of social justice, but by marriage to the right person and a perfect-looking child. She does not have the “soul-hunger” that characterizes her sister and leads to her sister’s struggles. Though many students identify with Dorothea (and many would, if they could be shown that the source of their restlessness is a desire for substance), many others identify with Celia.

A classroom, therefore, is filled with both Dorotheas and Celias. The problem is that they cannot be sorted out. Many teachers, it would seem, notice the way a certain student dresses, or slouches, or writes, or whatever else, and assume they have the student pinned. If the professor then teaches literature as though the student does not care, the result will be a student who fulfills the professor’s expectations: she will not care a whit. What students of English want from their professors is the opening assumption that everyone is Dorothea, that everyone might care if they were shown a reason to—and the literature they are about to read might actually be the means to open them precisely to that possibility.

In Middlemarch we are given the opposite scenario. Mr. Casaubon, after marrying Dorothea, treats her as if she were Celia. As a result, Dorothea withers. Her life whittles away, lightened and expanded only when—occasionally—she finds reprieve from the clutches of her husband. Of Mr. Casaubon, Eliot writes: “There is hardly any contact more depressing to a young ardent creature than that of a mind in which years full of knowledge seem to have issued in a blank absence of interest or sympathy” (188). Her casual remark concerning the old man echoes down to teachers as a proclamation and a prediction. Unfortunately, many seem to have substituted knowledge for passion, filling themselves with facts they fire off above the heads of students, who in turn stare blankly through the windows in the room.

When my professor in English 311 finished firing directly at us in his opening day salvo, I looked over to find tears in the eyes of a friend. Corny, I know; almost unreal. Yet there it is. It happened. This guy—middle-aged, gray-bearded, dressed as only professors dress—strolls into class and tells us all to think, tells us literature can begin our thoughts, tells us, in essence, that our lives are implicated in the lives we read about, and that both, ultimately matter. It’s all my friend had needed to hear.

Which is not to conclude that that is all a teacher has to say. And here, the subject grows a bit trickier. For if we grant a (latent) desire in students to hear that the literature in which they are engrossed matters for the lives they live, we still have not established what a teacher is supposed to teach. How does a teacher mediate between a text and the (ardent) student who reads it?

Perhaps we should begin with what it seems is being taught. The answer, it seems to me, is some form of New Criticism—the text as a detached, lifeless body, lending itself to all sorts of interesting autopsies but never quite raising a finger to resist the scalpel at its chest. The reasons for New Criticism’s dominance in pedagogy (despite its decline in theory) are beyond the scope of this essay (and largely beyond the scope of my knowledge). Perhaps it amounts to little more than a lack of alternatives. Many schools of criticism and theory have arisen, but most have been too ideologically narrow to be adopted as a general pedagogical method (e.g., Marxism, feminism, and the like). Deconstruction, on the other hand, makes more universal claims concerning language but ends ultimately in a hopeless play of signifiers that yields little substance for a professor attempting to teach. Suffice it to say, as David Richter (1998: 708) writes, that “even today the critical practice of many American teachers of literature owes a great deal to Cleanth Brooks and William Empson.”

Thus we come to the crux of the problem. Texts, as taught, have lost the life that led students into English classes to begin with. How, then, without resorting to gushy, therapeutic questions of “feeeeling,” do teachers reattach a text and its significance to the lives of those who read it? How can literature matter enough to transform its students?

First and foremost, claiming that literature matters assumes that literature makes claims. It would appear, from my amateur observations, that philosophy is still considered a legitimate discipline because it’s in the business of sorting out truth-claims—universal statements made to change the way someone approaches any number of a range of subjects. Literature, on the other hand, has lost its claim to claims. As Robert Scholes writes in The Rise and Fall of Literature, “We are in trouble precisely because we have allowed ourselves to be persuaded that we cannot make truth claims but must go on ‘professing’ just the same” (qtd. in Delbanco 1999: 35). That need not be the case. Texts make claims whether professors explicate them or not, and it is the manner in which texts make them that reveals a bridge whereby the life of the text and the life of the reader may touch.

Yet the claims of literature differ vastly in form from the claims of philosophy. Where philosophy attempts to be explicit and clear (especially in the Anglo-Analytic arena), literature approaches through the indirect. Emily Dickinson (1963: 792) advised,

Tell all the truth,

but tell it slant.

Success in circuit lies.

It would seem that novelists listened. As Walker Percy (1991b: 304) notes, “Novelists are . . . disinclined to say anything straight out . . . since their stock-in-trade is indirection, if not guile, coming at things and people from the side so to speak, especially the blind side, the better to get at them.” That indirection comes through the construction of a world where claims dominate as natural laws. In other words, instead of using symbolic logic to elucidate truth-claims in the world, fiction uses symbols to intimate truth-claims within a worldview. The claim of each work is the guiding perception, the whole work as a whole claim, unparaphraseable, universal, and philosophically applicable to the world in which the reader lives. In essence, each text says to the reader, “This is the way things are,” and (occasionally), “This is the way things ought to be.”

Perhaps an illustration may help. Understanding the claim of a text involves entering the textual world where that claim dominates by natural law. In John Webster’s The Duchess of Malfi, for example, the natural law seems to be tragedy beyond the reach of hope as each character flickers out of existence like a candle caught by the wind. The world is a place where redemption does not exist. Darkness descends immediately as the house- lights dim and continues until the final curtain falls and the stage lights are blacked out. Good and bad alike are indiscriminately destroyed. As Antonio lies dying he utters these words, reflective of the play:

In all our Quest of Greatnes . . .

(Like wanton Boyes, whose pastime is their care)

We follow after bubbles, blowne in th’ayre.

Pleasure of life, what is ’t? onely the good houres

Of an Ague: meerely a preparative to rest,

To endure vexation. (1927: 120)

The quote is not meant to state the “claim” of The Duchess of Malfi, for the claim of The Duchess of Malfi is simply The Duchess of Malfi itself—its world as a presentation of the world. Yet Antonio’s words seem to let us in on the guiding natural law: The Duchess of Malfi presents a reality dominated by reckless cruelty—one in which individual lives are doomed to fade away and disappear. Thus the dying Bosolo reflects on the imminent death of the Cardinal lying beside him:

I do glory

That thou, which stood’st like a huge Piramid

Begun upon a large, and ample base,

Shalt end in a little point, a kind of nothing. (123)

As the Cardinal goes, so shall all others: ambition and nobility alike erased. The piled bodies in the final scene represent the inescapable law’s natural progression—a progression that leaves nothing to do but “make noble use / Of this great ruine” (124). Yet on the basis of this play alone, even that “noble use” seems doomed to fail. Tragic failure, inescapable and hopeless, descending on the good and bad alike, making useless human ambition and human nobility—this is the worldview of The Duchess of Malfi. To fully grasp that worldview, along with its concomitant views of human nature, one has to engage the entire drama, with all of its characters and all of its results. All paraphrases will in some way cheat the worldview they attempt to describe.

The important point in all this, however, is that the worldview of The Duchess of Malfi is the basis for a claim that extends beyond the borders of the drama, for the play’s claim is nothing less than an extension of its worldview into the world of its reader.[3] The Duchess of Malfi, like all literature, is proclaiming that its reality is reality. The bleak end is a prediction for the world of the spectator as much as an occurrence on the stage. The world of the text and the world of the reader overlap, and only in that overlapping does literature gain its significance, its possibility of effecting any change, its chance to speak to the one who reads. The Duchess of Malfi says, in effect, “These are the laws that govern our lives,” and in the end, it raises the crucial question for the student who engages with it: “Are these really the laws that govern my life?”

What this reattachment of textual worlds and textual claims requires of professors is a method distinguishable from New Criticism more in its ends than in its means. That is, instead of teaching The Duchess of Malfi as something strictly autonomous—examining its structures, wordplay, and the like in a system closed off from both the author and the reader—professors would teach The Duchess of Malfi as a world dominated by claims: that is, explorations of the text act as explorations of claims to which the reader must respond. To ask, “Can characters really change within this story?” is also to ask, “Can human beings really change?” To ask whether grace is available within the story is to ask whether grace is available to us. Each story, as a claim, declares that the reality of its characters is the reality of its readers.[4]

If texts are treated as realities meant to interpret the reality of their readers, then literary tools become absolutely indispensable. Students must know what a metaphor is, what a simile is, what rules govern various genres, and the like. A strictly therapeutic classroom—asking students only how they felt while reading or whether they liked what they read—does less to connect students to the text than teaching the intricate constructions that undergird it. Therapy-based English classes answer students knocking at the door not by opening it, but by asking them how they liked knocking: how did it make them feel? The more a student understands language and how it works, the more a student will be able to enter the literature that is read. The difference, however, is that what defined the telos for New Critics is changed into a means that serves another end. In other words, the typical disillusionment of students in literature classes could be countered by showing them that the “dry, boring, scholarly” activity of the English discipline is intimately linked to literature’s transformative powers. Understanding the claims made by a text (including the debate concerning what those claims actually are) relies upon the use of textual tools.

Consider, for example, “Nausicaa,” the thirteenth chapter of James Joyce’s Ulysses. One can read the chapter without any knowledge of genre. But understanding genre transforms the chapter and the claims that the chapter makes. Throughout, Joyce employs the language of a cheap romance novel to undercut such romance and reveal its inherent violence. He writes, for example, “She would fain have cried to him chokingly, held out her snowy slender arms to him to come, to feel his lips laid on her white brow, the cry of a young girl’s love, a little strangled cry, wrung from her, that cry that has rung through the ages” (1986: 300). The irony, of course, is that Leopold Bloom is voyeuristically gazing at a woman on the beach, so that the love they eventually make is nothing but masturbation, self-pleasure at the expense of another.[5] When the woman rises, Bloom notes with horror, “She’s lame! O! . . . Glad I didn’t know it when she was on show” (301). The limp bespeaks a violence, and the scene dashes notions of love established in romance novels through use of the very same genre. Understanding the literary genre is absolutely crucial to understanding the claim being made. A teacher connects the dots—connects the genre to the undercutting of the genre and finally to the claims made concerning love, violence, and voyeurism. Students are free to disagree with the final analysis, but such a final analysis will seldom even be reached without a teacher to guide. Those who lack the insight that a teacher can offer will see in this text little more than a pornographic scene.[6]

In the same way, new insights are discovered and new meanings encountered with the accumulated knowledge of each literary device. Such knowledge expands perception, so that the same text that once ran across a student’s mind like a river over rocks begins to seep in like rain into the soil. Some students bring their own ardency—their own “soul-hunger”—to the literature they read, some discover a dormant ardency awakened by their professor, but almost all students require the guidance and the knowledge a teacher offers to fill the hunger that they bring, to not only delight in literature but also to find in it the possibility of utter transformation—the possibility, each time, of conversion.

Such substantive reading leads to substantive reflection. In the same English 311 class where we were told to think as if for the first time, we read early twentieth-century American literature. Early twentieth-century American literature is nearly enough to cause a suicide or two. Prozac ought to be distributed as freely as hard candy to students subjected for a semester to the full brunt of naturalism. And yet, even naturalism, in all its doom—I always envision a foot slowly descending heel to toe on a helpless individual—could not annihilate a certain student’s sense that lives might matter, her life in particular. At one point, discussing the William Dean Howells story “Editha,” this classmate asked our professor a cutting question: “Why,” she asked, “did these naturalists bother to write? Writing itself seems to me a sign of hope. Editha, even if she is crushed, matters to me now where she never would have had no one bothered to write. Maybe because of Editha, I won’t end up an Editha myself.” Did the naturalists, though dooming, still hope despite it all? Regardless of how much or how little they thought human lives might matter, their fiction evoked a sense of worth decades after the authors were deceased. And this much I can affirm: that question would never have come if our teacher, from the start, had not thought the literature we were reading was making claims upon our lives.

To conclude, let me digress. Each year at the University of Chicago, incoming freshmen experience a sixty-minute oration titled “The Aims of Education”—an experience most of them probably consider an ordeal rather than an opportunity. In 2002, Andrew Abbott, a professor of sociology, spoke. After successfully annihilating any claim to the instrumental uses of education, he defined education as “the ability to make more and more complex, more and more profound and extensive, the meanings that we attach to events and phenomena” (2002: 7). As such, education is “the emergence of the habit of looking for new meanings, of seeking out new connections, of investing experience with complexity or extension that makes it richer and longer, even though it remains anchored in some local bit of both social space and social time” (7). In other words (and in the realm of English), education means the ability to read the same passage as one once did uneducated and find in it more implications for one’s life; it means the ability to bring more of one’s life to bear on more of one’s text, though reading the actual words takes no longer than it ever did; it means expanding experience, broadening it so that literature has the space to settle in; it means not only wanting to be transformed each time one reads, but being able to open oneself to such conversion. And the teacher that teaches this—not to dissect a text, but instead to cut its readers open—will teach students what they most wanted to learn: how literature matters for their lives.

In the end, students enter English classes because they believe that English matters, that it has something to say, and that, ultimately, their lives are implicated in and affected by what is said. This ardency (however latent) cannot be squelched by teachers who never attach texts and their claims to students and their lives. No author ever wrote who had nothing to say, and no text, however distant from its author’s intention, is silent. Students seek professors of English to be taught how to listen, how to hear with open ears the literature that they read. What brings many students to English classes is a substance greater than the weight of any grade and too important to be treated as a set of pedantic rules or an ungoverned territory of free and meaningless play; it is a substance that inspires the words of texts—that is, that breathes life into them—so that texts sit up and point their fingers at the lives of the students who read them, demanding a response. That is the substance that students seek; good teachers reveal how it is found.

Essayist bio:

Abram C. Van Engen is associate professor of English at Washington University in St. Louis, where he is also associate professor (by courtesy) at the John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics. Professor Van Engen has published widely on religion and literature, focusing especially on seventeenth-century Puritans and the way they have been remembered and remade in American culture. Books include: City on a Hill: A History of American Exceptionalism,Sympathetic Puritans: Calvinist Fellow Feeling in Early New England,A History of American Puritan Literature, as well as Feeling Godly: Religious Affections and Christian Contact in Early North America.

Photo credit: Joe Angeles/WUSTL Photos

Please note: This essay first appeared in

Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature,

Language, Composition, and Culture

(Volume 5, Issue 1, Winter 2005).

Pair with This Book is Banned’s section on The Art of Reading.

#literary criticism #the art of reading #liberal arts #benefits of Humanities #critical thinking

.

Endnotes:

[1] Sir Philip Sidney laid out three goods of literature: it teaches, delights, and moves. In this essay, I do not mean to deny the power of delight in attracting readers to texts and students to English classes. After all, as Walker Percy (1991a: 246) says, “When all is said and done, a novel is only a story, and, unlike pathology, a story is supposed first, last, and always to give pleasure to the reader.” At the same time, I believe it is the possibility of changing readers (a mixture of both teaching and moving) that draws most students—wherein I understand students to be a group of people roughly between the ages of eighteen and twenty-two, unsure what exactly life has in store for them or they for it, and so existing in a state of (relative) openness, sorting out plausible reasons to move in one direction or another.

[2] So, for example, describing two boys wrestling with him only two pages later, he writes, they “disdained deodorant, and delighted in mashing my face into their armpits for the sheer Walt Whitmanesque celebration of it, and . . . roared extempore Songs of Their Selfs afterward, gloating over how much older and taller I was” (2002: 203).

[3] One is free to disagree with my interpretation of The Duchess of Malfi and its worldview, but in so doing, the debate will have been begun as to the claims of The Duchess of Malfi. I do not mean to imply that one will be right and the other will be wrong, as if texts had only one claim to make and once it was discovered the text itself could be shucked. A text exhibits many claims cast by its overarching worldview—a worldview that itself is open to debate. What I am attempting to maintain, however, is the attachment between debates concerning the text itself and the claims that the text makes upon its readers.

[4] Notice, please, that I am not suggesting that professors answer such questions on behalf of their students, or use literature as a set of didactic tracts to teach students how to live the life a certain professor considers best. Questions must be raised within the bounds of the text; let students answer such questions on their own grounds.

[5] “And then a rocket sprang and bang shot blind blank and O! then the Roman candle burst and it was like a sigh of Oh! and everyone cried O! O! in raptures and it gushed out of it a stream of rain gold hair threads and they shed and ah! they were all greeny dewy stars falling with golden, O so lovely, O, soft, sweet, soft!” (1986: 300).

[6] I once heard of an Irish fellow who first bought and read Ulysses because he spotted it in a store that sold pornographic books. A good teacher could explain that Ulysses criticizes precisely the fiction it was placed with on the shelf.

.![]()

![]()

![]()

.

Works Cited:

Abbot, Andrew. 2002. “The Aims of Education Address.” University of Chicago Record, 21 November, 4–8.

Augustine. 1991. Confessions, trans. Henry Chadwick. New York: Oxford University Press.

Calvino, Italo. 1993. Six Memos for the Next Millennium. New York: Vintage International.

Delbanco, Andrew. 1999. “The Decline and Fall of Literature.” New York Review of Books 46: 32–38.

Dickinson, Emily. 1963. The Poems of Emily Dickinson, ed. Thomas Johnson. Vol. 2. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University.

Duncan, David James. 2002. The River Why. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books.

Eliot, George. 2000. Middlemarch. New York: Modern Library.

Joyce, James. 1986. Ulysses. New York: Vintage Books.

Percy, Walker. 1991a. “Accepting the National Book Award for The Moviegoer.” In Signposts in a Strange Land, ed. Patrick Samway, 245–46. New York: Picador.

———. 1991b. “Why Are You Catholic?” In Signposts in a Strange Land, ed. Patrick Samway, 304–15. New York: Picador.

Richter, David. 1998. The Critical Tradition: Classic Texts and Contemporary Trends. 2nd ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Webster, John. 1927. The Complete Works of John Webster, ed. F. L. Lucas. Vol. 2. London: Chatto and Windus.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Images:

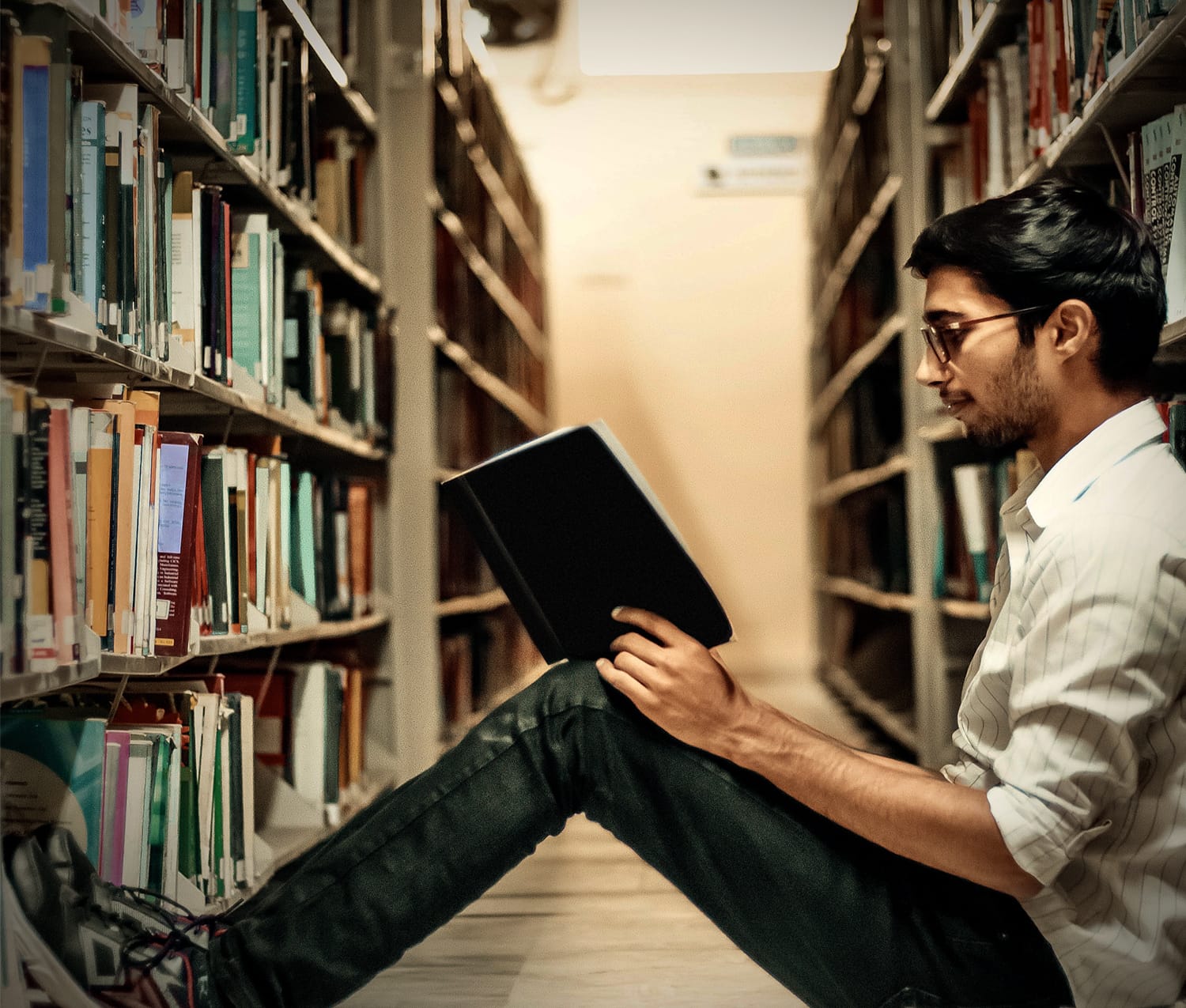

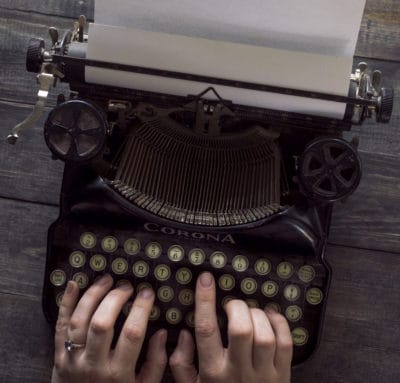

1) Title image: Photo by Dollar Gill on Unsplash (lightly retouched)

2) Library Stacks: Photo by Ali Bergen on Unsplash

3) Fanned Book: Photo by Mishaal Zahed on Unsplash

4) Students: Photo by Alexis Brown on Unsplash

5)Middlemarch cover: George Eliot, Public domain via Project Gutenberg- https://www.gutenberg.org/files/145/145-h/145-h.htm

6) Stacked books: Photo by Alexander Grey on Unsplash

7) The Duchess of Malfi – Title page: John Webster, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

8) Ulysses 1st edition cover: James Joyce, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

9) In conclusion/Scattered Books: Photo by Gülfer ERGİN on Unsplash

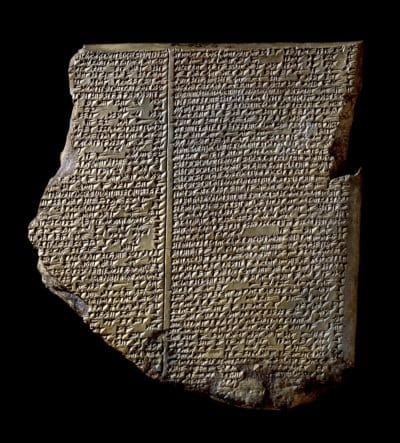

hy are books written, if not for a reader’s enjoyment? People have been telling stories since the dawn of time. As Ursula K. Le Guin points out, “There have been great societies that did not use the wheel, but there have been no societies that did not tell stories.”

hy are books written, if not for a reader’s enjoyment? People have been telling stories since the dawn of time. As Ursula K. Le Guin points out, “There have been great societies that did not use the wheel, but there have been no societies that did not tell stories.”

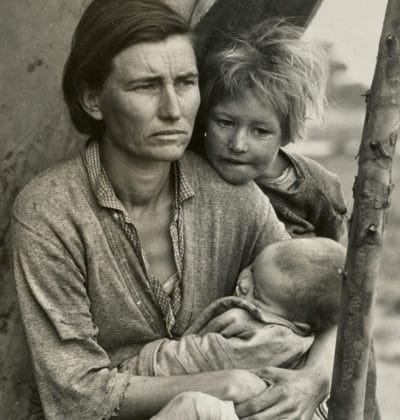

he first thing we notice about a birthday cake is the icing. And who doesn’t love a good butter cream or chocolate ganache. But there’s more to these delicious delicacies than just frosting. Without the rich, baked layers upon which it rests, a cake’s icing would be little more than a puddle of sugary goo. Admittedly delicious, but definitely lacking substance.

he first thing we notice about a birthday cake is the icing. And who doesn’t love a good butter cream or chocolate ganache. But there’s more to these delicious delicacies than just frosting. Without the rich, baked layers upon which it rests, a cake’s icing would be little more than a puddle of sugary goo. Admittedly delicious, but definitely lacking substance.

eading literature is more than being swept along by the charm of the characters, anticipation for the next shocking twist, or the thrill of the events on display. But it can be tricky.

eading literature is more than being swept along by the charm of the characters, anticipation for the next shocking twist, or the thrill of the events on display. But it can be tricky.