I had thought America was against totalitarianisms. If so, surely it is important for young people to be able to recognize the signs of them. One of those signs is book-banning. Need I say more? ~ Margaret Atwood [1]

F

F

ollowing the Supreme Court’s recent overturn of Rowe v Wade, Margaret Atwood’s book The Handmaid’s Tale has understandably become the face of activism for reproductive rights. But The Handmaid’s Tale wasn’t intended to be a feminist commentary on the control of women and their reproductive capacities.

Rather, it’s a study in totalitarian systems of government. Atwood’s foundational question?

If you wanted to seize power in the United states, abolish liberal democracy, and set up a dictatorship, how would you go about it? [2]

As Atwood’s quote at the opening of this piece points out, banning books is an early indicator of creeping totalitarianism. And, the number of books being banned in the United States has skyrocketed in the last few years.

Bearing Handmaid’s use as a protest symbol for reproductive rights in mind, it’s easy to overlook the significance that Gilead’s prohibition of women to read plays in establishing and maintaining its totalitarian control.

As one of Gilead’s hardliners put it:

Our big mistake was teaching them to read. We won’t do that again. [3]

The Testaments, Atwood’s follow-up work to The Handmaid’s Tale, reveals how Gilead falls. And once again, reading and access to information looms large. Atwood’s combined works gives us insight into the role that reading and access to information can play in holding the line against totalitarianism in the good ol’ U.S. of A.

Whoever Controls The Word Maintains Power

Within both novels, Atwood makes it abundantly clear that whoever controls the word maintains power. And what better way to symbolize this reality than to put the headquarters of Gilead’s enforcer unit, The Eyes, in what was once a library? This “former grand library”:

…now shelters no books but their own, the original contents having been either burned or, if valuable, added to the private collections of various sticky-fingered Commanders. [4]

The combined works serve as a reminder that learning to read has been carefully controlled throughout history. Who is allowed to. Who isn’t. And more insidiously, whose stories can and cannot be told. [5]

The narrator of The Handmaid’s Tale tells her story rather than writing it down because, as she notes, she has nothing to write with. And even if she did, writing is forbidden anyway. Gilead enforces its mandate against women reading and writing with a “three strikes” policy. On the third conviction they cut off your hand.

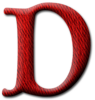

Though no one has suggested lopping off body parts as punishment for reading banned books in the U.S., teachers and librarians have been threatened with time behind bars for providing books like The Catcher in the Rye, The House on Mango Street, and Speak to students.[6]

Controlling whose stories can and cannot be told should sound especially familiar. Because these days, books that tell stories about people of color, those that revolve around LGBTQ+ individuals, or include characters from non-Christian backgrounds are being purged from classroom shelves and school libraries at an alarming rate.

And, when marginalized communities such as these are not represented in the books students read, it’s clear they’re intentionally being made invisible, stripped of their humanity, and therefore rendered powerless. Just like Atwood’s narrator, whose real name we don’t know because using it is forbidden.

We only know her as Offred, a name designed to eliminate her personhood, one composed of the possessive preposition “of” and the first name of the Commander she is currently assigned to. Offred tries to tell herself that this dehumanizing tactic doesn’t matter – like those who dismiss the omission of diverse communities in school curriculums as inconsequential… “but what I tell myself is wrong,” Offred reflects, “it does matter.” [7]

Just like it matters that particular communities within our country are being made invisible. That is also wrong.

Fascism Erases History

One of the most effective ways of controlling the word and consolidating power is to erase history. And, as scholar of totalitarian systems Jason Stanley points out, that’s just what authoritarian regimes do. They find ways of erasing or concealing history, which allows them to misrepresent history as a single story.[8]

Consistent with this observation, Offred talks about book-burnings that took place across Gilead because:

the corrupt and blood-smeared fingerprints of the past must be wiped away to create a clean space for the morally pure generation that is surely about to arrive. [9]

Aunt Lydia is one of the women in charge of what Atwood describes as brainwashing new handmaids in a sort of Red Guard re-education facility known as the Red Center.[10] Lydia refers to the initial group of conscripted handmaids as a “transitional generation.”[11]

And, the reason they’re a transitional generation is that the “training process,” as it were, will be easier for the next cohort of handmaids. Because, as Aunt Lydia notes, they “will accept their duties with willing hearts.”[12] What Aunt Lydia doesn’t say, however, is that the next generation of handmaids will accept their duties willingly “because they will have no memories of any other way.”[13]

When authoritarian regimes set out to erase history, as Stanley further states, they do so through education, by purging certain narratives from school curriculums.[14] Gilead accomplished this by replacing girls’ academic curriculum with “domestic education,” which revolves around subjects like embroidery, elementary gardening, the making of paper flowers, skills deemed suitable hobbies for future Wives of Commanders.[15]

They were also taught “how to judge the quality of the food that was cooked for us and served at our table.”[16] What they weren’t taught, however, is how to read or write.

Reading and writing may not have been expunged from American schools, but as touched upon above, huge swaths of our history have been purged from the school curriculums in a number of states. Not to mention the recent dismantling of The Department of Education.

Educators at all levels are targeted, and any teaching that addresses racial hierarchy, patriarchy, or heteronormativity is being suppressed. Histories of political movements like Black Lives Matter are also being removed from social studies curriculums.

By eliminating the history of uprisings against the status quo, authoritarians give students the idea that the status quo has never been – and can never be – challenged.[17]

Lack Of Information

Is Part Of The Nightmare

It goes without saying that not knowing what happened to her family at the hands of Gilead authorities during their attempted escape into Canada wears on Offred’s psyche. But, it’s significant that she also talks about a sense of deterioration, specifically the diminished skills that result from Gilead’s edict against women reading and writing.

Her Commander begins requesting that she visit him in his office alone. As it turns out, he’s not after kinky sex, but to watch her read books and magazines that he’s appropriated from pre-Gilead times… and to play Scrabble.

In describing these illicit meetings, Offred compares Gilead’s prohibition of reading to the deprivation of food:

On these occasions I read quickly, voraciously, almost skimming, trying to get as much into my head as possible before the next long starvation. If it were eating it would be the gluttony of the famished. [18]

But even worse, as she and the Commander play this quintessential game of words, she notes how her reading and writing skills have deteriorated:

My tongue felt thick with the effort of spelling. It was like using a language I’d once known but had nearly forgotten… It was like trying to walk without crutches, like those phony scenes in old TV movies. You can do it. I know you can. That was the way my mind lurched and stumbled, among the sharp r’s and t’s, sliding over the ovoid vowels as if on pebbles. [19]

A comparable situation is taking place related to reading achievement in America. Reading scores on the most recent (2024) National Assessment of Education Progress (known as America’s report card) fell two points below 2022’s historic low. “We’re still recovering from the pandemic,” you may say. And, there is truth to that statement.

However, as Peggy Carr, commissioner of the National Center for Education Statistics, points out, this concern “cannot be blamed solely on the pandemic.”[20] The fact that math scores have not dropped among 8th graders, and have actually improved among 4th graders indicate something else is going on.

Recent studies have found that the surge in book banning has negatively affected reading skills. Yes, we’re still recovering from the pandemic. But educators now have fewer resources at their disposal to aid in this recovery. And the types of books hardest hit by these bans are the ones that have the greatest positive impact on reading achievement.

Results from The Early Childhood Longitudinal Study reveal that “social studies is the only subject with a clear, positive, and statistically significant effect on reading improvement.”[21] Social Studies is defined as:

the study of individuals, communities, systems, and their interactions across time and place that prepares students for local, national, and global civic life. [22]

And it’s precisely these types of books, those about diverse characters and life experiences, as well as books addressing difficult historical truths that are being banned from America’s classrooms and libraries – much to the detriment of students’ reading achievement.

Social And Political Dimensions

Of The Ability To Read

Atwood’s works also speak to the social, and political dimensions of the ability to read. She specifically focuses on oppression enforced by the institutional control of acquiring knowledge and information.

For example. Aunts are allowed to read and write, because they’re in charge of Handmaids’ assignments and maintaining bloodlines. And, Aunt Lydia employs this hierarchical distinction as a show of power, rubbing the handmaids’ proverbial noses in it, frequently making them watch and wait as she reads silently “flaunting her prerogative.” [23]

Commanders’ offices are lined with books. As suggested above, they like to accumulate books, gloat over the collections they’ve compiled, and boast about what they’ve pilfered. [24]

And, the Bible is kept under lock and key. This mandate is significant because Gilead is ostensibly founded on biblical concepts. Commanders can read from the Bible to their primarily female households, but the women are forbidden to read it for themselves. [25]

Needless to say, the Commanders cherry-pick passages and spin them in a way that supports Gilead’s totalitarian agenda. And, given that the source of these passages is denied them, women have no way of refuting these intentional misreadings.

The Power Of Storytelling

The Handmaid’s Tale is undoubtedly about oppression and control. However, it’s also about the power of narrative. Atwood does indeed focus on oppression enforced by institutional control of knowledge and information. But, she also examines the self-liberating capacity of storytelling. [26]

The Aunts at the Red Center did their best to brainwash the woman who would come to narrate The Handmaid’s Tale. They set out to crush her identity and demolish her sense of individuality. Yet, she manages to record her feelings, experiences, thoughts, and memories.

That’s because, as Jason Stanley observes:

Authoritarians cannot erase people’s lived experiences, and their legacies written into the bones of generations. In this simple fact lies always the possibility of reclaiming lost perspectives. [27]

By telling her own story throughout the novel, Offred reclaims her sense of self and reconstructs the subjectivity they literally tried to beat out of her at The Red Center. In short, she recovers the voice Gilead has denied her.

In doing so, she recreates erased histories and uncovers versions of events that Gilead had repressed. [28]

Most importantly, by sharing her tale she becomes a social agent – and, as a result of the power of narrative, aids in Gilead’s eventual downfall.

When only 11 people are responsible for 60% of book challenges in the U.S. (as has recently been the case), the vast majority of us are being denied a voice – in this case about which books our kids are allowed to read. [29] To say nothing of the voices within the marginalized communities whose stories are being banned, voices that allow us to understand and relate to those whose lives are different than our own.

Since only a handful of individuals are responsible for over half of the book challenges in this country, they’re the ones determining whose histories are being erased. And, without consulting the rest of us, they’re repressing information about landmark events like the Stonewall uprising, not to mention the institution of slavery and its role in our country.

Reclaim your voice. Make sure stories like these continue to be told. Narrative has the power to break down the “us vs them” environment authoritarian regimes thrive on. [30]

A Trio Of Narratives

Like The Handmaid’s Tale, Atwood’s follow up work is a meta-narrative about storytelling, one emphasizing the importance of testimony and witnessing. The Testaments is divided into a trio of interwoven narratives: One is Aunt Lydia’s, which is written illegally in blue ink and unironically hidden inside a copy of Cardinal Newman’s Apologia Pro Vita Sua: A Defense of One’s Own Life.

The second is the recorded testimony of a young woman named Agnes, about growing up in The Republic of Gilead. And third, is the recorded testimony of Daisy, a teenage girl who grew up in Canada, and can’t help but feel that her parents are keeping something from her.

The motif of reading and writing is emphasized toward the end of Atwood’s novel as if to highlight its role in the fall of Gilead.

As noted above, Aunt Lydia is the keeper of Gilead’s bloodlines. She’s also the clandestine chronicler of its “secret histories.”[31] Aunt Lydia is not entirely what she seems. And, she’s well aware that knowledge is power. Especially the aspect Henry Ward Beecher pointed out, that knowledge is “powder also, liable to blow false institutions to atoms.” [32]

Agnes doesn’t learn to read until she commits to becoming an aunt. And, she chose this path in order to save herself from being married to an old and powerful Commander with a track record of young wives who die from mysterious illnesses. But even then, she continues to accept what she’s been taught about Gilead and her subservient place in it.

The day finally comes, however, when Agnes is granted full access to the Bible.

And, after reading a story she’s been told over-and-over in school for herself, Agnes discovers that she and all the other girls have been lied to about what the passages say. She sees that the meanings of the stories have been twisted to keep women obedient, subservient, and willing to sacrifice themselves to the patriarchy. Agnes tells us that:

Up until that time I had not seriously doubted the rightness and especially the truthfulness of Gilead’s theology. If I’d failed at perfection, I’d concluded that the fault was mine. But as I discovered what had been changed by Gilead, what had been added, and what had been omitted, I feared I might lose my faith. [33]

Agnes has come to realize “everyone at the top of Gilead has lied to us,” and that, as is typical of authoritarian regimes,:

Bearing false witness was not the exception, it was common. Beneath its outer show of virtue and purity, Gilead was rotting. [34]

Sometime later, Agnes comes face-to-face with another startling revelation. She discovers that her birth mother is a runaway handmaid suspected of working with the resistance in Canada. Consistent with Jordan Stanley’s observation about life experiences being etched in our bones, this information triggers the memory of when Agnes was torn from her mother’s arms as they were running through the forest in an attempt to escape Gilead.

The Gilead wife who raised Agnes transformed this harrowing experience into a nightly fairy tale about how they had been running through the forest after she rescued Agnes from a wicked witch. [35] Agnes puts two-and-two together, as the saying goes. She realizes that, like the Bible passages fed to her on a daily basis, her own story had been twisted for Gilead’s purposes.

The kicker is… that the document Agnes is now able to read – one that only Aunt Lydia could have slipped onto her desk – reveals that her mother had a second child, one who had been smuggled into Canada as an infant. And, that child is Baby Nicole.

Baby Nicole has become a propaganda tool for the people of Gilead to rally around:

Baby Nicole, whom we prayed for on every solemn occasion at Ardua Hall [where Aunts are trained]. Baby Nicole, whose sunny cherubic face appeared on Gilead television so often as a symbol of the unfairness being shown to Gilead on the international stage. Baby Nicole, who was practically a saint and martyr, and was certainly an icon. [36]

When Agnes discovers that Baby Nicole is her sister, the proverbial lightbulb flickers on, and she begins to comprehend “the deplorable degree of corruption” within the totalitarian regime that has taken over the United States of America. [37] Any blind obedience she may have felt to The Republic of Gilead is stripped away. She comes to understand that, if the country she loves is to be saved, action must be taken to bring Gilead in line with what it purports to stand for.

At this point, it should be apparent that the source of the third testimony, the Canadian teenager named Daisy, is none other than Baby Nicole. Significantly, Atwood chose the name Nicole because it means “Victory of the people.” [38] And she is, indeed, the lynchpin in events that lead to Gilead’s fall.

The Testaments Is Defined By Action

While The Handmaid’s Tale is about Offred’s powerlessness and passivity, The Testaments revolves around action. As established above, this action is born of the ability to read and have access to information. And, it’s prompted by revealed deceptions and restored history.

It should come as no surprise that this regime-ending action revolves around Aunt Lydia, Agnes, and Daisy/Baby Nicole. Or that, as in many other works about the fall of totalitarian regimes, resistance organizations, undercover operatives, and the exposure of sensitive secrets are all involved.

Needless to say, Henry Ward Beecher was right, knowledge is explosive – when information about the multitude of crimes among Gilead’s top brass was released, this authoritarian regime begins to crumble. In true totalitarian fashion, what was left of Gilead still tried to control the word. They insisted that the repressed information Aunt Lydia had been compiling which was being released by Canadian media, was all “fake news.” [39]

Despite Aunt Lydia’s role in perpetuating Gilead’s abuse – or perhaps because of it – there’s a lesson we can learn from her. At the close of her hand-written manuscript, she addresses a future reader, acknowledging the possibilities for what will become of the pages she’s written.

The prospects are consistent with the way we currently treat works of literature. We’ll either view them as a treasure, “to be opened with utmost care.” Or we’ll tear them apart, maybe burn them, as Lydia notes, “that often happens to words.” [40]

This future reader may also read Aunt Lydia’s testimony, wondering how she could have “behaved so badly, so cruelly, so stupidly,” and she wouldn’t be astonished if that is the case. [41] What Aunt Lydia hopes, however, is that the future reader will be a student of history, and:

Make something useful of [Aunt Lydia]: a warts-and-all portrait, a definitive account of [her] life and times, suitably footnoted. [42]

Aunt Lydia’s lesson is that she advocates for a complete and accurate history to be told about Gilead, even though it comes at her expense. Regrettably, book banners in the U.S. restrict information about the hard truths in American history rather than make something useful of them.

We all have a choice to make when it comes to book banning and the creeping totalitarianism it indicates. It’s the same choice Offred faced as she contemplated the message carved in the closet by the handmaid assigned to this Commander before her:

I could just sit here, peacefully. I could withdraw. It’s possible to go so far in, so far down and back, they could never get you out.

Nolite te bastardes carborundorum. [Which means don’t let the bastards grind you down.] Fat lot of good it did her.

Why fight? [43]

Offred’s answer after considering the possibility of not fighting… “That will never do.” [44]

Row! Row For Your Life!

Margaret Atwood used the following quote from Ursula K Le Guin as an epigram for The Testaments. It picks up where Offred’s contemplation above leaves off:

Freedom is a heavy load, a great and strange burden for the spirit to undertake. It is not easy. It is not a gift given, but a choice made, and the choice may be a hard one. [45]

Le Guin’s quote is embodied in the last leg of the clandestine operation that ultimately brings Gilead down. Agnes and Nicole are in a rowboat, struggling to make it to the shore where resistance operators are expecting them. Given that the tide is against them, Agnes is understandably worried that they’re so far out they’ll be swept away.

Their situation functions as a metaphor for a nation being swept away by creeping totalitarianism. And, Nicole’s response to Agnes sums things up perfectly:

No we won’t. Not if you try. Now, go! And, go! That’s it! Go! Go! Go!… Row! Row for your life! [46]

It goes without saying that the two make it to shore and are scooped up by the resistance agents waiting there. The cache of information they are carrying is successfully delivered. And the rest as they say is history, one that is complete, accurate, and available to learn from.

Atwood’s addition of “Historical Notes” is an optimistic indication that Gilead did indeed fall. But, it’s also a cautionary tale. Because Professor Pieixoto’s misogynistic remarks make it abundantly clear that the seeds of what spawned Gilead are still present, and that the fight to keep it at bay is ongoing and constant.

And, that doesn’t simply apply to women’s issues, or to the fictional Republic of Gilead. It applies to democracy generally. So, don’t let book banning keep you or your student from reading books that help us understand our history, the people in our community, or how our government is intended to work.

Make sure stories like these get told. Knowing our history and understanding those whose lives are different than our own has the power to break down the “us vs them” environment authoritarian regimes thrive on. [47] And if we know how our government is intended to work, we can see when its institutions are being disregarded or dismantled for authoritarian purposes.

As Senator Cory Booker urges us:

Don’t let your inability to do everything undermine your determination to do something. Progress starts with a single step forward. [48]

So, fire up family reading nights and feature banned books. Visit the public library with your student and check out the books your district has removed from its curriculums or library shelves. Organize a banned book club for your teens.

Heed Nicole’s call to action, “Row. Row for your life!” Which in this case means, Read, Read, Read! As Henry Ward Beecher told us, and Margaret Atwood has shown us, knowledge is power… to keep freedom alive and our democracy strong, or to blow false, authoritarian regimes to atoms — whichever one is called for.

.

That’s my take on The Handmaid’s Tale — What’s yours?

Check out this Discussion Guide to get you started.

.

And, here are a couple of resources for

learning about American history:

Share This Post, Choose a Platform!

Endnotes:

[1] Taneja, Sehr. “These Were the Most Commonly Banned Books in America in 2021.” Katie Couric Media. August 12, 2022.

https://katiecouric.com/entertainment/book-guide/most-banned-books-america/

[2] Bickford, Donna M. Understanding Margaret Atwood. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press, 2023. Pg 24.

[3] Atwood, Margaret. The Handmaid’s Tale. New York: Vintage Books, 1998. Pg 307.

[4] Atwood, Margaret. The Testaments. New York: Vintage Books, 2019. Pg 64.

[5] Thomas, P. L. “Margaret Atwood’s The Testaments: Reading and Writing Beyond Gilead.” Radical Scholarship.com https://radicalscholarship.com/2019/10/07/margaret-atwoods-the-testaments-reading-and-writing-beyond-gilead/

[6] Missouri House Bill No. 2044. https://house.mo.gov/billtracking/bills201/hlrbillspdf/4634H.01I.pdf

[7] Atwood, Margaret. The Handmaid’s Tale. New York: Vintage Books, 1998. Pg 84.

[8] Stanley, Jason. Erasing History: How Fascists Rewrite the Past to Control the Future. New York: One Signal Publishers, 2024. Pg xi-xii.

[9] Atwood, Margaret. The Testaments. New York: Vintage Books, 2019. Pg 14.

[10] Renfro, Kim. “Margaret Atwood has a small but violent cameo in ‘the Handmaid’s Tale’ premiere.” Business Insider. April 27, 2017. https://www.businessinsider.com/handmaids-tale-margaret-atwood-cameo-pilot-2017-4?op=1

[11] Atwood, Margaret. The Handmaid’s Tale. New York: Vintage Books, 1998. Pg 117.

[12] Atwood, Margaret. The Handmaid’s Tale. New York: Vintage Books, 1998. Pg 117.

[13] Atwood, Margaret. The Handmaid’s Tale. New York: Vintage Books, 1998. Pg 117.

[14] Stanley, Jason. Erasing History: How Fascists Rewrite the Past to Control the Future. New York: One Signal Publishers, 2024. Pg xii.

[15] Atwood, Margaret. The Testaments. New York: Vintage Books, 2019. Pg 19, 154.

[16] Atwood, Margaret. The Testaments. New York: Vintage Books, 2019. Pg 154.

[17] Stanley, Jason. Erasing History: How Fascists Rewrite the Past to Control the Future. New York: One Signal Publishers, 2024. Pg xx-xxi.

[18] Atwood, Margaret. The Handmaid’s Tale. New York: Vintage Books, 1998. Pg 184

[19] Atwood, Margaret. The Handmaid’s Tale. New York: Vintage Books, 1998. Pg 155-156.

[20] Schwartz, Sarah. Reading Scores Fall to New Low on NAEP, Fueled by Declines for Struggling Students. January 29, 2025. EducationWeek.

https://www.edweek.org/leadership/reading-scores-fall-to-new-low-on-naep-fueled-by-declines-for-struggling-students/2025/01

[21] Adam Tyner and Sarah Kabourek. Social Education 85 (1), pp 32-39.

[22] National Council for the Social Studies. https://www.socialstudies.org/about/definition-social-studies

[23] Atwood, Margaret. The Handmaid’s Tale. New York: Vintage Books, 1998. Pg 275.

[24] Atwood, Margaret. The Testaments. New York: Vintage Books, 2019. Pg 282.

[25] Atwood, Margaret. The Handmaid’s Tale. New York: Vintage Books, 1998. Pg 89.

[26] Bickford, Donna M. Understanding Margaret Atwood. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press, 2023. Pg 24.

David S. Hogsette (1997) Margaret Atwood’s Rhetorical Epilogue in The Handmaid’s Tale: The Reader’s Role in Empowering Offred’s Speech Act, Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction, 38:4, 262-278. Pg 263.

[27] Stanley, Jason. Erasing History: How Fascists Rewrite the Past to Control the Future. New York: One Signal Publishers, 2024. Pg xii.

[28] Bickford, Donna M. Understanding Margaret Atwood. Columbia, South Carolina:The University of South Carolina Press, 2023. Pg 25

David S. Hogsette (1997) Margaret Atwood’s Rhetorical Epilogue in The Handmaid’s Tale: The Reader’s Role in Empowering Offred’s Speech Act, Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction, 38:4, 262-278. Pg 264.

[29 ]Natanson, Hannah. “Objections to sexual, LGBT, content propels spike in book challenges.” The Washington Post. June 9, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2023/05/23/lgbtq-book-ban-challengers/

[30] Stanley, Jason. How Fascism Works: The Politics of Us and Them. New York: Random House, 2020.

[31] Atwood, Margaret. The Testaments. New York: Vintage Books, 2019. Pg 39.

[32] Beecher, Henry Ward. “Anti-Slavery Lectures,” The New York Times, January 17, 1855.

https://www.nytimes.com/1855/01/17/archives/antislavery-lectures.html

[33] Atwood, Margaret. The Testaments. New York: Vintage Books, 2019. Pg 272.

[34] Atwood, Margaret. The Testaments. New York: Vintage Books, 2019. Pg 276.

[35] Atwood, Margaret. The Testaments. New York: Vintage Books, 2019. Pg 19.

[36] Atwood, Margaret. The Testaments. New York: Vintage Books, 2019. Pg 295.

[37] Atwood, Margaret. The Testaments. New York: Vintage Books, 2019. Pg 301

[38] Gilbert, Sophie. “The Challenge of Margaret Atwood.” The Atlantic. September 5, 2019.

[39] Atwood, Margaret. The Testaments. New York: Vintage Books, 2019. Pg 349

[40] Atwood, Margaret. The Testaments. New York: Vintage Books, 2019. Pg 355

[41] Atwood, Margaret. The Testaments. New York: Vintage Books, 2019. Pg 355

[42] Atwood, Margaret. The Testaments. New York: Vintage Books, 2019. Pg 355

[43] Atwood, Margaret. The Handmaid’s Tale. New York: Vintage Books, 1998. Pg 225

[44] Atwood, Margaret. The Handmaid’s Tale. New York: Vintage Books, 1998. Pg 225

[45] Le Guin, Ursula. In Margaret Atwood’s The Testaments. New York: Vintage Books, 2019. Pg 11.

[46] Atwood, Margaret. The Testaments. New York: Vintage Books, 2019. Pg 340

[47] Stanley, Jason. How Fascism Works: The Politics of Us and Them. New York: Random House, 2020.

[48] Senator Cory Booker. Facebook. October 21, 2020.

Images:

Whoever controls the word maintains power: Photo by Biao Yu on Unsplash

Fascism erases history: Photo by Tim Mossholder on Unsplash

Lack of information is part of the nightmare: Photo by Valentin Fernandez on Unsplash

Social and political dimensions of the ability to read: Photo by Artem Balashevsky on Unsplash

The power of storytelling: Photo by Brett Jordan on Unsplash

A trio of narratives: Photo by Jametlene Reskp on Unsplash

The Testaments is defined by action: Original photo by unknown author. Reproduction from public documentation/memorial by Lear 21 at English Wikipedia. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, 2.5 Generic, 2.0 Generic and 1.0 Generic license.

In conclusion: Photo by The New York Public Library on Unsplash

![]() J

J

L

L

M

M