I

I

magine if you will, living in a world where you never see yourself represented in books or media. (Insert Twilight Zone theme song here). And, when you finally do, it’s as negative, immoral, or downright evil. How would that effect you? And what does it have to do with ThePicture of Dorian Gray?

Consider this… LGBTQIA youth are more than four times as likely to attempt suicide than their straight cisgendered peers. Not because LGBTQIA individuals are inherently prone to suicide risk – they aren’t. Being stigmatized by society is what places LGBTQIA individuals, like mathematician and early computer genius Alan Turing, at a higher risk for suicide.[1]

Oscar Wilde’s 1890 novel The Picture of Dorian Gray is the story of this unfortunate reality. And, Dorian’s portrait is a roadmap of psychological damage resulting from societal stigma, rather than one of sinful debauchery as it is traditionally viewed.

The Picture of Dorian Gray revolves around a triumvirate of core characters who collectively represent the experience of a single individual. Wilde tells us this himself, when he wrote the following in a letter to an admirer of his writings regarding Wilde’s relation to the characters in The Picture of Dorian Gray:

Basil Hallward is what I think I am;

Lord Henry what the world thinks me;

Dorian is what I would like to be in other ages, perhaps.[2]

You see… Wilde was among those who participated in London’s gay subculture. Like many of these men, he led a secret double life. Having experienced it firsthand, Wilde knew what it’s like to try to navigate an intolerant society.

Each of Dorian Gray’s core characters embodies an aspect of what it’s like for LGBTQIA individuals who live in a repressive, anti-LBTQIA society… or as Wilde put it, “a harsh, uncomely Puritanism.”[3] And, Basil Hallward’s painting of Dorian Gray reflects the erosion of psychological and emotional well-being caused by living in such corrosive circumstances – an experience that all too often ends in suicide.

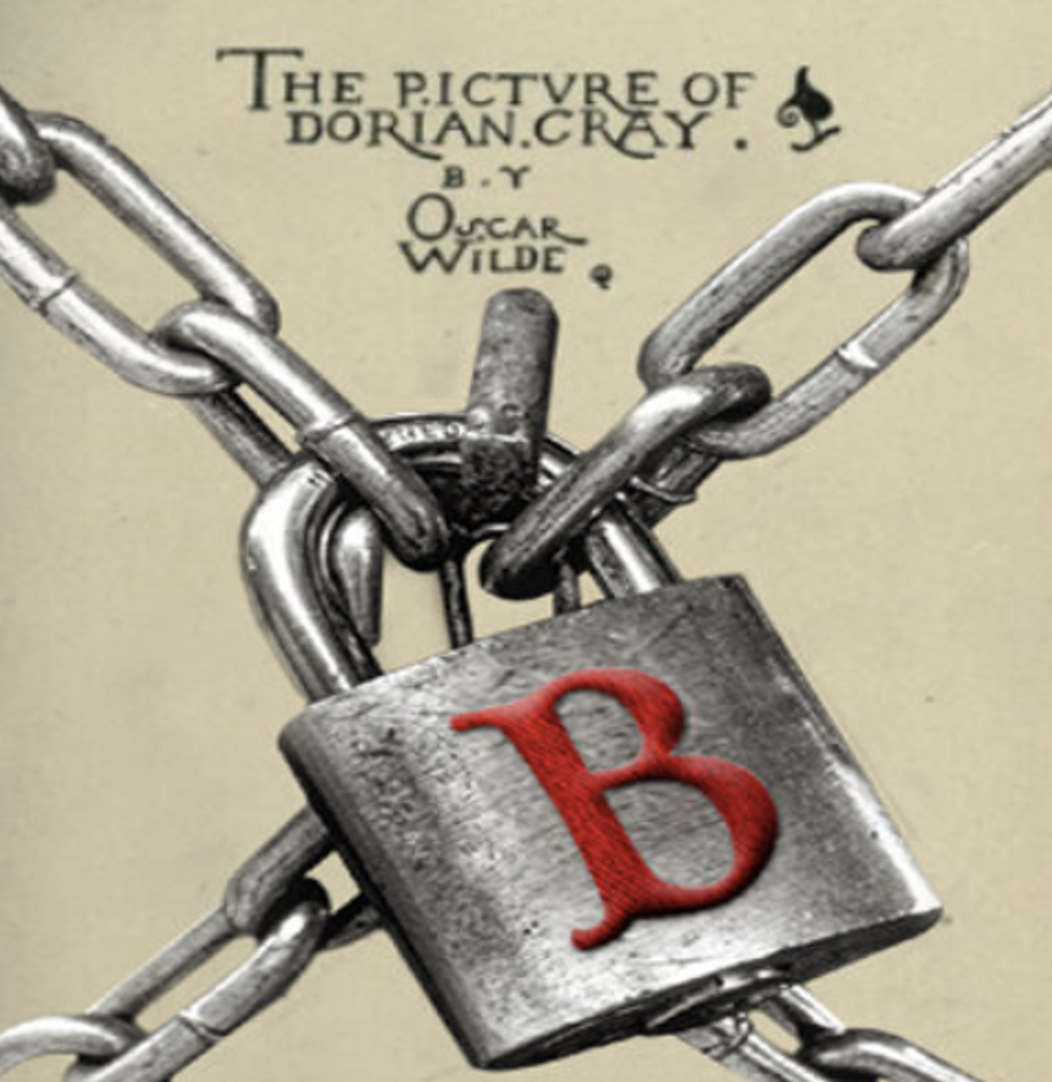

The Picture of Dorian Gray

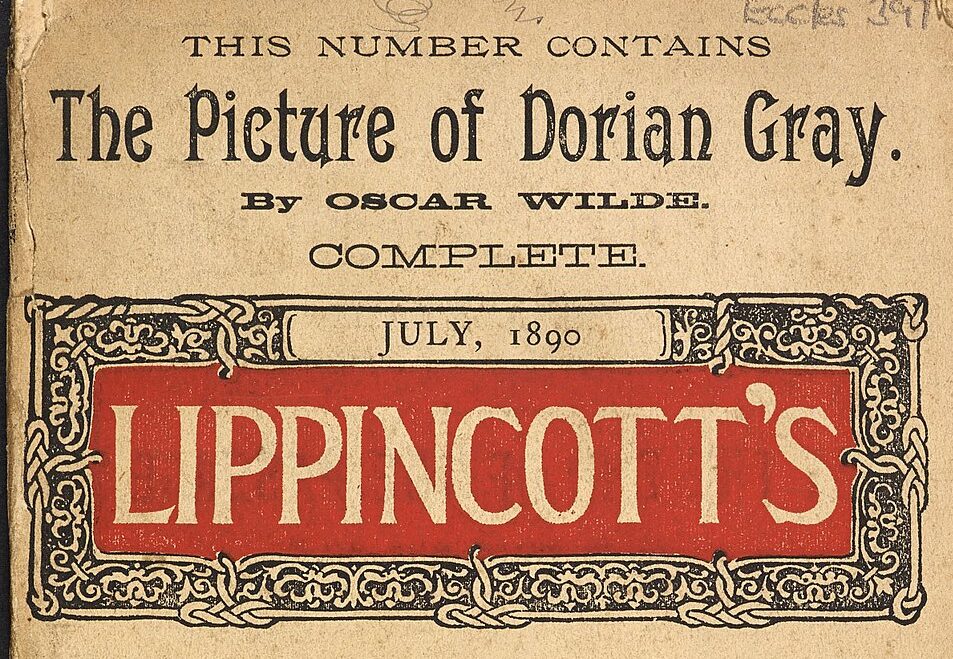

Ccontroversial From The Start

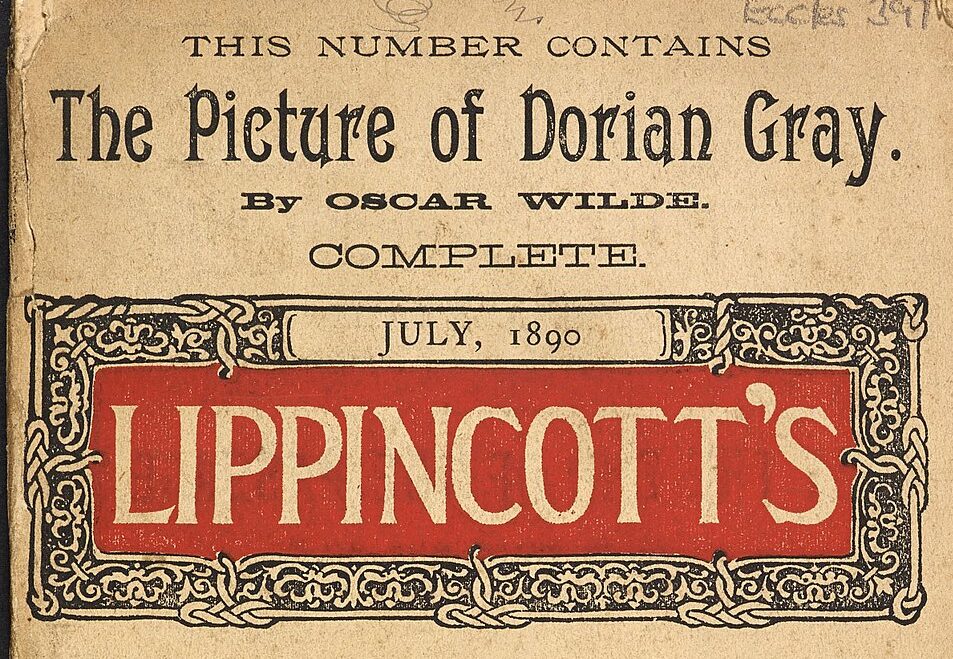

The Picture of Dorian Gray comes closer than any other mainstream English novel of its time to treating same gender sexuality in an overt fashion. And, as this scathing review indicates, when the first installment of this serialized work appeared in Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine (July, 1890), it was immediately controversial, and continues to be commonly banned: [4]

Mr. Oscar Wilde has again been writing stuff that were better unwritten; and while The Picture of Dorian Gray, which he contributes to Lippincott’s, is ingenious, interesting, full of cleverness, plainly the work of a man of letters, it is false art – for its interest is medico-legal; it is false to human nature – for its hero is a devil; it is false to morality – for it is not made sufficiently clear that the writer does not prefer a course of unnatural iniquity to a life of cleanliness, health, and sanity.[5]

Reviews in leading magazines the Scots Observer and the St. James’s Gazette suggested Wilde should be prosecuted for what he had written. And W. H. Smith & Son, Britain’s largest bookseller, pulled the July issue of Lippincott’s from its railway bookstalls.[6]

And this was after Lippincott’s editor struck nearly 500 words from Wilde’s original transcript, material which made the sexual nature of Basil’s feelings for Dorian Gray even more vivid and clear.

In response to this backlash, Wilde further edited his manuscript in an effort to appease the public. A guy has to make a living after all, and this reaction to his work put that at risk. To say nothing of getting on The National Vigilance Association’s radar (which is precisely the social purity organization it sounds like it is).[7]

The fact that The Picture of Dorian Gray was used as evidence against Wilde in his trial for “gross indecency,” underscores just how incendiary it was. Wilde was charged under the eleventh amendment of the 1885 Criminal Law Amendment Act, which created the new offense of gross indecency, criminalizing all sexual activity between men. He was sentenced to two years hard labor, the most extreme sentence possible under the law.[8]

Terms Like

“Sexual Orientation”

Didn’t Exist

Victorian Society saw same gender sexuality as an unclean and “deviant” vice rather than as an orientation or identity. [9] Consequently, Victorians lacked the language relating to same gender sexuality that has since developed. So, we can’t expect to see terms like “sexual orientation” or “gay” in the text.

There’s also the recent criminalization of sexual relations of any kind between men. So, references to “medico-legal” interest, “unnatural iniquity,” and being “false to human nature” are clearly coded imputations of male, same gender sexuality.[10]

According to literary critic Richard Ellman, after the publication of The Picture of Dorian Gray, “Victorian literature had a different look.”[11] More importantly, as Art is wont to do, Wilde’s novel altered the way Victorians saw and understood the world they lived in, particularly regarding sexuality and masculinity.

The backlash evident in outraged reviews like the one above – with their coded language and allusions to criminal prosecution – shows very clearly that many early British readers were aware of the ways this book refers to same gender sexuality. And, in doing so, it was challenging Victorian notions of masculine sexuality.[12]

As a result, Wilde’s work and life – the trials for “gross indecency” in particular – are widely credited as the impetus for same gender sexuality being seen as a distinct sexual orientation and social identity.[13]

Setting The Scene

With Flowers

Wilde’s use of floral imagery in the opening paragraphs of The Picture of Dorian Gray has been seen as linking Basil Hallward’s studio to Victorian London’s Artists’ colonies – which it absolutely does. [14] Given the popularity of floriography during this time, however, we can’t ignore Wilde’s choice of flowers and what these selections reveal.

Floriography is the language of flowers. And, it was a widely popular form of coded communication in the Victorian era. This cryptological system attaches specific and subtle meanings to individual varieties of flowers.

This form of code produces a hidden message for the intended recipient of the blooms in question, frequently revealing how the sender feels about the receiver. In this case, Wilde’s floriographic message is intended for the Victorian-era readers of Dorian Gray, an audience well-versed in the language of flowers and sure to understand its coded meaning.*[15]

Wilde uses flowers in the opening passage to set the emotional stage, to let the reader know love is literally in the air:

The studio was filled with the rich odour of roses, and when the light summer wind stirred amidst the trees of the garden, there came through the open door the heavy scent of the lilac, or the more delicate perfume of the pink-flowering thorn.[16]

As anyone who has ever watched a rom com knows, roses signify love (the type, of course, depends on the variety of rose). So, love is indeed literally in the air.

The scent of lilacs that comes wafting through the studio door, indicates youthful innocence and the first emotions of love. And, the delicate perfume of the Maiden Blush Rose, a very fragrant pink variety of rose common in Victorian gardens conveys the message “If you love me, you will find it out.”[17]

The stage is set. The Victorian reader knows that the conversation that follows will concern the first blush of romantic love, as well as the fact that these feelings remain undisclosed.

I turned half-way round and saw Dorian Gray for the first time. When our eyes met, I felt that I was growing pale. A curious sensation of terror came over me. I knew that I had come face to face with someone whose mere personality was so fascinating that, if I allowed it to do so, it would absorb my whole nature, my whole soul, my very art itself.[18]

Wilde’s floral choices are more than just purple prose, their symbolic meaning makes it clear to the Victorian reader that passages like this one – text that appears simply vague to the modern reader – are not so ambiguous after all. To Dorian Gray’s original audience, it was perfectly clear that the studio’s occupant, Basil Hallward, has an amorous attraction to a young man named Dorian Gray.

And the reason Basil refuses to exhibit the portrait of Dorian Gray is because he is “afraid [he] might have shown with it the secret of [his] soul” – and he doesn’t want to inadvertently “out” himself in modern parlance.[19] Elaborating on his first encounter with Dorian, Basil reveals to Lord Henry Wotton:

Something seemed to tell me that I was on the verge of a terrible crisis in my life. I had a strange feeling that Fate had in store for me exquisite joys and exquisite sorrows. I knew that if I spoke to Dorian I would become absolutely devoted to him, and that I ought not to speak to him.[20]

As Oscar Wilde indicated in the letter mentioned above, this is how he sees himself, as having genuine feelings for another man, but needing to remain closeted due to societal pressures – the vilification of same gender sexuality that ultimately ruined him.

The source for this essay is the uncensored version of The Picture of Dorian Gray. And as previously mentioned, Wilde edited – or more accurately, self-censored – the book after the backlash following its first appearance.

He deleted the lines “I knew that if I spoke to Dorian I would become absolutely devoted to him, and that I ought not to speak to him” from the above passage in the 1891 book version, the one most of us are familiar with. This deference to social pressure underscores Wilde’s concern for his own reputation.

Lilacs:

Symbol Of Dorian’s Innocence

As noted earlier, the lilac means innocence. And this symbolism evolves over the course of the first couple of chapters. The scent of lilacs refers to Basil’s feelings for Dorian, indicating the genuine and loving nature of his emotions.

And the flower signifies Dorian Gray’s character early in the text. Lilac blooms (rather than just their fragrance) are mentioned as Basil begins to tell the story of how he met Dorian. At this point, Dorian was innocent in the sense that he hadn’t realized his inclination toward same gender sexuality.

But, as a result of a conversation with Lord Henry Wotton – one laden with sexual innuendo and coded remarks about hidden impulses – Dorian comes to recognize what we would now call his sexual orientation:

Yes: there had been things in his boyhood that he had not understood. He understood them now. Life suddenly became fiery-coloured to him. It seemed to him that he had been walking in fire. Why had he not known?[21]

Like many transformative moments, Dorian finds this bewildering and uncomfortable – especially in a society as hostile to the idea of same gender sexuality as the Victorian era. So, he excuses himself from Basil’s studio to get some fresh air in the garden. And:

Lord Henry went out to the garden and found Dorian Gray burying his face in the great cool lilac-blossoms, feverishly drinking in their perfume as if it had been wine.[22]

Dorian realizes that his true sexual orientation is toward same gender sexuality. And yet, he remains innocent – now in the sense of not being vilified, and considered evil by society. This is who Oscar Wilde would like to be, a man who loves other men and is still accepted by the society he lives in.

Laburnum Signifies

Lord Henry’s Poisonous Nature

As indicated in the following passage, Lord Henry Wotton, an influential and cynical character, is associated with the laburnum tree:

From the corner of the divan of Persian saddle-bags on which he was lying, smoking, as was his custom, innumerable cigarettes, Lord Henry Wotton could just catch the gleam of the honey-sweet and honey-coloured blossoms of a laburnum, whose tremulous branches seemed hardly able to bear the burden of a beauty so flamelike as theirs…[23]

Laburnum is a poisonous plant that means “forsaken” in the language of floriography. The message being conveyed to recipients of laburnum is that the sender sees them as deserving to be abandoned by society.[24]

Consistent with the virulent aspect of laburnum, Lord Henry “poisons” Dorion by introducing him to notions like “every impulse that we strive to strangle broods in the mind,” and “the only way to get rid of a temptation is to yield to it.”[25] In doing so he, seemingly intentionally, destroys any possibility of a loving relationship between Basil and Dorian.

He strikes a nerve when he says to Dorian:

You, Mr. Gray, you yourself, with your rose-red youth and your rose-white boyhood, you have had passions that have made you afraid, thoughts that have filled you with terror, day-dreams and sleeping dreams whose mere memory might stain your cheek with shame…[26]

Lord Henry is intensely interested in Dorian. And his discourse clearly refers to same sex attraction, intending to test Dorian’s receptiveness to such remarks.

Dorian’s first response was to tell Lord Henry to “Stop!” to refrain from talking to him in this manner. But after further psychological prodding by Lord Henry, Dorian drops the spray of lilac he was holding during their conversation, indicating his loss of innocence… as he “listened, open-eyed and wondering.”[27]

It is significant that Lord Henry, linked to the poisonous laburnum tree, is introduced to the reader even before we meet Basil Hallward. For, this is how Wilde feels the world sees him, poisonous and predatory.

What Is Minority Stress?

And How Does It Affect

The Mental Health Of Gay Men?

Minority stress is psychosocial stress caused by chronic exposure to the social stresses that sexual minority individuals face due to their stigmatized status (relative to the cisgender heterosexual population that is). Minority stress differs from general stress – the kind all of us may experience – because it is born of stigma and prejudice.

What is known as proximal stressors are also part of the collective package that is minority stress. And, they emerge from a socialization process where sexual and gender minority individuals learn to reject themselves for being LGBTQIA. In Dorian Gray’s case, internalized homophobia.

Another such stressor occurs when sexual and gender minority individuals develop the expectation to be stigmatized, a result of their awareness of prevailing social stigma. Hiding your identity to protect yourself from such social stigma – being closeted in modern parlance – is also a proximal stressor.

Studies indicate these stressors have a significant association with a number of mental health concerns. Unfortunately, but understandably, men with high levels of minority stress are twice to three times more likely to suffer from psychological distress such as demoralization, guilt, – and all too often – suicide ideation and behavior.[28]

Dorian’s Internalized Homophobia

LGBTQIA individuals have internalized a hostile society’s negative attitudes toward sexual and gender minorities long before they recognize their own orientation and sexuality. And, logically, when they do realize their (in Dorian’s case) same-sex attraction, they begin to apply the term LGBTQIA to themselves.

As this self-labeling begins, however, LGBTQIA individuals also begin to apply the negative societal attitudes they’ve absorbed to themselves. And, that’s when the psychologically-injurious effects of a hostile society take effect.

Along with the recognition of same-sex attraction, a “deviant identity” starts to emerge, one that threatens the psychological well-being of the LGBTQIA individual in question.[29] This is the process we see play out when Dorian Gray looks at his portrait for the first time.

Dorian made no answer, but passed listlessly in front of his picture and turned towards it. When he saw it he drew back, and his cheeks flushed for a moment with pleasure. A look of joy came into his eyes, as if he had recognized himself for the first time.[30]

Dorian does indeed recognize himself for the first time, finally realizing his same-sex orientation. He also takes in “the sense of his own beauty” – in other words innocence – just as he begins to comprehend Lord Henry’s remarks about aging.[31]

Lord Henry points out that the grace of his figure would become “broken and deformed,” “the scarlet would pass away from his lips and the gold steal from his hair.”[32] This is, of course, how society would now see him as an LGBYQIA individual, “ignoble, hideous and uncouth.”[33]

As he thought of it, a sharp pang of pain struck through him like a knife and made each delicate fibre of his nature quiver. His eyes deepened into amethyst, and across them came a mist of tears. He felt as if a hand of ice had been laid upon his heart.[34]

Dorian Gray’s internalized homophobia has clearly emerged. And, his wish to remain young signifies a desire to continue being seen as he was before his revelation about the true nature of his sexual orientation… in a positive manner, as Lady Brandon described him to Basil – “charming.”[35]

The painting that gives rise to this wish represents the deviant entity that is psychological damage. Later in the text, Wilde asks whether the picture would “teach [Dorian] to loathe his own soul.”[36] Psychologically speaking, the answer is yes.

Dorian’s Denial

A Symptom Of Internalized Homophobia

One of the more common forms of internalized homophobia is to deny your true sexual orientation.[37] And, Dorian’s relationship with Sibyl Vane indicates that, at this point in the narrative, he is in denial.

Barely a month after Dorian came to recognize his same gender sexual orientation, he announces to Lord Henry that he’s in love with a young woman named Sybil Vane:

I love Sybil Vane. I wish to place her on a pedestal of gold, and to see the world worship the woman who is mine. What is marriage? An irrevocable vow. And it is an irrevocable vow that I want to take. Her trust makes me faithful, her belief makes me good. When I am with her, I regret all that you have taught me. I become different from what you have known me to be. I am changed, and the mere touch of Sybil Vane’s hand makes me forget you and all your wrong, fascinating, poisonous, delightful theories.[38]

This sounds more like a vindication of his denial than a testament of true love. Dorian wants the world to see the “woman who is mine.” In other words, he wants the world to see him conforming to the dominant heterosexual culture. And in doing so, annihilate the possibility of having same sex desires.

“Her trust makes me faithful, her belief makes me good” – in short, Sybil’s presence will keep Dorian in line with societal norms. When he’s with her, he regrets everything Lord Henry has taught him. The mere touch of her hand “makes [him] forget [Lord Henry] and all [his] wrong, fascinating, poisonous, delightful theories.” So in Dorian’s mind, he can’t actually be gay… but notice the words “fascinating,” and “delightful” woven into his refutation.

And let’s not forget what he found so attractive about Sybil’s acting:

Sybil was playing Rosalind. Of course the scenery was dreadful, and the Orlando absurd. But Sybil! You should have seen her! When she came on in her boy’s dress she was perfectly wonderful.[39]

Sybil’s role as Rosalind, in her “perfectly wonderful” “boy’s dress” blurs the gender lines for Dorian. And, she’s good at pretending to be someone she really isn’t – which is precisely what Dorian is trying to do.

When Sybil’s acting ability flounders and he is forced to see her for who she really is, his interest dies as well. So, he breaks off their engagement, in cruel and uncertain terms. And, the effects of Dorian’s denial-based psychological gymnastics manifest in the painting.

Basil’s Outwardly Hostile Form

Of Internalized Homophobia

The fateful night when Basil Hallward shows up on Dorian’s doorstep, before his departure on the midnight train for Paris, he embodies a form of internalized homophobia that occurs when LGBTQIA individuals negatively judge others sexual and gender minority individuals.[40]

Dorian ran into him on the street, and when he did, a “strange sense of fear, for which he could not account, came over him.”[41] After a few minutes of small talk, Basil makes it clear that he wants to address “the hideous things people are whispering about [Dorian].”[42]

Basil immediately begins to read Dorian the riot act, as the expression goes, launching into a lengthy diatribe:

Why is it, Dorian, that a man like the Duke of Berwick leaves the room of a club when you enter it? Why is it that so many gentlemen in London will neither go to your house nor invite you to theirs?…

Why is it that every young man that you take up seems to come to grief, to go to the bad at once? There was that wretched boy in the Guards who committed suicide. You were his great friend. There was Sir Henry Ashton, who had to leave England, with a tarnished name. You and he were inseparable. What about Adrian Singleton, and his dreadful end?...[43]

You get the picture. And that was just the beginning. Basil continues his harangue, actually taking it up a notch and getting downright parental:

I do want to preach to you. I want you to lead such a life as will make the world respect you. I want you to have a clean name and a fair record. I want you to get rid of the dreadful people you associate with. Don’t shrug your shoulders like that. Don’t be so indifferent…[44]

After getting a look at the portrait he painted of Dorian all those years ago, Basil really lets loose:

My God! if it is true… and this is what you have done with your life, why, you must be worse even than those who talk against you fancy you to be!…

Pray, Dorian, pray… What is it that one was taught to say in one’s boyhood? Lead us not into temptation. Forgive us our sins. Wash away our iniquities. Let us say it together.[45]

At that point, Dorian feels like a “hunted animal,” an apt description of how it must feel to be on the receiving end of an openly hostile society. So, Dorian picks up the knife that was lying on a chest a few feet away, one that was there because he’d used it a few days earlier to cut a piece of chord. And, in short, he stabs Basil to death with it.

Symbolically speaking, Basil’s murder is psychological and emotional self-defense. And once again, the psychological damage – this time the result of enduring an openly hostile society – appears in the painting.

Gossip And Scandal

A Source Of Minority Stress

Between cycles of denial, Dorian was a bit of a “wild child” as the expression goes. One who was beginning to create an unfavorable reputation for himself. And it was this gossip, and the need to avoid scandal, that Basil was confronting Dorian about on his way to Paris.

Scandals are ubiquitous social phenomena. They’re the public event par excellence, creating a singular dramatic intensity by mobilizing significant amounts of emotional energy, usually with momentous consequences.

They discredit and disgrace by undermining the social standing and reputation of those they effect. The most important thing to remember about a scandal, however, is that its power of contamination is derived from shame.[46] And this shame appears in the painting.

A careful reader notices that The Picture of Dorian Gray’s opening pages contain a comment about the sudden disappearance of Basil Hallward a number of years earlier.

Basil’s disappearance was evidently quite the scandal. The reference points out that it caused “such public excitement, and gave rise to so many strange conjectures” when it occurred.[47]

This phrase suggests that The Picture of Dorian Gray is a story being conveyed as gossip, one that keeps the scandal surrounding Basil Hallward’s disappearance alive after all these years.

There’s also the rumor that Dorian was seen “brawling with foreign sailors” in the “distant parts of Whitechapel.”[48] The scuttlebutt was that he “consorted with thieves and coiners and knew the mysteries of their trade.”[49] And, much ado was made about his absences from the city.

As a result of this gossip, Dorian was “blackballed at a West End Club of which his birth and social position fully entitled him to become a member.”[50] When a friend of Dorian’s brought him into the smoking-room of the Carlton, the Duke of Berwick and another gentleman stood up “in a marked manner,” and left the room.

Lord Henry makes the following remark in the 1891 version of The Picture of Dorian Gray, “the books that the world calls immoral are books that show the world its own shame.”[51] The shame Wilde seems to be exposing to the reader is Victorian society’s propensity to vilify men who love other men as evil, and ruining them with scandalous gossip.

The psychological damage associated with being the subject of gossip and scandal appears on Dorian’s portrait too.

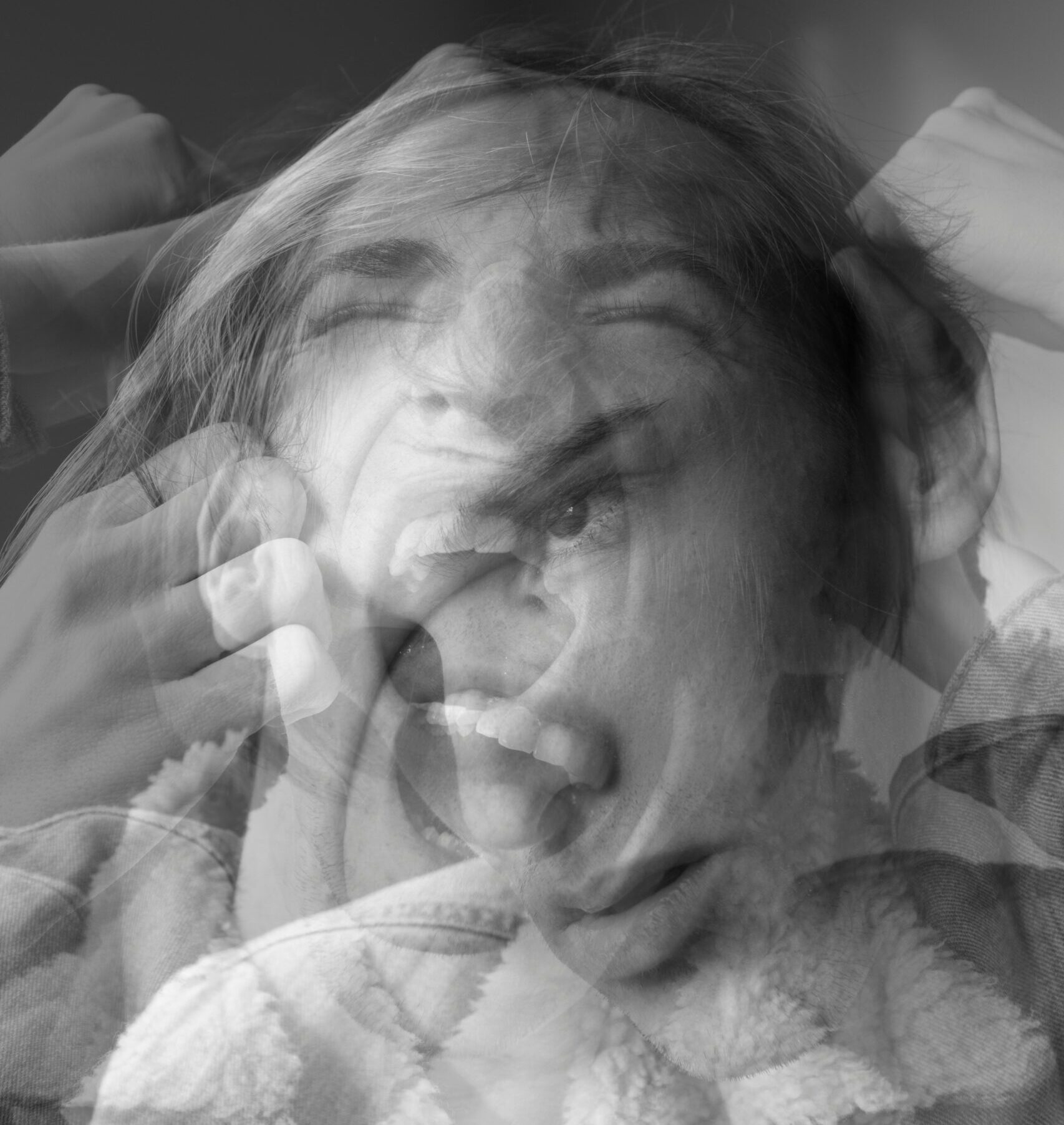

Psychological Maladies:

Demoralization And Guilt

Over time, Dorian has clearly come to accept that he is indeed attracted to other men. But, given the societal stigma associated with such sexuality, and potential social ruin should it become known, he must hide his true orientation.

Therefore, for many years, Dorian has been immersing himself in intellectual and philosophical endeavors as a “means of forgetfulness, modes by which he could escape, for a season, from the fear that seemed to him at times to be almost too great to be borne.”[52]

But repressing your true self is extremely psychologically taxing. So, as mentioned above, he has also periodically embarked on “mysterious and prolonged absences,” when he would engage in things like those Basil was berating him for. It was his habit, for example, to frequent places like “the little ill-famed tavern near the Docks” – in disguise and using a false name, of course.[53]

When he met Hetty Merton, Dorian was showing signs of demoralization and guilt, the psychological maladies that typically develop as a result of such minority stress.

Once again, Dorian relates the story of his relationship with a woman to Lord Henry. Only this time around, the plan isn’t to marry Hetty. It’s simply to set her up in a place he would visit every now and again. Nevertheless, like Lord Henry’s marriage, an arrangement with Hetty would go a long way toward keeping gossip about Dorian’s sexual orientation at bay.

She was quite beautiful, and wonderfully like Sybil Vane. I think it was that which first attracted me to her. You remember Sybil, don’t you? How long ago that seems! Well, Hetty was not one of our own class, of course. She was simply a girl in a village. But I really loved her. I am quite sure that I loved her.[54]

Dorian’s pronouncement of his love for Hetty is clearly more subdued than his enthusiastic attestation of love for Sybil Vane. The phrase “I am quite sure that I loved her” comes across as downcast and dispirited.

It sounds more like he’s trying to convince himself he had some sort of affection for her, feelings that would make a convenience relationship bearable, rather than a declaration of romantic love.

During their conversation regarding Hetty, Dorian talks with Lord Henry about how many “dreadful things” he has done in his life, things that he is “not going to do anymore.”[55] Dorian declares “I am going to alter. I think have altered.”[56]

And, to prove it (at least to himself) he reveals that his reason for ending the relationship with Hetty was because he “didn’t want to bring her shame.”[57] Whether that’s actually the case or Dorian is simply despondent, he’s clearly immersed in the demoralization and guilt that minority stress so frequently gives rise to.

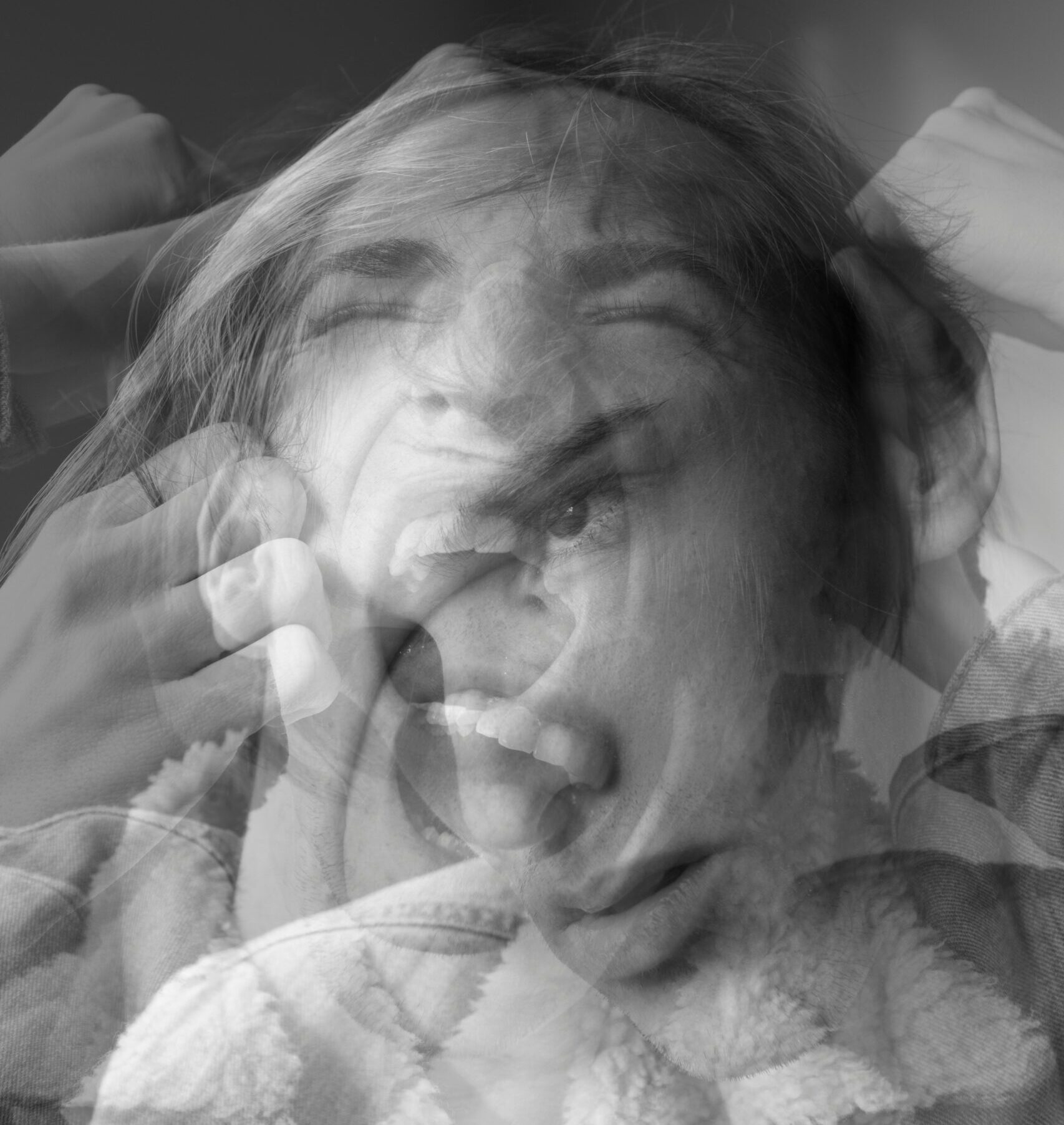

Self-Loathing:

Suicide Ideation & Behavior

As Dorian was walking home from Lord Henry’s following their conversation about Hetty, two young men passed him on the sidewalk, and he heard one of them whisper to the other “That is Dorian Gray.”[58] He used to be pleased when he was recognized or talked about, but not anymore.

Given the number of whispering campaigns about him making their way through the social community these days, to say nothing of the open hostility he’s experienced, “He was tired of hearing his own name.”[59]

When he made it home and was settling in for the night, Dorian began to wonder if it was really true that we can never change. And, he “felt a wild longing for the unstained purity of his boyhood.”[60] This sentiment sent Dorian sliding into self-loathing:

He knew that he had tarnished himself, filled his mind with corruption, and given horror to his fancy; that he had been an evil influence to others, and had experienced a terrible joy in being so; and that of the lives that had crossed his own it had been the fairest and the most full of promise that he had brought to shame. But was it all irretrievable? Was there no hope for him?[61]

Hetty Merton popped into his head again and the good he had done in her regard. And, Dorian began to wonder if the painting locked away upstairs had changed. Maybe if his life became pure, he would be able to erase all the signs of his “evil passion” from its face.[62]

So, he went to take a look. He locks the door behind him as usual, and uncovers the portrait. And when he did “a cry of pain and indignation broke from him.”[63] There had been no improvement. In fact, there was a new look of cunning in the eyes.

In the mouth he saw “the curved wrinkle of the hypocrite,” which wasn’t there before.[64]

And, the hypocrisy he saw was that of living a life in conflict with his true self. His portrait appeared more loathsome than ever.

It didn’t seem to matter how he went about trying to fit into a repressive, hostile, anti-LGBTQIA society as a sexual and gender minority. And, all the psychological damage he had endured due to minority stress remained visible in the painting.

The internalized homophobia that created this deviant entity was obviously there. The psychological gymnastics of denial was clearly evident. Feeling like a hunted animal in an openly hostile society was also there, conspicuously so.

So, Dorian looked around the room, and picked up the same knife that had stabbed Basil Hallward:

As it had killed the painter, so it would kill the painter’s work, and all that that meant. It would kill the past, and when that was dead, he would be free.[65]

The “painter’s work,” of course, means the deviant entity that emerges from internalized homophobia. In trying to put an end to it, and the psychological distress his portrait embodied, Dorian ended up killing himself.

He was found lying on the floor… dead – bearing all the scars once exhibited by his portrait.

In Conclusion

The lives of far too many LGBTQIA individuals end the same way Dorian Gray’s did. And, that’s after enduring years of psychological trauma, caused by the stigma that comes with trying to navigate living in a hostile, anti-LGBTQIA society.

If you’re an LGBTQIA individual, it’s psychologically important to see yourself represented. And if you aren’t a sexual and gender minority, seeing members of the LGBTQIA community in books and media is just as beneficial psychologically.

There’s a lot of Othering going on, divisive fear mongering about people who have different life experiences than our own. That’s what all this book banning is about.

But, when we read books about people who have different life experiences than ours, we realize there’s nothing to be afraid of. We see that we’re all just trying to make our way in the world, and that we have more in common than the fear mongers would have us believe.

It isn’t just right to try and understand those around us and see them us equals. It’s psychologically beneficial… because nobody wants to spend their lives living in a Twilight Zone where they’re constantly afraid. The Picture of Dorian Gray shows us how that ends up.

That’s my take on The Picture of Dorian Gray — what’s yours?

.

Use this discussion guide to inspire in-depth thinking,

and jump-start a conversation.

And, download Wilde’s norm-busting work here.

Share This Post, Choose a Platform!

Endnotes:

[1] Alan Turing was a mathematician credited with developing a modern computer that aided British espionage efforts during World War II. Turing also had sex with men and, as a result, was branded a security threat and convicted under a criminal code that outlawed sex between men. In addition, he was barred from continuing his government consultancy. He was also forced to receive hormonal treatments to reduce his libido. And, in 1954, he died in 1954 by poisoning himself with cyanide.

Hodges, A. Alan Turing the enigma. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014.

“Facts About Suicide Among LGBTQ+ Young People.” The Trevor Project. Jan 1, 2024. https://www.thetrevorproject.org/resources/article/facts-about-lgbtq-youth-suicide/

[2] Wilde, Oscar. Selected Letters of Oscar Wilde, ed. Rupert Hart-Davis. New York: Oxford University Press, 1979. Pg 116.

[3] Frankel, Nicholas. “General Introduction.” In Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 14.

[4] Banned and Challenged Mystery Books to Read Now. PBS.org https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/masterpiece/specialfeatures/banned-and-challenged-mystery-books-to-read-now/#

[5] Unsigned notice of The Picture of Dorian Gray, Scots Observer, July 5, 1890; rpt. In Oscar Wilde: The Critical Heritage ed. Beckson, p 75.

Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine. Vol 46, July 1890.

[6] Frankel, Nicholas. “Textual Introduction.” In Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011.. Pg 39.

[7] The National Vigilance Association was a private British organization that focused on “for the enforcement and improvement of the laws for the repression of criminal vice and public immorality.” Records of the National Vigilance Association. https://archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/search/archives/a97a5bcd-eb99-31df-b564-8e75a4c33fb7

[8] Adut, Ari. “A Theory of Scandal: Victorians, Homosexuality, and the Fall of Oscar Wilde.” American Journal of Sociology. Vol. 111 No. 1. July 2005. Pg 224.

[9] Frankel, Nicholas. “General Introduction.” In Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 7.

[10] Frankel, Nicholas. “General Introduction.” In Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 7.

[11] Ellman, Richard. “A Late Victorian Love Affair.” The New York Review of Books. August 4, 1977.

Oscar Wilde: A Collection of Critical Essays. Edited by Richard Ellman. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 1969. Pg 314.

[12] Frankel, Nicholas. “General Introduction.” In Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 7.

[13] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 9.0) May 1895. Trial of OSCAR FINGAL O’FFLAHARTIE WILLS WILDE (40), ALFRED WATERHOUSE SOMERSET TAYLOR (33) (t18950520-425). Available at: https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/record/t18950520-425

Appleman, Laura I. “Oscar Wilde’s Long Tail: Framing Sexual Identity in the Law.” Maryland Law Review. Volume 70, Issue 4. Pp 985-1043. July, 2011.

[14] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 67.

[15] * After 1892, the green carnation Oscar Wilde famously sported was seen as suggesting that the wearer was a man who loved other men. It was in that year Wilde had a handful of friends wear them on their lapels to the opening night of his comedy Lady Windermere’s Fan. The symbolism is said to be based on the idea that a green carnation embodies the “unnatural.” And, in those days the first thing most people would think of when they heard that word would be “unnatural love,” i.e. same gender sex.

“Four Flowering Plants That Have Been Decidedly Queered.” Jstor Daily. https://daily.jstor.org/four-flowering-plants-decidedly-queered/

“Why the Green Carnation?” Oscar Wilde Tours. https://www.oscarwildetours.com/our-symbol-the-green-carnation/

Museum Selection.co.uk https://www.museumselection.co.uk/victorian-language-of-flowers/

Pearson, Rachel. “The Petals of Dorian Gray.” Boston University. December 4, 2011.

[16] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 67.

[17] Mrs. L Burke. The Illustrated Language of Flowers. London: George Routledge and Sons, 1867. Pg 36 and 52.

[18] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 79.

[19] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 78.

[20] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 79.

[21] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 96.

[22] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 97.

[23] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 67.

[24] Mrs. L Burke. The Illustrated Language of Flowers. London: George Routledge and Sons, 1867. Pg 35.

Pearson, Rachel. “The Petals of Dorian Gray.” Boston University. December 4, 2011.

[25] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 94, 96.

[26] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 96.

[27] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 100.

[28] Meyer, Ilan H. “Minority stress and mental health in gay men.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior. Washington Vol. 36, Issue 1. March, 1995.

[29] Meyer, Ilan H. “Minority stress and mental health in gay men.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior. Washington Vol. 36, Issue 1. March, 1995.

[30] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 101.

[31] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 102.

[32] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 102.

[33] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 102.

[34] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 102.

[35] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 80.

[36] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 150.

[37] Richard C. Friedman M.D. and Jennifer Downey M.D. “Internalized Homophobia and the Negative Therapeutic Reaction.” Guilford Journals, 2022. https://guilfordjournals.com/doi/pdf/10.1521/pdps.2022.50.1.88

“10 Signs of Internalized Homophobia and Gaslighting.” May 21, 2020. Psychology Today.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/communication-success/202005/10-signs-internalized-homophobia-and-gaslighting

[38] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 136.

[39] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 134.

[40] “10 Signs of Internalized Homophobia and Gaslighting.” May 21, 2020. Psychology Today.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/communication-success/202005/10-signs-internalized-homophobia-and-gaslighting

[41] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 210.

[42] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 215.

[43] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 215.

[44] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 216.

[45] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 223.

[46] Adut, Ari. “A Theory of Scandal: Victorians, Homosexuality, and the Fall of Oscar Wilde.” American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 111, No 1. July, 2005. Pg 217-221.

[47] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 67.

[48] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011.Pg 202.

[49] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011.Pg 202.

[50] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011.Pg 202.

[51] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray. London: Simpkin, Marshall Hamilton, Kent and Co. LTD, 1891. Pp 241-242.

[52] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 201.

[53] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. P 188.

[54] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. P 242.

[55] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 241.

[56] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 241.

[57] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 241.

[58] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 248.

[59] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 248.

[60] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 248.

[61] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 248.

[62] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 249.

[63] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 249.

[64] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 249.

[65] Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of The Harvard University Press, 2011. Pg 252.

Images:

Dorian Gray in Chains: Charles Ricketts-Public Domain https://archive.org/stream/pictureofdoriang00wildrich#page/n7/mode/2up

Controversial from the start: Unknown author – From part one of The Elmer Holmes Bobst Library’s online exhibition: Reading Wilde, “Querying Spaces: An Exhibition Commemorating the 100th Anniversary of the Trials of Oscar Wilde” Public Domain

Terms like “sexual orientation” didn’t exist: Photo by stephen packwood on Unsplash

Setting the scene with flowers: Photo by Cody Chan on Unsplash

Lilacs, the symbol of Dorian’s innocence: Photo by Dmitry Tulupov on Unsplash

Laburnum signifies Lord Henry’s nature: MySeeds.co

Minority Stress: Photo by George Pagan III on Unsplash

Dorian’s internalized homophobia: Photo by amir maleky on Unsplash

Dorian’s Denial: Photo by Saif71.com on Unsplash

Basil’s internalized homophobia: Photo by Callum Skelton on Unsplash

Gossip and Scandal – A source of Minority Stress: Photo by Joseph Corl on Unsplash

Psychological maladies – demoralization and guilt: Photo by Melanie Wasser on Unsplash

Self-loathing – suicide ideation & behavior: Photo by Louis Galvez on Unsplash

Pride Flag: Image by rawpixel.com on Freepik.

![]() F

F

L

L