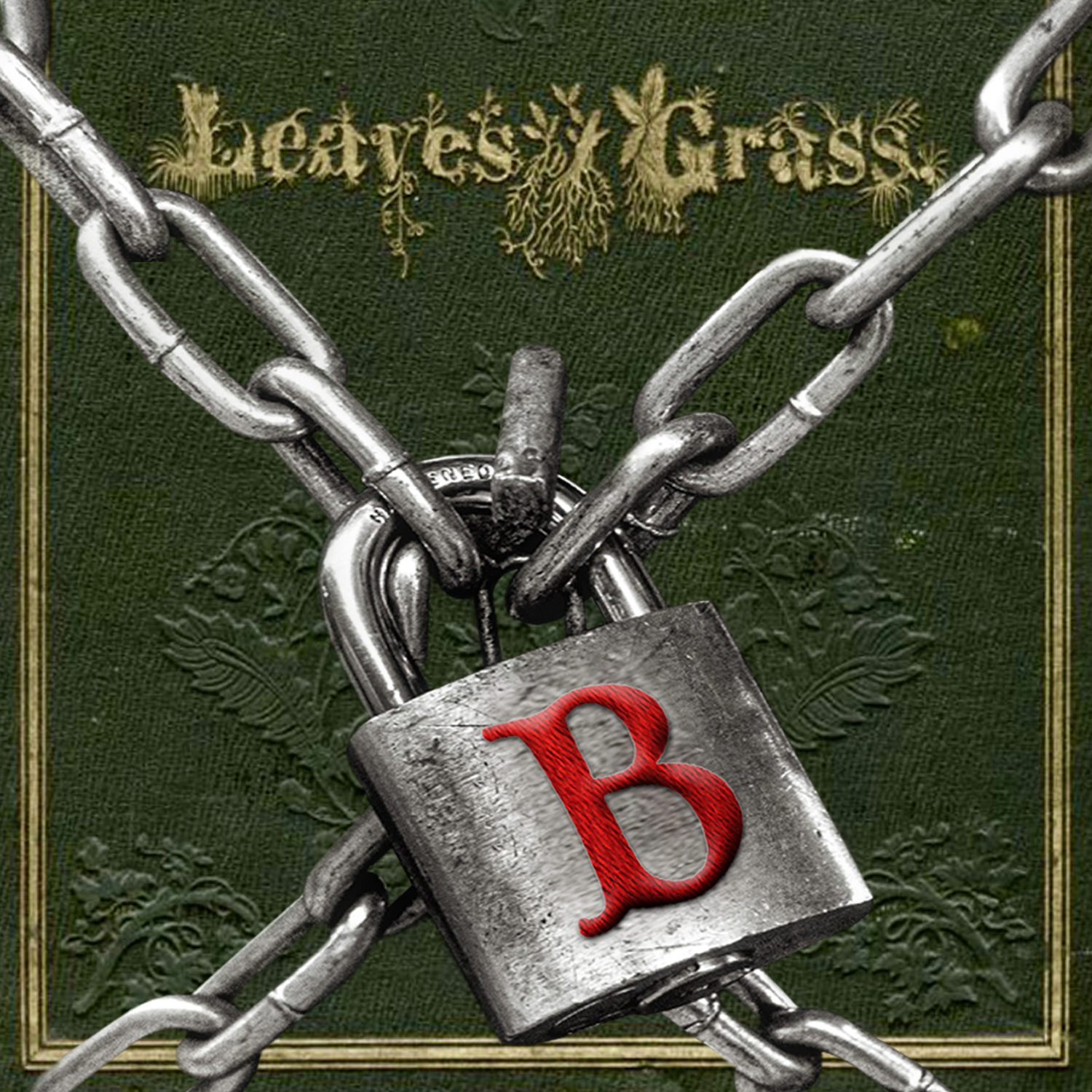

Leaves of Grass: A celebration of American democracy

W

W

alt Whitman (or Uncle Walt as Robin Williams referred to him in the film Dead Poet’s Society) has been described as “the world’s poet of democracy.”[1] And, Leaves of Grass is his visionary collection of poetry celebrating his belief in democracy and the individual’s place in it.

Leaves of Grass was published little more than 60 years after the United States constitution was ratified. And, Whitman considered this recently established democratic governance to be an inevitable evolutionary force in human history.

That said, he was in no way under the illusion that a functioning democratic society would either come easily or emerge quickly in the still-young nation of his day.

He also believed that democracy would fail if it was strictly legislative and legalistic. And, contended that a democratic literature was the most essential factor in urging this evolution along. Because:

That which really balances and conserves the social and political world is not so much legislation, police, treaties, and dread of punishment, as the latent eternal intuitional sense, in humanity, of fairness, manliness, decorum, &c. Indeed, the perennial regulation, control and oversight, by self-suppliance, is sine qua non to Democracy; and a highest, widest aim of Democratic literature may well be to bring forth, cultivate, brace and strengthen this sense in individuals and society.[2]

.

As long as the country’s imagination remained fueled by literature modeled on works produced under the “opposite influences” of aristocracy and hierarchical, authoritarian structures, Whitman maintained, democracy would never flourish.[3]

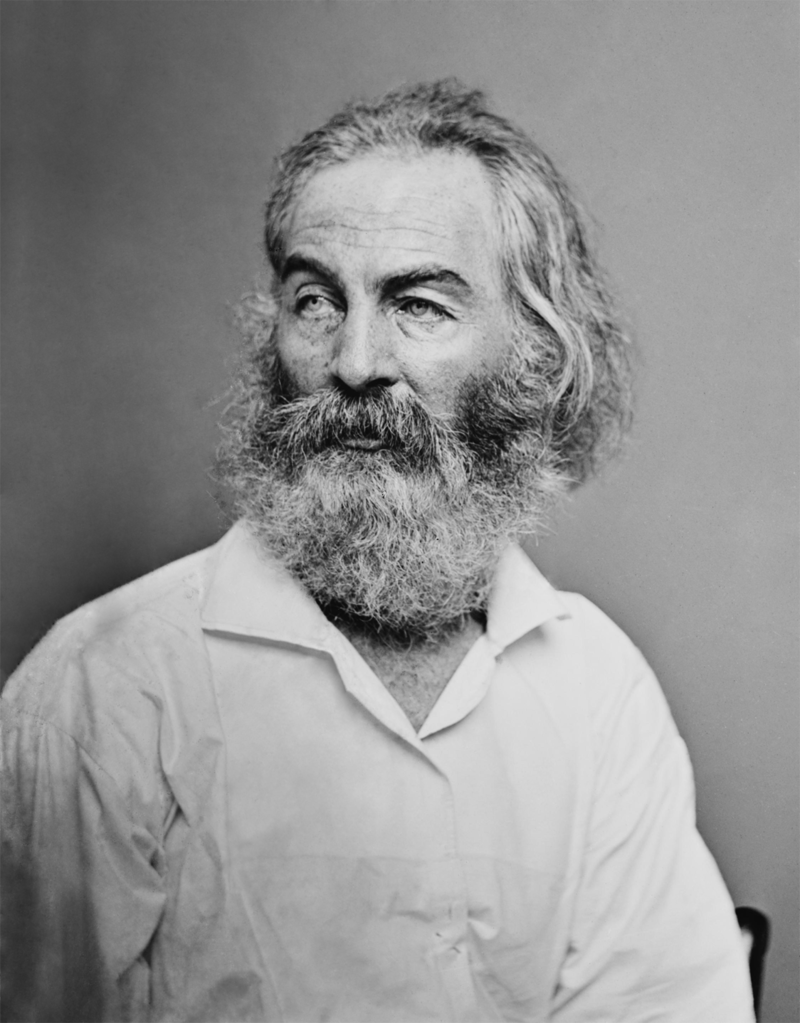

A distinctly American form and style

When Whitman began writing, American poetry sounded pretty much like its British counterpart. Popular poets of the day, like John Greenleaf Whittier and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, wrote in a manner reminiscent of the Victorian style prevalent in England. Their style revolved around the special, the elect, the few.

So, for reasons pointed out above, Whitman wanted to create an original, distinctly American form and style. One that shifted the focus away from the rich & powerful, and stratified social structures. One that championed the everyday people who make up the heart of democracy. One that quells potential animosity between these everyday people by nurturing understanding and cultivating camaraderie.[4]

Whitman’s primary interest was in the way a democratic self would act rather than the way democratic society would function. And, he knew that defining this revolutionary new self would require a more equalizing connection between reader and author.[5]

The style Whitman set out to create would be as open, and nondiscriminatory as he imagined an ideal democracy to be. It would reflect the broad spectrum of American experience. And, most importantly, it would be a democratic voice that would serve as a model for society.[6]

And, he did exactly that. Rejecting traditional poetic conventions, Walt Whitman is widely considered to be the “Father of free verse.”[7] This new form of poetry is a loose, informal style, with no rhyme, or no meter. As such, it better captures the natural rhythms of speech.

He constructed a poetry that breaks down the barriers of bias and convention, requiring acts of imaginative absorption on the part of the reader. Whitman’s poetry directly addresses the reader and challenges him to action. All of which results in an enlarging of the self.

Rather than proposing a particular persona, however, Whitman’s Leaves of Grass offers a tool for discovering his own innate wisdom in developing a democratic identity.[8]

Whitman’s foundational metaphor

The question for Whitman was always one of the “democratic individual” within an “aggregated, inseparable… democratic nationality.”[9] Which makes Leaves of Grass more than simply the title of a collection of poetry – it’s Whitman’s foundational metaphor for democracy itself.

As Alexis de Tocqueville pointed out in 1835, America has a tendency to think as a country of “I’s,” rather a nation of “us.”[10] But, Whitman expresses unlimited optimism on this issue, one that tormented America’s founders… the fear that individualism would deter the public virtue of aligning our individual self-interest with that of the republic’s.[11]

In Whitman’s metaphor, the American people are like grass. No two leaves/blades are alike. Each has a certain kind of individuality. Step back, however, and you’ll see that the leaves/blades are more alike than they are different. Americans can be ourselves to the utmost while also sharing deep kinship with our neighbors.

Who are our neighbors?[12] All the other leaves/blades of grass around us:

Sprouting alike in broad zones and narrow zones,

Growing among black folks as among white,

Kanuck, Tuckahoe, Congressmen, Cuff, I give them the same, I receive them the same.[13]

.

Together, the individual leaves/blades of grass create a lush, verdant quilt that covers the ground. And, when you stand back far enough, you don’t see individual leaves/blades at all, but an organic unity.[14]

It’s a visual representation of what Whitman expresses in the line, “what I assume you shall assume”— that is, assume that our common interest in our own freedom is what, above all else, unites us as Americans.[15]

The individual leaves/blades haven’t disappeared, however. A closer looks lets us know they’re still there, unique and vibrant, no two alike. Whitman’s leaves of grass metaphor is an exquisite example of e pluribus unum, from many one.[16]

Song of Myself

Song of Myself was given priority as the first poem of the collection Leaves of Grass. And rightly so, because it represents the essence of Whitman’s poetic vision.[17]

Consistent with his grass metaphor for democracy, Whitman’s narrator, the “I” who’s celebrating himself, functions in a dual capacity. He isn’t simply speaking as an individual, but as the voice of an aggregated democratic whole. And, this concept is reiterated throughout the work:

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you. (Section 1)

In all people I see myself, none more and not one a barleycorn less,

and the good or bad I say of myself I say of them. (Section 20)

I am large. I contain multitudes. (Section 51)[18]

.

Whitman’s narrator, the “self” in Song of Myself, is clearly speaking as the voice of a equitable collective.

Whitman’s grass metaphor also signifies equality

As noted above, Whitman considered his poem to be, at least in some measure, and American epic. Unlike the epic poetry of Homer, Virgil, or Dante, however, the “self” in Song of Myself isn’t an archetypal hero.

In the Iliad, Homer catalogues the Greek ships, organized according to the importance of the chieftains and warriors they carried. In Paradise Lost, Milton catalogues the major demons who have been cast into hell.

Song of Myself also includes a catalogue. Significantly, the dual capacity on which Whitman’s grass metaphor functions signifies equality within democratic America as well as unity.

So, in keeping with his grass metaphor, Whitman’s catalogue is comprised of everyday American men and women, all one, and all equal.[19] Here is a mere segment:

The conductor beats time for the band and all the performers follow him,

The child is baptized – the convert is making the first professions,

The regatta is spread on the bay… how the white sails sparkle!

The drover watches his drove, he sings out to them that would stray,

The pedlar sweats with his pack on his back – the purchaser higgles about the odd cent,

The camera and plate are prepared, the lady must sit for her daguerreotype,

The bride unrumples her white dress, the minute hand of the clock moves slowly,

The opium eater reclines with rigid head and just-opened lips,

The prostitute draggles her shawl, her bonnet bobs on her tipsy and pimpled neck,

The crowd laugh at her blackguard oaths, the men jeer and wink to each other,

(Miserable! I do not laugh at your oaths nor jeer you,)

The President holds a cabinet council, he is surrounded by the great secretaries, [20]

.

Whitman closes his vast list of fellow Americans with the declaration:

By God! I will accept nothing which all cannot have their counterpart of on the same terms.[21]

.

Understanding that we’re all equal is significant. And, what Whitman is dramatizing with his famous catalogues of everyday people doing everyday things is quite simple. He’s making them manifest in our imaginations, so we come to understand that these are our brothers and sisters.[22]

But that’s simply at the individual level of the grass metaphor. Whitman also urges us to move away from our tendency for rivalrous individuality, to expand our larger self. For, the actual subject of his American epic is the expansion of consciousness and spirit, mind and heart.

At the level of a united whole which this metaphor also functions on – that is, when we leave hierarchical thinking behind, stop looking up at those who are purportedly superior to us, and down at those who seem less than us – we’re free from false constraints and can live joyously as part of a community of equals.[23]

It’s a conversation

As noted above, the free verse Walt Whitman is credited with inventing better captures the natural rhythms of speech. This observation is especially important given that Song of Myself appears to be a dialogue between Whitman and the reader rather than a literary performance.

Significantly, this conversational dynamic is consistent with Whitman’s grass metaphor, in that it culminates in a comradeship between poet and reader – a merger of equals.[24]

Even more conducive to creating the impression of conversation than the absence of rhyme or meter is Whitman’s practice of posing questions directly to the reader.[25] For example:

“Have you reckoned a thousand acres much ? Have you reckoned the earth much?

Have you practiced so long to learn to read ?

Have you felt so proud to get at the meaning of poems? [26]

.

The passage above appears at the beginning of the work, and Whitman follows it with a declaration:

Stop this day and night with me and you shall possess the origin of all poems,

You shall possess the good of the earth and sun… there are millions of suns left,

You shall no longer take things at second or third hand… nor look through the

eyes of the dead… nor feed on the spectres in books,

You shall not look through my eyes either, nor take things from me,

You shall listen to all sides and filter them from yourself.[27]

.

At this point, speaker and reader are two separate individuals, with the poet as teacher. By the end of the passage, however, the poet makes it clear that the reader will eventually no longer be a student, that they will ultimately become equals.

By the middle of Song of Myself, Whitman indicates to the reader that they now play a larger role than merely processing the words on the page:

Listener up there! what have you to confide to me?

Look in my face while I snuff the sidle of evening,

Talk honestly, no one else hears you, and I stay only a minute longer.[28]

.

Obviously, it isn’t possible for the poet to actually listen to what the reader may have to say. This exchange is meant to set the reader’s emotional and intellectual wheels in motion, as the saying goes. It’s intended to engage the reader in a way beyond that of simply ingesting what Whitman tells them. The reader is no longer taking things at second or third hand… or from the poet for that matter.

In the final segments of the poem Whitman returns to his foundational metaphor:

I bequeath myself to the dirt to grow from the grass I love,

If you want me again look for me under your bootsoles.

You will hardly know who I am or what I mean,

But I shall be good health to you nevertheless,

And filter and fibre your blood. [29]

.

The speaker and reader have now merged, the poet symbolically filtering the reader’s blood, as fibres in their muscles. In true democratic fashion, they function together to nurture the democracy Whitman is celebrating.

In the poem’s concluding stanza, the speaker’s journey is complete:

Failing to fetch me at first keep encouraged,

Missing me one place search another,

I stop some where waiting for you.[30]

.

And now, it’s the reader’s task to carry the democracy that Whitman’s grass symbolizes forward. Fueled by their expanded self, and the democratic spirit conveyed in the poet’s words.

Democracy is ever vulnerable

Whitman was no Pollyanna, however – he understood that democracy is ever vulnerable. He realized that the sight of an egalitarian society – with equal people pursuing their goals and desires – can seem chaotic. So, worship of a king – or some form of autocratic leader – is always tempting.

He admonishes us to remember what the revolutionaries fought for. And, just as importantly, what they fought against. When we forget that, Whitman points out, we’re in danger of lapsing back into the way of kings.[31] The following passage from A Boston Ballad addresses this ever-present concern:

Clear the way there Jonathan!

Way for the President’s marshal! Way for the government cannon!

Way for the federal foot and dragoons… and the phantoms afterward.

I rose this morning early to get betimes in Boston town;

Here’s a good place at the corner… I must stand and see the show.

I love to look on the stars and stripes… I hope the fifes will play Yankee Doodle.

How bright shine the foremost with cutlasses,

Every man holds his revolver… marching stiff through Boston town.[32]

.

Whitman is describing the type of procession seen in countries like Fascist Italy, Communist China, or North Korea. Where the leader is held supreme, and military might is on full display as a threatening reminder to the world… as well as their own people.

He’s alerting us to what’s taking place when we start seeing such displays of concentrated, dominating power. When that happens, we’ve lost sight of the fact that the American revolution was all about fighting a tyrant wielding just this type of power. We might as well:

Dig out King George’s coffin …. unwrap him quick from the graveclothes…

box up his bones for a journey :

Find a swift Yankee clipper …. here is freight for you, blackbellied clipper,

Up with your anchor! shake out your sails!… steer straight toward Boston bay.

Now call the President’s marshal again, and bring out the government cannon,

And fetch home the roarers from Congress and make another procession and guard

it with foot and dragoons.

Here is a centrepiece for them:

Look! All orderly citizens… look from the windows, women!

The committee open the box and set up the regal ribs and glue those that will not stay,

And clap the skull on top of the ribs and clap a crown on top of the skull.

You have got your revenge old buster!… The crown has come to its own and more than its own.[33]

.

How does Whitman advise us to address the fear of chaos, and avoid such a lapse into king-like authoritarian leadership?

By reaffirming the personal bonds of our democracy. By reminding people that we’re involved in what is likely the greatest and most promising social venture of all time… And most importantly, by emphasizing that this grand American experiment requires hard work and vigilance.[34]

In conclusion

Ultimately, Whitman’s message is one of connectedness, kinship defined by receptivity and responsiveness to others. If we can move away from our addiction to rivalrous individuality, and our proclivity toward hierarchy and authoritarian systems, we can embrace his democratic trope of the grass.

Whitman has taken us on a tour of democracy. He’s shown us what we might achieve by following his lead on the subject. When we make this metaphoric grass the national flag, so to speak, we learn to love and appreciate the people around us. We become a community of equals, which makes us less susceptible to tyrannical leaders.

Benjamin Franklin is credited with saying, our form of government is a republic… if we can keep it. As Franklin well knew, maintaining a repudiation of hierarchy and authoritarian systems is not so easy.[35] Whitman’s benefits don’t materialize simply by reading his poem. It takes work – to expand our minds and hearts, to see those around us as our brothers and sisters, to see ourselves as part of a united democratic whole. Democracy takes effort – every day, and from every one of us.

.

That’s my take on Leaves of Grass — what’s yours?

Check out this Discussion Guide to get you started.

Share This Post, Choose a Platform!

Endnotes:

[1] Betsy Erkkila. In “Walt Whitman: Poet of American Democratic Individualism.” By Walter Donway. Online Library, November 30, 2022

https://oll.libertyfund.org/publications/reading-room/2022-11-30-donway-walt-whitman-poet-american-democratic-individualism

[2] Whitman, Walt. Democratic Vistas. Washington, D.C. 1871. Pp 69-70.

[3] Whitman, Walt. Democratic Vistas. Washington, D.C., 1871. Pg 5.

Edmundson, Mark. Song of Ourselves: Walt Whitman and the fight for democracy. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2021. Preface.

[4] Edmundson, Mark. Song of Ourselves: Walt Whitman and the fight for democracy. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2021. Preface.

[5] Folsom, Ed. “Democracy.” The Walt Whitman Archive. Gen. ed. Matt Cohen, Ed Folsom, & Kenneth M. Price.

[6] “Walt Whitman at 200.” Poetry Foundation. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/collections/149913/walt-whitman-at-200

Folsom, Ed. “Democracy.” The Walt Whitman Archive. Gen. ed. Matt Cohen, Ed Folsom, & Kenneth M. Price.

[7] Voigt, Benjamin. “Walt Whitman 101.” PoetryFoundation.org July 1, 2015. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/70243/walt-whitman-101

[8] Hennequet, Claire. “Imagining the Nation. Walt Whitman’s Leaves of grass.”

[9] Whitman, Walt. “Preface, 1872, to As a Strong bird on Pinions Free. (Now, Thou-Mother with thy Equal Brood.)” Complete Prose Works. Philadelphia: David McKay Publishers, 1892. Pg 279.

[10] De Tocqueville, Alexis. Democracy in America. Book 2 (Influence of Democracy on the feelings of Americans.) Chapter II.

[11] Donway, Walter. “Walt Whitman: Poet of American Democratic Individualism.” Online Library, November 30, 2022

https://oll.libertyfund.org/publications/reading-room/2022-11-30-donway-walt-whitman-poet-american-democratic-individualism

[12] Edmundson, Mark. Song of Ourselves: Walt Whitman and the fight for democracy. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2021. Pg 30.

[13] Whitman, Walt. Leaves of Grass. Washington D.C., 1855. Pg 16

[14] Edmundson, Mark. Song of Ourselves: Walt Whitman and the fight for democracy. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2021. Pg 30.

[15] Whitman, Walt. Leaves of Grass. Washington D.C., 1855. Pg 13

[16] Edmundson, Mark. Song of Ourselves: Walt Whitman and the fight for democracy. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2021. Pg 30.

[17] Greenspan, Ezra, ed. Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself”: A Sourcebook and Critical Edition. New York: Routledge, 2005. Pg 3.

[18] Whitman, Walt. Leaves of Grass. Washington D.C., 1855. Pg 13, 26, 53, 55.

[19] Edmundson, Mark. Song of Ourselves: Walt Whitman and the fight for democracy. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2021. Pg 39.

[20] Whitman, Walt. Leaves of Grass. Washington D.C., 1855. Pg 22.

[21] Whitman, Walt. Leaves of Grass. Washington D.C., 1855. Pg 29.

[22] Edmundson, Mark. Song of Ourselves: Walt Whitman and the fight for democracy. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2021. Pg 27.

[23] Edmundson, Mark. Song of Ourselves: Walt Whitman and the fight for democracy. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2021. Pg 21.

[24] Mason, John B. “Questions and Answers in Whitman’s ‘Confab.’” American Literature. Vol. 51, No. 4 (January 1980) Pg 499.

[25] Mason, John B. “Questions and Answers in Whitman’s ‘Confab.’” American Literature. Vol. 51, No. 4 (January 1980) Pg 493.

[26] Whitman, Walt. Leaves of Grass. Washington D.C., 1855. Pg 14.

[27] Whitman, Walt. Leaves of Grass. Washington D.C., 1855. Pg 14.

[28] Whitman, Walt. Leaves of Grass. Washington D.C., 1855. Pg 55.

[29] Whitman, Walt. Leaves of Grass. Washington D.C., 1855. Pg 56.

[30] Whitman, Walt. Leaves of Grass. Washington D.C., 1855. Pg 56.

[31] Edmundson, Mark. Song of Ourselves: Walt Whitman and the fight for democracy. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2021. Pg 56.

[32] Whitman, Walt. Leaves of Grass. Washington D.C., 1855. Pg 89.

[33] Whitman, Walt. Leaves of Grass. Washington D.C., 1855. Pg 90.

[34] Edmundson, Mark. Song of Ourselves: Walt Whitman and the fight for democracy. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2021. Pg 57.

[35] Edmundson, Mark. Song of Ourselves: Walt Whitman and the fight for democracy. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2021. Pg 32-33.

Images:

Leaves of Grass: 1st edition cover. Public Domain

A distinctly American form and style: Brady, Matthew. Walt Whitman. Public Domain

Whitman’s foundational metaphor: Photo by Fauzan Saari on Unsplash

Song of Myself: Hollyer, Samuel. Steel engraving of a daguerreotype by Gabriel Harrison. Morgan Library & Museum. Public Domain

The grass metaphor also signifies equality: Photo by Jonny Gios on Unsplash

It’s a conversation: Photo by Matheus camara da silva on unsplash.com

Democracy is ever-vulnerable: Photo by iStrfry , Marcus on Unsplash

In conclusion: Photo by Zacqueline Baldwin on Unsplash