Power of Books Author Series: Dr. Michael Datcher

![]() E

E

fforts to ban books during the 2022-2023 school year are up 33 percent from the 2021-2022 academic year. And the number of titles targeted for censorship in public libraries has skyrocketed, increasing by 92% in 2023.

And, the books being banned are consistently those of marginalized voices. Books with diverse characters, primarily characters of color and LGBTQ+ characters were overwhelmingly targeted.[1] And continue to be.

Throughout this collection of conversations with authors, we talk about the power of books, and the question of why it’s important for stories containing characters that have diverse backgrounds and life experience to be told.

In considering this vital question, we also touch on the dangers of restricting or erasing these narratives – what damage is being done when books about diversity are banned and reading is restricted?

Needless to say, each of the authors in this series brings s different perspective and life experience to the conversation, adding nuance and depth to the combined answer of why it’s important for stories about diverse lives to be told… as well as the dangers that arise when they’re expunged from our national discourse.

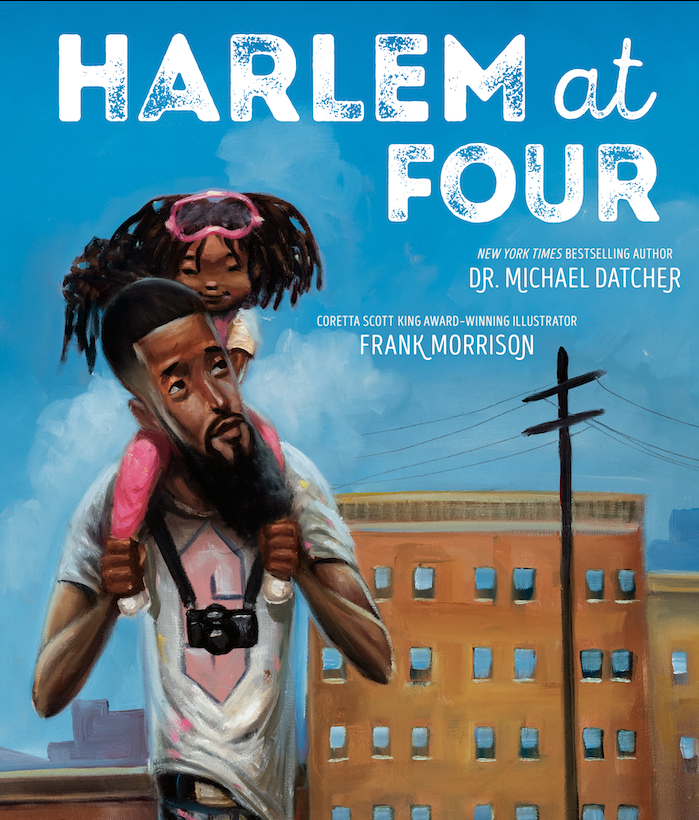

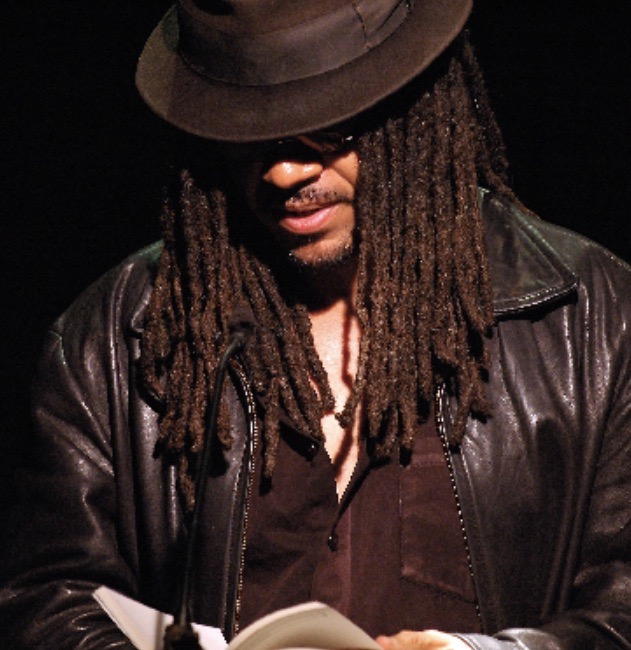

In the inaugural edition of our Power of Books Author Series we talk with Dr. Michael Datcher, author of Harlem at Four.

Dr. Datcher is an engaged scholar and the author of the critically acclaimed New York Times bestseller Raising Fences: A Black Man’s Love Story, (a Today show Book of the Month pick). He is also the author of the Pulitzer Prize-nominated Animating Black and Brown Liberation and co-editor of Tough Love: The Life and Death of Tupac Shakur. His play Silence was commissioned by and premiered at the Getty Museum. And most recently, Harlem at Four, illustrated by Coretta Scott King Award-Winning illustrator Frank Morrison.

Dr. Datcher is an engaged scholar and the author of the critically acclaimed New York Times bestseller Raising Fences: A Black Man’s Love Story, (a Today show Book of the Month pick). He is also the author of the Pulitzer Prize-nominated Animating Black and Brown Liberation and co-editor of Tough Love: The Life and Death of Tupac Shakur. His play Silence was commissioned by and premiered at the Getty Museum. And most recently, Harlem at Four, illustrated by Coretta Scott King Award-Winning illustrator Frank Morrison.

![]() .

.

Teaching is important to me because my life was changed by great teachers. I had been on a very corporate track in my first couple years of college. I come from a very poor family, and I wanted, I guess, just to make money. Then I had these literature professors one semester as an elective who were so amazing that I changed, literally, my entire life. So, I believe in the power of education being transformative. That’s my story, and why I completely believe in education.

.

I couldn’t agree more about the transformative nature of education.

Your children’s book Harlem at Four is gorgeous, but it’s only disguised as a children’s book. It’s for all ages. I learned so much from reading it. I bet your daughter (who the book is named for) is tickled.

![]() .

.

Yeah, she loved it. She was really excited. And it really was a gift for her, so I’m excited that it’s out and that it was published, frankly. It was a chance to surprise her, and honor her and honor our relationship. That’s important to me.

.

Congratulations to both of you. It’s an important book to have out there.

As you know, this website is about banned books and pushing back against book banning. So, clearly that’ll be the topic of conversation today. In keeping with a series of interviews I’m doing on the subject of book banning, why do you think it’s so important for stories about diversity to be told? Especially since those are the types books that are most targeted.

![]() .

.

For Harlem at Four, that book’s important because it reveals a not well-known story about the Harlem Renaissance and so-called Great Black Migration. In the history of America, and probably every country, change happens because individuals make a decision.

This man, Philip A. Payton, bought two buildings around 135th street in Harlem, at what is now Malcolm X Boulevard – then it was called Lenox Ave. His desire for Black folks to have a place to live in that part of the city was important to him, because at the time Blacks could not live in that part of New York.

He was able to buy these two buildings, and he rented them to Black families. His building was the first building which Blacks could actually live in, in Harlem. So, literally this one man’s decision to buy these buildings gave Blacks making their migration from the South, fleeing racial terror, a place to go.

Eventually he bought over twenty buildings. So, he was the foundation of what became the Harlem Renaissance. Because those folks heard by word of mouth that “there’s a guy who bought these buildings in Harlem, and we can live there, etc.” Because when Blacks lived anywhere in New York, their rents were increased. There was a premium, a “Black tax,” basically. And it seems as if Mr. Payton didn’t use that system to put Black people in his buildings.

I wanted to tell that story, so there’s that aspect of Harlem at Four. But also secondly, on a much more personal level, the story of my daughter and I. Harlem and her sister are really “daddy’s girls,” and the discourse around Black men as fathers is that we’re not present. Now, in my life, among my friends, the fathers who I know are very present. They’re great dads.

And, of course, there are non-great dads in every community. But the discourse around Black men is that we’re not present. So I wanted to offer a real-life story of just one Black dad – me – and my youngest daughter.

.

That’s the best way to move things forward is to do what you have done, to put a face on whatever the concept we’re addressing is. There are a lot of different names for it – The Mother Theresa Effect is one. The insight being, when we address issues that affect vast numbers of people, it’s simultaneously ambiguous and overwhelming. But when we focus on an individual story, like you have done, it clicks psychologically and sparks empathy.

![]() .

.

That’s right. I agree.

.

Harlem at Four is also a history lesson. I learned a lot about the Father of Harlem. That’s a history I never learned, and your book opened a door for me. The first thing I did when I finished Harlem at Four was consult “the almighty Google” to see what else I could learn about him.

![]() .

.

And to that note… I wanted to have that glossary in the back, and my editor at Random House had the same idea. I’m a professor, so I believe in education. I wanted the book to be an educational resource for parents, and also for teachers.

You’re right, the book is aspirational in terms of its age range. It’s targeted at kids who are four to eight, but some information is a little older than that. And that’s on purpose. We wanted the kids to have an aspirational approach to the book.

We thought Frank Morrison’s images were so great that even a kid who didn’t know what Malcolm X was could figure out via the pictures. And with the glossary in the back, having his or her mother or father tell him or her about that information, it would all work out. So that was the idea behind the book’s back matter, the glossary about these people and places in Harlem.

Harlem is an interesting place. So many people who are important in Black history have been born there or had a major part of their life there. The glossary talks about Tupac Shakur, Afeni Shakur, all these people, Sonia Sanchez, Malcolm X. And if you didn’t know that, you wouldn’t know how important Harlem is.

I live in the lower east side in New York, but I’m in Harlem at least twice a week. I go to a writing workshop on Saturdays. Then on Wednesdays, I go to a café or bar in Harlem to write. And, you wouldn’t know how important that place is unless you knew some of this history.

.

We all need to know as much of the history of our country as possible. Otherwise, we get a myopic view of what the world should be. So, let’s turn the initial question on its head… what are the dangers of restricting or exempting these stories from the conversation?

![]() .

.

When people don’t know a nuanced history of a people, they tend to treat people in non-nuanced ways, as stereotypes. There are informational sources in America, be it the internet or certain types of news sources that put out an image, for example, of Black people that’s extremely negative.

Oftentimes folks who will hold anti-Black views don’t have anyone in their life, in a significant way, who are Black. They have almost no personal one-on-one experience with a Black person. Almost none, maybe someone who’s served their coffee, or at a café, or someone who is working for them or whatever. But as a peer, they don’t have that experience. So, if you restrict information that could offer a more nuanced, more replete understanding of Black people, what you’re doing is having non-Black people base their understanding of Black people on erroneous information.

I’m a professor. And I’m at a school where I teach mostly white kids – I’m at NYU. In my whole career, on the first day of class, I come early to class, I shake every student’s hand, and have a series of rituals. But on several occasions, students have walked into the class, seen me in the front of the class, and they’ve had an outburst. They’ve said, “You’re the professor?”

And this has happened several times. Because they don’t have experience with Black people, for example, in charge of them. A professor of record, a person with power over their grade, for example. Then they have an engagement with someone like me, whose a Black professor who has a Phd, but also from a very urban background. And I bring my full self into the classroom.

So, by the end of the semester – and this happens every semester – they’ve spent fifteen weeks with me in class, and they’ve had a very wide-ranging exposure to this one African-American man, who is complex and complicated, as everyone is.

What happens a lot in these course – because it’s a seminar and we do writing – eventually they begin to open up too. Because I do a pretty good job in the class, and they tend to like me in the class. They tend to befriend me, and come to office hours. And they will say, “Wow, I have to tell you, in my family people are pretty racist and say these things about Black people.”

And I will say to them, “I wonder how many Black people they’ve actually known in their lives. You’ve known me for fifteen weeks here (or whatever point it is in the semester), and you’ve got some real information, some data about a real person, not some stereotype, or some TV show.

So, the danger in banning books, like my book Harlem at Four, or any other book that deals with important topics around race, is that people who could read these books and gain a better understanding of, for example, the Black experience are robbed of that experience. And they’re basing their information on faulty information. As a result, there’s a continued tension in the country – divisiveness, conflict, and that’s bad for the country. That’s the negative externality of banning the book is that it’s bad for the country.

.

I absolutely agree with that. Banning books is bad for the country, for all the reasons you laid out.

The other thing I try to do on This Book is Banned revolves around how to read beyond plot. Because reading on that level is like the internet version of the subject at hand – lacking nuance. And, a significant number of the challenges, at least before book banning became so political, stemmed from a misreading of the book in question.

For example, people wanted to remove The Catcher in the Rye from classroom shelves and libraries because teenagers shouldn’t talk and behave like Holden Caulfield. But they failed to consider why the author might have written that character the way he did. What was Salinger actually saying by making those choices? If they had asked that simple question, “why,” it would be apparent that Salinger agreed with them, teenagers shouldn’t act like Holden Caulfield, that something is indeed very wrong here. So, what is the book actually about?

Given that you are the professor that you are, would you speak to that a little bit, the importance of reading beyond plot and surface narrative?

![]() .

.

I believe in the power of a good story. And, it’s really hard to tell a good story. Plot and story aren’t the same thing, but plot and story are related – I just want to say that. Some authors who write adult fiction, for example, will say “Well, I don’t really worry about the plot, just kind of get my ideas in there.” I think that’s a cop out for a writer who’s writing a novel not to make your story engaging enough. So there’s that.

I agree… for me, the best books are books that have a great story, have certain plot elements but also are trying to offer some insight into the human condition. How people love, how people get their hearts broken, how people have hope when there’s no reason to hope. How people survive tragedy and bounce back, say something about what it’s like to be alive on the planet. I think that’s what makes literature important.

And that’s why I was drawn to books. I really love to read. Although I’m a professor and I write books, I’m really a fan. I’m just a reader who happens to do other things. I really, really, really love to read. I could literally spend ten hours a day, seven days a week reading and never get tired. Never. I could do that and be very happy. I have other things I have to do, unfortunately. But I could do that and be very contend, reading ten hours a day every single day, seven days a week… I could do that and be totally happy.

Because when I’m reading, I’m learning, and I’m growing, and I’m having my mind stretched. I’m being challenged. I’m thinking about my own life, and about what it’s like to be human. So, I think that’s why it’s important to read beneath the story, to read beneath the plot. Because, when books are done well and are thoughtful, books can really be transformative.

Again, that’s my story. That year that I took those two electives, I still recall this, we read The Bluest Eye in one class. We read James Baldwin, we read Go Tell it On the Mountain, and Richard Wright. These are books I hadn’t read before, and I was so blown away. I was like, “Oh my God, this is incredible.” You know? I recall calling my mother and saying, “Ma, there’s been a change in the master plan.”

So, that’s why I think we need to read beneath the surface, because there’s so much there.

.

There is so much there. And, it can be about experiences you’ll never have in your own life, so it can bridge the divisiveness. You’re absolutely right, it has to be a good story to draw you in, but there’s so much more to it than that. It’s like the proverbial iceberg, the bulk of it’s under the surface.

![]() .

.

That’s right.

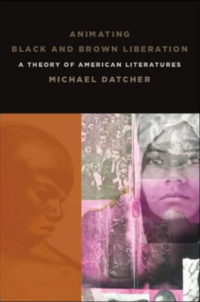

I also picked up your book, Liberating Black and Brown Liberation. And, returning to your point about the students who come into your class and have never had a Black professor before… I can relate, having grown up in a homogenous environment myself. And that experience was the most significant part of my education, a world-view-changing realization about what the real world looks like and how I fit into it.

![]() .

.

Yeah, experience matters. As African-Americans, because we live in a world that’s run by folks who don’t look like us, we have to… [For example] as a professor, my training is literary theory, so I know all the French theorists, I know all the German theorists. And, I do American Literature so I know all the great American books. That’s part of my job, and I like those books, actually. Those are great books.

And, as someone who’s Black, I’m interested in stories that deal with Black subject matter… people of color. The book that you raised a second ago, that book deals with Black and brown people, Black and Latinx individuals. So, I also know a great deal about Latin literature as well. I want to be conversant in stories that deal with black and brown people as well.

So, we always have these two jobs. I have to know all the “white stuff,” basically, the dominant group stuff. Because that’s part of the job, which again, I like those books – there’s a lot of good literature. I like theory. I’m a fan. But I also want to understand my own history, culture, and think about how theory can engage ideas by Black thinkers and deal with the Black experience.

The book that you mentioned is all about that. It’s me using my academic training, applying those techniques, those ideas to books by Black and brown writers. And trying to think through how we can more fairly adjudicate the value of a work of literature.

Because in my field, the authors who are famous, who are respected, are so because critics write about them, and they deify certain people. And, frankly, some of the folks who are deified don’t deserve to be deified – as much. But, it’s because the folks who are deifying them are from that experience. Whereas, African-American writers may come forward and write these great books, and their books are not – in my opinion – fairly adjudicated and they’re not as respected.

So, in terms of being in the canon, The Norton Anthologies and all the other important anthologies, there’s very, very few of the many, many great Black writers, for example. Because the authorities, the gatekeepers, don’t have that shared experience.

In the American canon of literature, one requirement is that the book has to be universal. But really, universal is kind of a misnomer for the interests, concerns, ideas, likes of white men. And then you stack universal on top of that. That’s what it really, really is. If you don’t fit in that narrow box, your work isn’t universal.

So, Liberating Black and Brown Liberation is about challenging that idea of universality, and kind of get at, “let’s talk about what’s really universal.”

I could go on all day. Because this is all important to me.

.

And it is all important. In addition to the question of book banning – what’s going with K-12 curriculums and public libraries – is the question of how to read literature, as well as which books get presented in arenas that matter. They’re all part of why it’s important for stories about diversity to not only be told, but be heard and acknowledged. Because these books are no less universal than anything else in American canon… they’re still about human experience and people making their way in the world.

Thank you for your time. This has been fabulous.

![]() .

.

And thanks for your service and your work about banned books. We need it.

Be sure to see what the other authors in our Power of Books Series

have to say about the importance of books:

Jamie Jo Hoang,

author of My Father the Panda Killer

Edward Underhill,

author of Always the Almost,

and This Day Changes Everything

Ryan Estrada,

co-author of Banned Book Club,

and Occulted

.

#Power of Books Author Series #Dr. Michael Datcher #Black History Month #Harlem Renaissance #the art of reading

Endnotes:

[1] Bruinius, Harry. “Banning Books: Protecting kids or erasing humanity?” October 6, 2023. The Christian Science Monitor. https://www.csmonitor.com/USA/Society/2023/1006/Banning-books-Protecting-kids-or-erasing-humanity

Rado, Diane. “In 2024, more censorship and bans: FL, TX removing large batches of books in public schools.” December 21, 2023. News From The States. https://www.newsfromthestates.com/article/2024-more-censorship-and-bans-fl-tx-removing-large-batches-books-public-schools

Unite Against Banned Books 2023 Censorship Numbers.

Images:

Power of Books: Photo by Glenn Carstens-Peters on Unsplash Edited: Added Power of Books Author Series text.

Dr. Michael Datcher: michaeldatcher.com

Cover of Harlem at Four: Datcher, Michael. Harlem at Four. New York: Random House, 2023.

Cover of Animating Black and Brown Liberation: Datcher, Michael. Animating Black and Brown Liberation: A Theory of American Literatures. Albany: State University of New York, 2019.