All American Boys: A Journey From Passive To Active Voice.

A

A

ll too often, people thumb their noses at English majors, trivializing the subject as the pointless study of irrelevant stories. But, All American Boys by Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely depicts what a powerful effect the written word can have on a reader. How the stories that books tell can give us insight into the events unfolding around us.

And as it happens, the grammar lesson on passive versus active voice detailed in All American Boys is the key to this reading of Reynolds and Kiely’s work.

What’s The Conversation?

Broadly speaking, All American Boys is about two high school students, Rashad Butler and Quinn Collins, and their encounters with racism and police brutality within their community. Specifically, an instance of excessive force captured on video, and its impact on the Black victim, a casualty of racial profiling who was in fact innocent of the petty theft he was accused of. As well as the effect this turn of events has on the white classmate who happens to be a witness to the beating that landed its recipient in the hospital… not to mention being a close family friend of the offending officer.

The book’s epigraph (by Hillel the Elder) points toward the questions Rashad and Quinn come to ask themselves as a result of their experiences with this incident – which also sets up how All American Boys is formatted:

If I am not for myself, who will be for me?

But if I am only for myself, what am I? [1]

.

The text is written in alternating voices emulating a dialogue, one we would benefit enormously from having as a nation. As Brandon Kiely noted in a recent interview, referencing Martin Luther King Jr.’s “The Other America” speech, these voices reflect the two very different Americas living side-by-side in this nation.[2]

Rashad’s voice, written by Jason Reynolds, addresses the first line of Hillel’s quote – the way racism operates in society, including how violence against Black people has been normalized. And the effect that has on the identity of those subjected to it.

Quinn’s voice, written by Brendan Kiely, speaks to the second line of Hillel’s quote – in the context of privileged (and one might say oblivious) nature of white existence when it comes to racism and police brutality in The United States.

Passive Versus Active Voice.

Which brings us to how Mrs. Tracey’s lesson on passive versus active voice functions to inform a reading of All American Boys.

Rashad is falsely accused of shoplifting from a local convenience store and is violently beaten by a police officer, despite his lack of resistance. Needless to say, Rashad’s situation becomes the talk of his school. And, students are divided between “the officer was just doing his job” faction and an “it was racial-profiling-inspired police brutality” contingent.

While sitting in Mrs. Tracey classroom as she addresses Rashad’s absence and how the circumstances surrounding it have affected the student body, Quinn notices her notes on the whiteboard about passive versus active voice.

And, he comes to realize that this lesson on passive versus active voice is relevant to the incident that has the entire school community in an uproar.

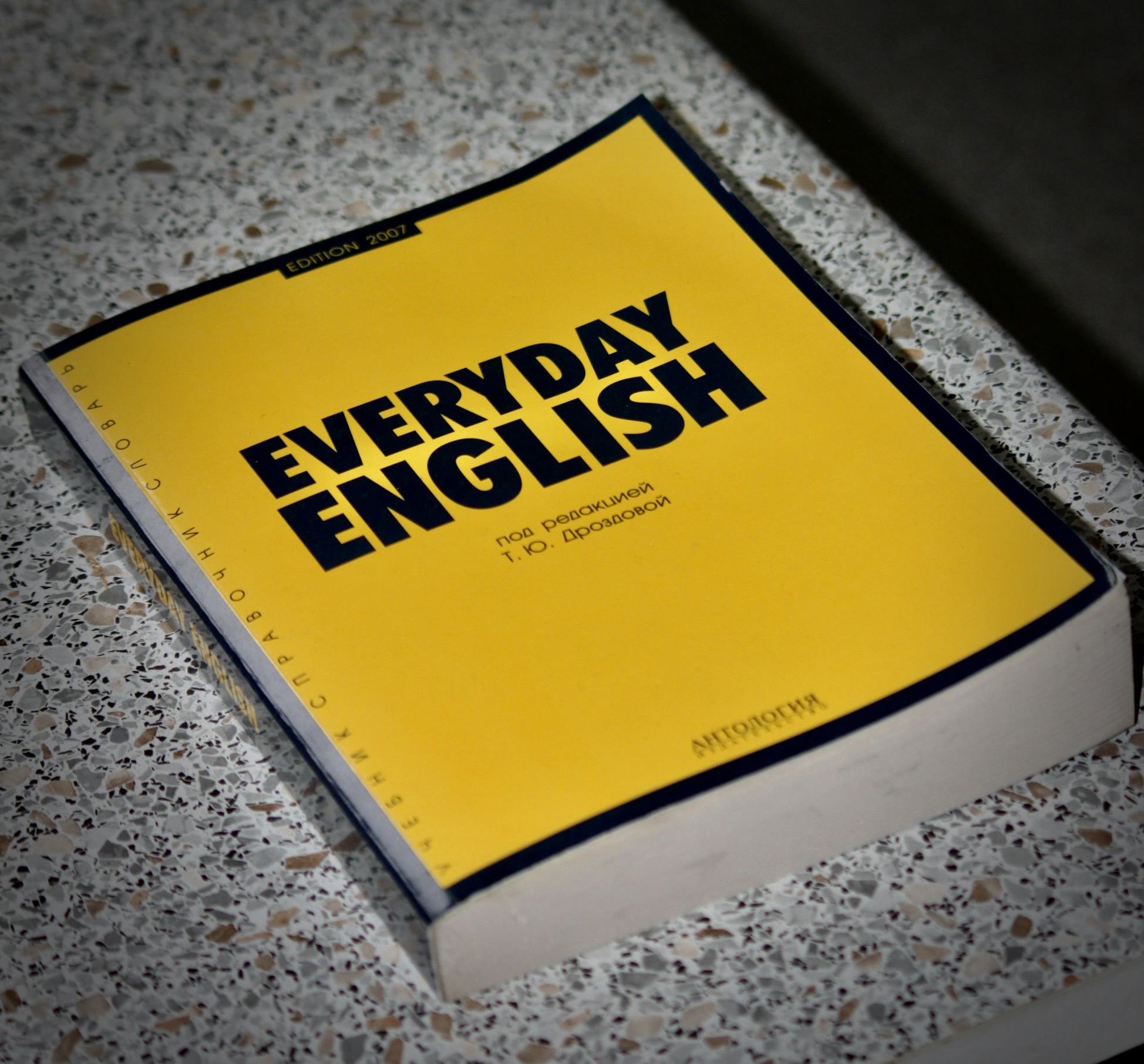

For those who may benefit from a refresher… passive voice is when the subject of the sentence is the recipient of the action. For example: The lamp was knocked over by Tommy. Active voice, on the other hand, is when the subject of the sentence is the one performing the action. As in: Tommy knocked over the lamp.[3]

“’Mistakes were made,’ Mrs. Tracey had scrawled on the white board. And beneath it she’d written, Who? Who made mistakes?”

Mistakes were made.

Rashad was beaten.

Paul beat Rashad.[4]

.

Quinn comes to understand that framing this instance of police brutality in a passive voice (as accounts of the incident had been) allows society to avoid accountability. It’s also important to note that describing the episode in passive voice discounts Rashad’s humanity and denies him agency.

Passive Beginnings.

Up until now, Rashad and Quinn have both lived pretty passive lives, meaning they have simply received actions/ assimilated life-shaping information from their parents and others in their social circles pretty much without question. The incident at Jerry’s market, however, triggers a metamorphosis in both boys from passive to active voice, as it were – to take action rather than simply fall in line their circle of friends and family.

The novel opens with Rashad’s story about how he joined the ROTC “to get [his] dad off [his] back. To make him happy.”[5] The more we learn about Rashad, the more apparent it becomes that he’s the good kid his father expects him to be.

And the more we read about how carefully Rashad is being raised, the more evident it becomes that his father’s concerns are in response to the negative way young black men are frequently characterized in the U.S. This perspective is demonstrated by the fact that Rashad’s father has definitely had “the talk” with his teenage son… that is, how to survive as a Black man when encountering authority.

This message has been drilled into Rashad’s head with a military-style cadence chanted frequently in call-and-response style with his father:

Never fight back. Never talk back. Keep your hands up. Keep your mouth shut. Just do what they ask you to do, and you’ll be fine. [6]

.

In other words, remain passive. Which ultimately fails to protect Rashad from racial profiling and police violence.

Quinn is a star athlete on the basketball team, and one of the school’s leading prospects for the college scouts scheduled to visit in the next few days. He’s a popular student, and loyal son to his father – a soldier who was killed in Afghanistan. He’s also a dutiful son to his mother, whose lessons occupy his mind as he begins nearly every day:

Ma’s voice in my head, telling me what I needed to do, what I needed to think about, how I needed to act. [7]

.

The favorite teenage hang out in town is a pizza joint called Mother’s. A picture of Quinn’s father hangs on the wall amid photos of those who work in the family-run pizza shop. He’s dressed in his Class A blues alongside “two guys in greasy T-shirts with their arms up around [his] dad’s shoulders.”[8] Quinn’s father is nothing short of revered there. And, Quinn notes that he “[has] it good at Mother’s”:

…the guys at Mother’s always gave Saint Springfield’s son a major discount, and yeah, well, I was the kind of guy who just kept taking those free Cokes no questions asked, like I actually deserved them or something.[9]

.

Clearly, both young men are still passively functioning within the patterns and rhythms created by their families. One of them in an effort to navigate a world where “Black men are at disproportionate risk of death from lethal force by law enforcement compared to white men.”[10] And the other, living a life of relative privilege, blissfully unaware of such statistics.

If I Am Not For Myself,

Who Will Be For Me?

We also learn that Rashad is an artist. And, a significant detail about Rashad’s art is that his subjects are faceless. Which is precisely how Rashad feels as he lay in the hospital bed watching the news coverage of the incident that put him there – just another victim:

I had seen this happen so many times. Not personally, but on TV. In the news. People getting beaten, and sometimes killed, by the cops, and then there’s all this fuss about it, only to build up to a big heartbreak when nothing happens. The cops get off. And everybody cries and waits for the next dead kid, to do it all over again. That’s the way the story goes.[11]

.

It feels like the news coverage of the incident at Jerry’s, complete with video captured by an onlooker, is running on a loop. Not only does Rashad repeatedly see himself “being crushed under the weight of the cop,” he hears the recurring insinuation that he was yet another perpetrator in a “string of robberies” at Jerry’s.[12]

Feeling as forlorn as he does, Rashad is inclined to remain passive, and blow off the rally against police brutality that was sparked by the incident he was involved in. That is, until he meets Mrs. Fitzgerald, an elderly lady who works in the hospital gift shop.

Mrs. Fitzgerald tells Rashad a story about her brother, who participated in the Civil Rights protests and “took the bus trip down to Selma.”[13] He begged her to go. But, she didn’t. Because she was scared.

Sounding very much like the sentiments Rashad has expressed about police brutality, Mrs. Fitzgerald told her brother “it didn’t matter.” [14]

But as she watched the clips on the news, she began to regret not joining her brother in the Civil Rights protest in Selma and the March on Washington. Because she came to realize how courageous he was, and that he was not protesting only for himself, but for “all of us.”[15]

Mrs. Fitzgerald gives Rashad a piece of advice that sets his “active voice” in motion:

Now, I’m not telling you what to do. But I’m telling you that I’ve been watching the news, and I see what’s going on. There’s something that ain’t healed, and it’s not just those ribs of yours. And it’s perfectly okay for you to be afraid, but whether you protest or not, you’ll still be scared. Might as well let your voice be heard, son, because let me tell you something, before you know it you’ll be seventyfour and working in a gift shop, and no one will be listening anymore.[16]

.

Rashad thinks about what Mrs. Fitzgerald had to say and how he would feel if he didn’t go to the protest, if he didn’t, as she said, “speak up.”[17] He turns on the TV, and sits and watches the news. But this time, he really watches it, forcing himself to see himself, to relive the pain and confusion. And, how his life changed “in the time it took to drop a bag of chips on a sticky floor.”[18] Then, he picks up his sketch pad:

And started drawing like crazy, but it was hard—stupid damn tears kept wetting the page, they wouldn’t stop, but neither would I. So I kept going, letting the wet spread the lead in weird ways as I shaded and darkened the image. The figure of a man pushing his fist through the other man’s chest. The other figure standing behind, cheering. A few minutes more, and normally it would’ve been complete. A solid piece, maybe even the best I had ever made. But it wasn’t quite there yet. It was close, but still unfinished. I took my pencil, and for the first time broke away from Aaron Douglas’s signature style. Because I couldn’t stop—and I began to draw features on the face of the man having his chest punched through. Starting with the mouth.[19]

.

Rashad has found his voice. And, bearing that in mind, he does march in the protest. As a symbolic gesture, he removes his bandages prior to the protest, because he wants people to see what happened. He wants them to know that regardless of whether Officer Galluzzo gets off scot-free, and this day ends up like other protests sparked by police brutality visited upon young Black men, that he would never be the same person.

In the midst of the protest, Rashad notes:

I knew it wasn’t just about me. I did. But it felt good to feel like I had support. That people could see me.[20]

.

Rashad has evolved from being the recipient of the action, to someone taking action. He is no longer being forced by outside pressures, appearing as a stereotype to be co-opted by those in power. Rashad has developed into a self-affirming individual taking a publicly antiracist stance. Consequently, people genuinely see him and his earnest nature. And, as Hillel predicted, they are for him.

But If I Am Only For Myself,

What Am I?

As noted above, Quinn is a witness to the police brutality that put Rashad in the hospital. The following Monday “everyone – everyone— was talking about” the video of the incident.[21] Everyone, that is, except Quinn because he doesn’t want to put himself back there, watching it happen all over again.

But, more significantly, it occurs to Quinn that he might be in the video, which makes him start “freaking out.”[22] And, that’s more than a little self-absorbed given how things turned out for Rashad.

During a conversation with his friend Jill, Quinn is relieved to discover that he isn’t in the video after all. But, Jill also brings it to his attention in no uncertain terms that “This is not about you, dumb*ss.”[23] And, the proverbial light bulb begins to flicker for Quinn about the larger implications of what transpired at Jerry’s the previous Friday.

A couple days later, Mrs. Tracey enters her classroom with a copy of the novel Invisible Man in her hand. She had assigned the first chapter a week earlier, which Ralph Ellison originally published as a short story titled Battle Royal.

Quinn had never read anything like it, and doing so made him “twisted up in discomfort.”[24] He hated the violence, and how the white men in the story watched Black boys getting beaten, and beat each other, for sport. But, Quinn tells himself, in passive thinking born of obliviousness:

White people were crazy back then, eighty years ago, when the story took place. Not now. [25]

.

Mrs. Tracey tells the class that the school’s administrators have decided it would be best to just move on to the next unit rather than assign a paper for this story as they usually did. It seems Battle Royal hits a little too close to home. The obvious parallels between Ellison’s story and the incident at Jerry’s would likely lead to discussions about Rashad and why he has been absent from school. So, no papers would be written on this unit.

And that’s when Quinn begins to understand what Ralph Ellison meant by the title Invisible Man… when it really starts to sink in:

…a weight of dread dropped through me. Were we going to talk about the story again? After Rashad? Because after what had happened to Rashad, it felt like no time had passed at all. It could have been eighty years ago. Or only eight. Now it wasn’t only the city aldermen. Now there were the videos, and we were all watching this sh*t happen again and again on our TVs and phones – shaking our heads but doing nothing about it.[26]

.

Quinn sees what was in Ellison’s text about invisibility. Why shouldn’t their classes talk about what happened to Rashad? “Was what happened to him invisible? Was he invisible?”[27]

So, Quinn instigates a spontaneous read-aloud of Ellison’s work in class. And, it fell upon him to read the old grandfather’s deathbed advice,a passage reminding everyone in class “what had to be learned by the ‘young’uns:”[28]

Grandfather had been a quiet old man who never made any trouble, yet on his deathbed he had called himself a traitor and a spy, and he had spoken of his meekness as a dangerous activity.[29]

.

Quinn’s proverbial light bulb is becoming increasingly brighter. It becomes clear to him that being passive does nothing but maintain the status quo, keeping marginalized communities invisible:

It was like Jill had said. Nobody wants to think he’s being a racist, but maybe it was a bigger problem, like everyone was just ignoring it, like it was invisible. Maybe it was all about racism? I hated that sh*t, and I hated thinking it had so much power over all our lives—even the people I knew best. Even me.[30]

.

New understandings like Quinn’s is why reading books about people whose lives are different than our own is so important. Doing so gives us insight into societal issues we haven’t experienced, or may not even be aware of because they aren’t happening to us – even when those things are happening to people we may work alongside or go to school with.

Quinn’s description of this dynamic as it pertains to his relationship with Rashad – or lack thereof – is spot-on:

We lived in the same godd*mn city, went to the same godd*mn school, and our lives were so very godd*mn different.

Why? You’d think we’d have so much in common, for God’s sake. Maybe we even did. And yet, why was there so much sh*t in between us, so much sh*t I could barely even see the guy?[31]

.

Sometimes, violence like Ellison talks about (which is purportedly the reason for his work being banned) is a regular part of what some folks contend with on a daily basis. Not to mention the fear of being on the receiving end of racial profiling and police brutality (which All American Boys has been banned for addressing). But, we would never know such injustices exist, or more importantly feel called to address them, if all we know about the world has been limited to the bubble of a single perspective.

Ellison’s work, and its relevance to the police brutality Rashad has experienced, pops the proverbial bubble Quinn has been living in. Battle Royal is Quinn’s wake-up call:

Well, where was I when Rashad was lying in the street? Where was I the year all these black American boys were lying in the streets? Thinking about scouts? Keeping my head down like Coach said? That was walking away. It was running away, for God’s sake. I. Ran. Away. F*ck that. I didn’t want to run away anymore. I didn’t want to pretend it wasn’t happening. I wanted to turn around and run right into the face of it… [32]

.

Quinn has come to realize that part of the privilege his whiteness affords is the notion that injustices he witnesses can be ignored. That it’s easier to diagnose racism as a social problem than confront it on an individual level.

So, he finds a fat, black permanent market, digs up one of his white t-shirts, and writes I’M MARCHING on the front of it – referring of course to the protest against police brutality scheduled for that weekend. Then, he writes ARE YOU? On the back of the shirt. And, he wore that shirt to school the next day.

This new perspective allows Quinn to break free from the blind loyalty his tight knit circle (which includes the offending police officer’s family) expect from him. The type of loyalty they associate with Quinn’s father and his military service. Even though this hard choice cost him a busted lip at the hands of someone he previously counted as his best friend:

Your dad was loyal to the end,’ they’d all tell me. ‘Loyal to his country, loyal to his family,’ they meant.[33]

.

Quinn wants to be his father’s son, as the saying goes. But, he also realizes that the thing his dad was most loyal to was his belief that a better world was possible. And, he was someone who stood up for it, not just for those in his immediate circle.

Quinn has clearly contemplated Hillel’s question, “But if I am only for myself, what am I?” And as a result, he has evolved from seeing the world in a passive and narrow manner, to engaging the world and actively addressing injustices that exist outside his limited circle.

A Die-In. Sort Of Like

The Sit-ins Back in The Day.

After Rashad returns home from the hospital, he goes straight to his room and begins to “scour the Internet” to catch up on his life. The hashtag #RashadIsAbsentAgainToday brought hundreds if not a thousand posts from all around the country.

There were pictures of people carrying posters with the hashtag written on them. Others simply read ABSENT AGAIN. And then, there was the picture of some guy with a T-shirt that said I’M MARCHING on the front, and ARE YOU? written on the back.

The protest is to start at Jerry’s at 5:30 on Friday afternoon and work its way down to the police station. It would culminate in a Die-In – which is sort of like the sit-ins during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. Rashad’s brother Spoony pulls a stack of papers out of his bag, and says:

Then we make the most powerful statement we can make.” Spoony dug in his bag and pulled out a stack of papers. “We read every name on this list. Out loud… [34]

.

The list, of course, contains the names of unarmed Black people who have been killed by the police, enough names to fill several sheets of paper.

And, the protest turns out to be much more than just a handful of high school students. The street was a river of people, with Rashad at the front of the march. “Speaking truth to power. Standing up for injustice.”[35] And it goes off without a hitch.

During the protest Quinn makes a video of himself for his younger brother, stating:

If [Dad] died for freedom and justice – well, what the hell did he die for if it doesn’t count for all of us? [36]

.

Quinn’s video narration could be described as his version of “what had to be learned by the young’uns.”

In Conclusion.

Despite the fact that Rashad and Quinn’s stories are so intertwined, the two never actually meet each other. And, that’s important to note, because as Jason Reynolds pointed out it in a recent interview, a “kumbaya moment” at the close of the novel, “where everything is right with the world,” wouldn’t be reality.”[37] But most of all, “you don’t need to actually know a person to care about their well-being.”[38]

The final chapter is written as a poem. Like the overall format of the novel, it consists of alternating stanzas between each narrator:

Oh my God! He was right over there!

Closer than I’d been to him when

Paul laid into him. Much closer.

And Rashad was looking at me, too.

I locked eyes with a kid I didn’t know, but

felt like I did. A white guy, who I could tell

was thinking about those names too.

All I wanted to do was see the guy I hadn’t

seen one week earlier. The guy beneath

all the bullshit too many of us see first—

especially white guys like me who just haven’t

worked hard enough to look behind it all.

Those people. I hadn’t known any of them,

and he probably hadn’t either. But I was

connected to those names now, because

of what happened to me. We all were. I

was sad. I was angry. But I was also proud.

Proud that I was there. Proud that I could

represent Darnell Shackleford. Proud

that I could represent Mrs. Fitzgerald—

her brother who was beaten in Selma.

I wanted him to know that I saw him,

a guy who, even with a tear-streaked

face, seemed to have two tiny smiles

framing his eyes like parentheses, a guy

on the ground pantomiming his death

to remind the world he was alive.

For all the people who came before

us, fighting this fight, I was here,

screaming at the top of my lungs.

Rashad Butler.

Present.[39]

The poem speaks to the third enduring question posed by Hillel some two thousand years ago:

And, if not now, when? [40]

.

Though Hillel’s third enduring question isn’t included in the novel’s epigraph, its sentiment is implied throughout All American Boys. The incident at Jerry’s shakes both Rashad and Quinn out of a passive tendency to stick with their respective herds, if you will, sparking them to actively address the racial injustices that continue to occur in the United States.

Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man prompted the proverbial light bulb to flicker for Quinn. Reading All American Boys is also an eye-opening experience. One that has the capacity to pop the bubble many of us have been living in. And, be a catalyst for transforming readers from being passive members of society to taking action toward making the world a better place. This is the power of literature, whether it’s a classic novel like Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, or a new favorite like All American Boys by Jason Reynolds and Brandon Kiely.

That’s my take on All American Boys, what’s yours?

Share This Post, Choose a Platform!

Endnotes:

[1] Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. All American Boys. New York: Antheum Books for Young Readers, 2015, epigraph.

[2] “All American Boys.” Velshi Banned Book Club: Police brutality, white privilege, and “All American Boys.” https://www.ms.now/ali-velshi/watch/velshibannedbookclub-police-brutality-white-privilege-and-all-american-boys-159483973820

[3] “Active Versus Passive Voice.” Purdue Online Writing Lab. https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/academic_writing/active_and_passive_voice/active_versus_passive_voice.html

“Active vs. Passive Voice: What’s the difference?” Merriam-Webster Dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/grammar/active-vs-passive-voice-difference

[4] Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. All American Boys. New York: Antheum Books for Young Readers, 2015, Pg 213.

[5] Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. All American Boys. New York: Antheum Books for Young Readers, 2015, Pg 9.

[6] Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. All American Boys. New York: Antheum Books for Young Readers, 2015, Pg 50.

[7] Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. All American Boys. New York: Antheum Books for Young Readers, 2015, Pg 63.

[8] Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. All American Boys. New York: Antheum Books for Young Readers, 2015, Pg 77.

[9] Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. All American Boys. New York: Antheum Books for Young Readers, 2015, Pg 78.

[10] Ramos, Jill Terreri. Politifact. https://www.politifact.com/factchecks/2021/apr/29/kevin-parker/police-violence-leading-cause-death-young-black-me/

[11] Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. All American Boys. New York: Antheum Books for Young Readers, 2015, Pg 59.

[12] Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. All American Boys. New York: Antheum Books for Young Readers, 2015, Pg 94.

[13] Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. All American Boys. New York: Antheum Books for Young Readers, 2015, Pg 245.

[14] Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. All American Boys. New York: Antheum Books for Young Readers, 2015, Pg 245.

[15] Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. All American Boys. New York: Antheum Books for Young Readers, 2015, Pg 245.

[16] Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. All American Boys. New York: Antheum Books for Young Readers, 2015, Pg 245.

[17] Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. All American Boys. New York: Antheum Books for Young Readers, 2015, Pg 246.

[18] Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. All American Boys. New York: Antheum Books for Young Readers, 2015, Pg 246.

[19] Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. All American Boys. New York: Antheum Books for Young Readers, 2015, Pg 246.

[20] Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. All American Boys. New York: Antheum Books for Young Readers, 2015, Pg 306.

[21] Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. All American Boys. New York: Antheum Books for Young Readers, 2015, Pg 123.

[22] Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. All American Boys. New York: Antheum Books for Young Readers, 2015, Pg 128.

[23] Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. All American Boys. New York: Antheum Books for Young Readers, 2015, Pg 130.

[24] Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. All American Boys. New York: Antheum Books for Young Readers, 2015, Pg 212.

[25] Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. All American Boys. New York: Antheum Books for Young Readers, 2015, Pg 212.

[26] Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. All American Boys. New York: Antheum Books for Young Readers, 2015, Pg 213.

[27] Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. All American Boys. New York: Antheum Books for Young Readers, 2015, Pg 215.

[28] Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. All American Boys. New York: Antheum Books for Young Readers, 2015, Pg 217.

[29] Ellison, Ralph. Invisible Man. Vintage Books, 1995, Pg 16.

[30] Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. All American Boys. New York: Antheum Books for Young Readers, 2015, Pg 262.

[31] Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. All American Boys. New York: Antheum Books for Young Readers, 2015, Pg 261.

[32] Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. All American Boys. New York: Antheum Books for Young Readers, 2015, Pg 251.

[33] Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. All American Boys. New York: Antheum Books for Young Readers, 2015, Pg 267.

[34] Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. All American Boys. New York: Antheum Books for Young Readers, 2015, Pg 282.

[35] Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. All American Boys. New York: Antheum Books for Young Readers, 2015, Pg 294.

[36] Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. All American Boys. New York: Antheum Books for Young Readers, 2015, Pg 294.

[37] “All American Boys.” Velshi Banned Book Club: Police brutality, white privilege, and “All American Boys.” https://www.ms.now/ali-velshi/watch/velshibannedbookclub-police-brutality-white-privilege-and-all-american-boys-159483973820

[38] “All American Boys.” Velshi Banned Book Club: Police brutality, white privilege, and “All American Boys.” https://www.ms.now/ali-velshi/watch/velshibannedbookclub-police-brutality-white-privilege-and-all-american-boys-159483973820

[39] Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. All American Boys. New York: Antheum Books for Young Readers, 2015, Pg 309-310.

[40] Rev. Shawn Newton. “The Three Vital Questions.” First Unitarian Congregation of Toronto. December 11, 2022. https://www.firstunitariantoronto.org/wp-content/sermons/2022/2022-12-11%20Shawn%20Newton%20-%20The%20Three%20Vital%20Questions.pdf

Images:

What’s the Conversation?: Photo by autumn_ schroe on Unsplash

Passive versus Active voice: Photo by Ivan Shilov on Unsplash

Passive Beginnings: Photo by Stanley Emrys on Unsplash

If I am not for myself, who will be for me?: Photo by Reneé Thompson on Unsplash

But if I am only for myself, what am I?: Photo by Alonso Reyes on Unsplash

A Die-in: Photo by Ehimetalor Akhere Unuabona on Unsplash

In Conclusion: Photo by Koshu Kunii on Unsplash

Share This Post, Choose a Platform!

Stay in the know about what’s in our treasure trove of literary goodness. And, get your free Discover Everything a Book Has to Offer packet.