The Crucible: A serving of literary layer cake.

.

.

he Crucible is a notable example of how literature is like a layer cake. Arthur Miller’s account of why he came to write this play also touches upon how it is written, outlining the multi-layered nature of the work. Miller’s delineation of his play’s layers demonstrates why it’s important to get every bite of literary confections like The Crucible.

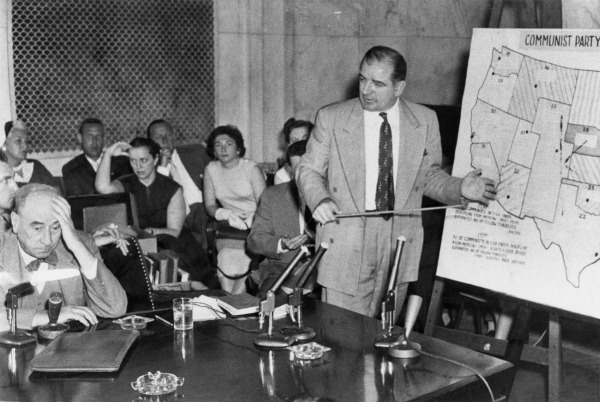

When The Crucible first opened on the Broadway stage in 1953, America was in the midst of what’s known as the Red Scare, a period of public hysteria about a perceived internal Communist threat.[1] The American psyche was fixated on the Congressional investigations being conducted by the House Un-American Activities Committee.[2]

The Environment of the Day

The House Un-American Activities Committee targeted the Hollywood film industry, ushering in an era of blacklisting media workers. In order to promote their patriotic credentials, Hollywood studios implemented a blacklist. Scores of writers and media workers were banned from employment because of their perceived political leanings. And all it took was a rumored association with so-called “subversives” to ruin a career.[3]

In fact, Miller himself was called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee (in 1956). And he was cited for contempt of Congress for refusing to point a proverbial finger in any other writers’ direction.[4]

Miller was motivated to write The Crucible in large part by what he describes as the “paralysis that had set in” among those who were unsettled by the committee’s violations of civil rights, but fearful of being identified as a covert Communists themselves if they protested too strongly.[5]

“In one sense,” Miller has stated, “The Crucible was an attempt to make life real again, palpable and structured.”[6] His hope was that the play “might illuminate the tragic absurdities” of what was going on in America during this period.[7]

Reference to American History

The Crucible, as Miller characterizes it:

.

straddles two different worlds to make them one, but it is but it is not history in the usual sense of the word, but a moral, political and psychological construct that floats on the fluid emotions of both eras.[8]

He further notes that writing a play about the Salem witch trials probably wouldn’t have occurred to him if he hadn’t noticed “some astonishing correspondences with the calamity” of the period.[9]

While both historical moments involved the menace of concealed plots, the most startling thing for Miller were the similarities in their investigative routines, and “rituals of defense.”[10] Prosecutorial practices of the Salem witch trials were remarkably similar to those employed by the congressional committees.[11]

They were 300 years apart, yet both prosecutions charged membership of a clandestine, disloyal group. And, even if the accused confessed, their honesty could only be proven by naming others who were in league with them.[12]

Miller also noticed corresponding behaviors between members of the two communities. For example, avoiding old friends so as not to be seen associating with them, and zealous confirmations of loyalty. Not to mention a despairing pity for the accused mixed with an underlying sentiment that they “must have done something.”[13]

With this realization, Miller explains:

.

My basic need was to respond to a phenomenon which, with only small exaggeration, one could say paralyzed a whole generation and in a short time dried up the habits of trust and toleration in public discourse.[14]

The Personal Level

Miller was only certain a play about the Salem witch trials was possible, however, when a particular entry in the documents he was researching “jogged” the thousands of pieces of information he had found into place.[15]

It became apparent to him that Abigail Williams was fired from domestic service in the Proctor household because Elizabeth’s husband John had “bedded” the young woman. He saw the bad blood between the two women as being what prompted Abigail to accuse Elizabeth Proctor of witchcraft.

“All this I understood,” Miller points out, “I had not approached the witchcraft out of nowhere, or from purely social and political considerations.”[16]

His own marriage of twelve years was teetering, and he was painfully aware that the blame lay with him. He had “at last found something of [him]self in it.”[17]

So, Miller began to build the play around the character of John Proctor. That Proctor might overturn his personal guilt and emerge as the most forthright voice against the lunacy that had a grip on the community was a reassurance to Miller. For him, it demonstrated that a “clear moral outcry could still spring” from a tarnished soul like his own.[18]

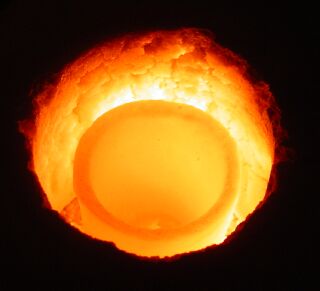

Symbolism of the Title

Miller sought a title that would literally indicate the burning away of impurities, “which,” as he explicitly states, “is what the play is doing.”[19] And the term crucible… well, it crystalizes that concept in a single word.

As Miller states, he couldn’t have written The Crucible simply to write a play about blacklisting – or about Salem’s witch trials for that matter. His play centers on “the guilt of John Proctor and the working out of that guilt,” exemplifying “the guilt of man in general.”[20] And there we have the fourth layer in our literary cake… universal themes.

Ongoing Relevance

Though many people still consider The Crucible to be a tract-like against McCarthyism, it’s more than a political metaphor. It’s also more than a simple morality tale. As Miller maintains:

.

On its most universal level, The Crucible is about community hysteria, fear of the unknown, the psychology of betrayal, the cast of mind that insists on absolute truth and resorts to fear and violence to assert it, and not least about the fortitude it takes to protect the innocent and resist unjust authority.”[21]

He draws a comparison between turning to Salem and looking in a petri dish. Three centuries before the cold-war, as Miller points out, Salem village displayed what he describes as a human “fatality forever awaiting the right conditions for its always unique, forever unprecedented outbreak of trust, alarm, suspicion.”[22]

And, he calls attention to the fact that this “fatality” isn’t about “just a crazy situation in a far-off place.”[23] Such events could (and often do) occur in a corporate boardroom, for example, or anywhere else unchecked power is prodigious. So, we can add ongoing relevance to the list of layers in our literary cake.

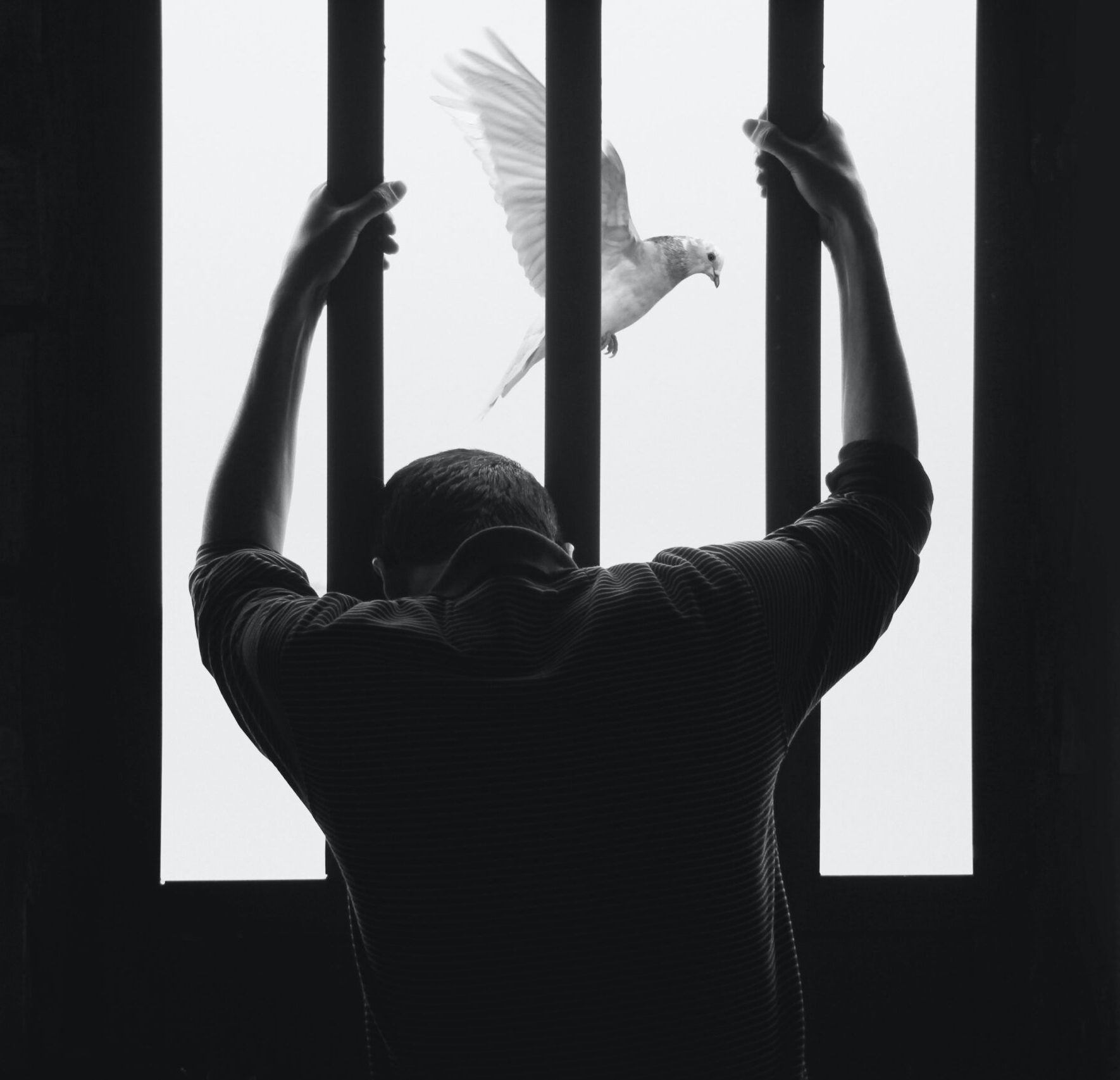

Beyond Themes of Paranoia

It’s important to remember that, as Miller makes abundantly clear, literary works like The Crucible function on multiple levels. As such, they aren’t intended to be read on a single level, whether that’s for plot and simple enjoyment, or the exploration of universal themes at the expense of historical and societal context.

Either of these common approaches flattens literary works, minimizing the diverse perspectives of unique identities, as well as the histories of various communities. Not to mention the fact that flattening a work hinders engaging it through the filter of current pressing civic issues.[24]

Where we arrive at what the reader “bring[s] to the party,” as Toni Morrison puts it.[25] This perspective also contributes to the layer count of our literary confection (which at this point is tall enough to resemble something out of Dr. Seuss.)

For example, educators have recently been teaching The Crucible with a view toward how mass hysteria, patriarchy, sexism, and scapegoating continue to operate today.

Some teachers use Miller’s play to initiate conversations about prison and bail reform. Still others employ The Crucible as a way to examine systems of privilege and power that marginalize people of color and other marginalized populations. [26]

When we examine all the layers within works like The Crucible, we begin to comprehend the real power of literature – to build understanding about the world we live in, to provoke questioning power structures that produce inequality, to foster empathy for those whose life circumstances are different than our own. And as a result, perhaps make our piece of the world a little better for everyone.[27] Which is why it’s so important to get every bite of these literary confections.

#the art of reading #banned books #witch trials #published 1950s #english literature #Benefits of the Humanities

Endnotes:

[1] Navaskh, Victor. “The Demons of Salem, With Us Still.” Sept. 8, 1996. The New York Times.

https://www.nytimes.com/1996/09/08/movies/the-demons-of-salem-with-us-still.html

“Red Scare.” April 21, 2023. The History Channel https://www.history.com/topics/cold-war/red-scare

“McCarthyism and the Red Scare.” University of Virginia Miller Center. https://millercenter.org/the-presidency/educational-resources/age-of-eisenhower/mcarthyism-red-scare

[2] Miller, Arthur. “Why I Wrote ‘The Crucible.’” Oct. 13, 1996. The New Yorker.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1996/10/21/why-i-wrote-the-crucible

[3] Perlman, Allison. “Hollywood blacklist.”Sept. 22, 2023. Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Hollywood-blacklist

“A look back at the Hollywood blacklist.” July 8, 2018. BrandeisNOW. https://www.brandeis.edu/now/2018/june/blacklist-qa-tom-doherty.html

[4] “Excerpts from Arthur Miller’s testimony before the House Un-American Activities Committee.” American Masters. April 2020. PBS. https://www.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/excerpts-from-arthur-millers-testimony-before-the-house-un-american-activities-committee/14006/

[5] Miller, Arthur. “Why I Wrote ‘The Crucible.’” Oct. 13, 1996. The New Yorker.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1996/10/21/why-i-wrote-the-crucible

[6] Miller, Arthur. “Are You Now Or Were You Ever?” The Guardian/The Observer (online), June 17, 2002. https://www.writing.upenn.edu/~afilreis/50s/miller-mccarthyism.html

[7] Miller, Arthur. “Are You Now Or Were You Ever?” The Guardian/The Observer (online), June 17, 2002. https://www.writing.upenn.edu/~afilreis/50s/miller-mccarthyism.html

[8] Miller, Arthur. “Are You Now Or Were You Ever?” The Guardian/The Observer (online), June 17, 2002. https://www.writing.upenn.edu/~afilreis/50s/miller-mccarthyism.html

[9] Miller, Arthur. “Are You Now Or Were You Ever?” The Guardian/The Observer (online), June 17, 2002. https://www.writing.upenn.edu/~afilreis/50s/miller-mccarthyism.html

[10] Miller, Arthur. “Are You Now Or Were You Ever?” The Guardian/The Observer (online), June 17, 2002. https://www.writing.upenn.edu/~afilreis/50s/miller-mccarthyism.html

[11] Miller, Arthur. “Why I Wrote ‘The Crucible.’” Oct. 13, 1996. The New Yorker.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1996/10/21/why-i-wrote-the-crucible

[12] Miller, Arthur. “Are You Now Or Were You Ever?” The Guardian/The Observer (online), June 17, 2002. https://www.writing.upenn.edu/~afilreis/50s/miller-mccarthyism.html

[13] Miller, Arthur. “Why I Wrote ‘The Crucible.’” Oct. 13, 1996. The New Yorker.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1996/10/21/why-i-wrote-the-crucible

[14] Miller, Arthur. “Are You Now Or Were You Ever?” The Guardian/The Observer (online), June 17, 2002. https://www.writing.upenn.edu/~afilreis/50s/miller-mccarthyism.html

[15] Miller, Arthur. “Why I Wrote ‘The Crucible.’” Oct. 13, 1996. The New Yorker.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1996/10/21/why-i-wrote-the-crucible

[16] Miller, Arthur. “Why I Wrote ‘The Crucible.’” Oct. 13, 1996. The New Yorker.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1996/10/21/why-i-wrote-the-crucible

[17] Miller, Arthur. “Why I Wrote ‘The Crucible.’” Oct. 13, 1996. The New Yorker.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1996/10/21/why-i-wrote-the-crucible

[18] Miller, Arthur. “Why I Wrote ‘The Crucible.’” Oct. 13, 1996. The New Yorker.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1996/10/21/why-i-wrote-the-crucible

[19] Mel Gussow and Arthur Miller. Conversations with Miller. New York: Applause Theatre & Cinema Books, 2002. Pg 185.

[20] Mel Gussow and Arthur Miller. Conversations with Miller. New York: Applause Theatre & Cinema Books, 2002. Pg 7.

[21] Navaskh, Victor. “The Demons of Salem, With Us Still.” Sept. 8, 1996. The New York Times.

https://www.nytimes.com/1996/09/08/movies/the-demons-of-salem-with-us-still.html

[22] Miller, Arthur. “Are You Now Or Were You Ever?” The Guardian/The Observer (online), June 17, 2002. https://www.writing.upenn.edu/~afilreis/50s/miller-mccarthyism.html

[23] Mel Gussow and Arthur Miller. Conversations with Miller. New York: Applause Theatre & Cinema Books, 2002.Pg 37.

[24] Mirra, Nicole. Reading, Writing, & Raising Voices: The Centrality of Literacy to Civic Education. 2022. NCTE: National Council of Teachers of English. Pg 5.

[25] Morrison, Toni. “The Reader as Artist.” O, the Oprah Magazine. Vol. 7, Issue 7. (July 2006), 174.

[26] Torres, Julia E. “Chat: Disrupting The Crucible.” June 12k 2018. DisruptTexts

https://disrupttexts.org/2018/06/12/disrupting-the-crucible/

[27] Ebarvia, Tricia. Disrupting Texts as a Restorative Practice.

https://triciaebarvia.org/2018/07/11/disrupting-texts-as-a-restorative-practice/#:~:text=%23DisruptTexts%20is%20a%20type%20of,choices%20we%20make%20as%20educators

Images:

First Edition Cover with “banned” lock.

The Environment of the Day: Senate Hearings http://www.senate.gov

Reference to American History: Cauldron-Photo by Matt Benson on Unsplash

The Personal Level: Broken pocket watch-Photo by Gaspar Uhas on Unsplash

Symbolism of the Title: A crucible https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crucible

Ongoing Relevance: Fanned Book-Photo by Anastasia Zhenina on Unsplash

Beyond Themes of Paranoia: Silhouette and bird-Photo by Hasan Almasi on Unsplash