We May Read for Enjoyment, but Literature Isn’t Written Just to Entertain Us.

P

P

eople have been telling stories since the dawn of time. But, storytelling has never been just about entertainment. Why are books written, then, if not for readers’ gratification?

As Ursula K. Le Guin points out, “There have been great societies that did not use the wheel, but there have been no societies that did not tell stories.”[1] That said, as much as some of us like to just kick back and ride a good narrative, storytelling has never been just about entertainment.

Narrative is so important because stories have always been the best way to pass on essential knowledge. It’s important to know the best place to look for grubs, for example, or the rules and expectations of the clan. Putting this information in an entertaining package not only helped it take root in young minds, a message embedded in an enjoyable story was more likely to be passed on.[2] And narrative continues to serve such a purpose.

The Celtic tale about a supernatural woman winning the footrace she was forced to run against the king’s chariot despite being in the throes of birth pangs, is a fantastic story to be sure.[3] But the underlying message in The Curse of Macha is that we should treat our mothers well. It isn’t called the “Curse” of Macha for nothing. Yarns about the child-snatching arctic sea monster Qallupilluk are exciting on their face, but the lesson is clear. “Inuit children, ‘it is never safe to play on the beach alone!’”[4] And the warning imbedded in the fairy tale thriller Little Red Riding Hood is quite simply, “don’t talk to strangers.”[5]

_________

Legends and Epic Poetry

Shape History and Cultural Beliefs.

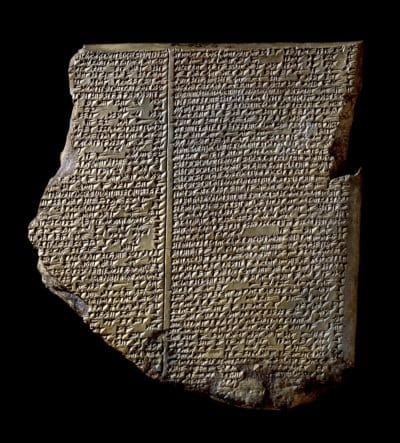

Take Gilgamesh for instance, said to be the oldest written story in the world.[6] The epic’s hero was a historical king of the Mesopotamian city Uruk, and versions of his legendary deeds had been handed down in oral fashion for hundreds of years. Gilgamesh’s exploits involve the face-changing monster Humbaba, a pantheon of gods and goddesses, not to mention the wild man Enkidu. Though they are indeed gripping tales of adventure, they were “printed” during the reign of King Shulgi (of the Third Dynasty of Ur) for a political purpose. King Shulgi claimed the gods and ancient Kings of Uruk as ancestors in order to strengthen the legitimacy of his own kingship.[7] Literally setting the epic in stone, or in this case clay tablets, gives King Shulgi’s claim an authority impervious to challenge. And given the permanent nature of the written word, he gets to control what is now an incontrovertible narrative.

When it comes to Virgil’s Aeneid who doesn’t love a good battle scene, especially one fueled by a vindictive goddess? But once again, there’s more to it than that. There is a longstanding view that Virgil was commissioned to write his epic poem by Emperor Augustus, in an effort to unite the Roman people after a long period of civil conflict. The Aeneid not only depicts the founding of Roman society, it hearkens back to a period of strength and glory in Rome’s past. Virgil uses the long-running conflict between Rome and Carthage to unify the Roman people by reminding them of a time when their greatest threat was from a foreign power.[8]

Merlin, and the references to dragons in Arthurian legend are great fun. But yet again, the reason for their existence is not entertainment. During the period following the Norman conquest of England, Celtic literature exploded. And much of it revolved around triumphs of Celtic Britons against their new masters, clearly sending a political message to the Normans. All such stories need a hero for the troops to rally around, which is where Arthur comes in. But the Normans were there to stay and ultimately, Arthurian legend served to introduce them to the culture and past of the Celts.[9]

_________

Literature is a Fundamental

Source of New Insights.

Literature, and a liberal arts education generally, is a fundamental source of cultivating new insights.[10] L. Frank Baum may have claimed that The Wonderful Wizard of Oz is simply a “wonder tale” written to bring pleasure to children of his era, but the fact that he characterizes his work as a “modernized fairy tale” confirms its function as commentary. Baum reveals one newly discovered insight by stating that the “fearsome morals” in the Grimm and Anderson tales are no longer necessary because “modern education includes morality.”[11]

Published in 1951, the insights expressed in J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye are in response to a newly nuclear world, post-World War II uniformity, and the numbing malaise produced by materialism. Catcher’s teenaged protagonist, Holden Caulfield, is the quintessential anti-hero. He considers just about everyone to be “phony,” as mindlessly falling in line with artificial conventions, and amiability is simply camouflage for self-interest. In a generation defined by conformity, Caulfield has been described as “an icon of restlessness, discontent, rebellion, opposition to the status quo.”[12] Holden Caulfield was a lightning rod for such sensibility, opening the door to the anti-establishment culture that defined the following decade (1960s).[13]

But what about The Zombie Survival Guide and its companion World War Z? Surely those are intended as entertainment. Nope. Needless to say, all writers want their books to be well-received, and Max Brooks is no different. But it is important to note that Brooks had the HIV epidemic in mind when he wrote those. Not to mention that the CDC was inspired to form a zombie task force, and to establish a Zombie Preparedness page on their website. The campaign is tongue-in-cheek of course, but the CDC put Brooks’ insights to use, in order to educate people about very real hazard preparedness.[14] More broadly, the first of these books is about responding to tragedy when it inevitably strikes, whether that tragedy takes the shape of a tornado, a flood, or the death of your mother, things “that come into your life without prejudice, and destroy it.”[15] The follow-up work, World War Z, is essentially how not to deal with such “zombies.”

_________

Books Allow us to See the World

Through Someone Else’s Eyes.

Perhaps the most important function literature serves is to enable us to see the world through someone else’s eyes. This viewpoint not only broadens our horizons, it helps us realize as Neil Gaiman phrases it “that behind every pair of eyes, there’s somebody like us.”[16] Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man specifically deals with this issue, of not being seen as a unique individual, but merely as a stereotype and therefore not fully human. Books like Ellison’s, that is works that facilitate a shift in perspective by shedding light on uncomfortable situations, may not be “fun,” but as you know by now, literature isn’t written just to entertain us.

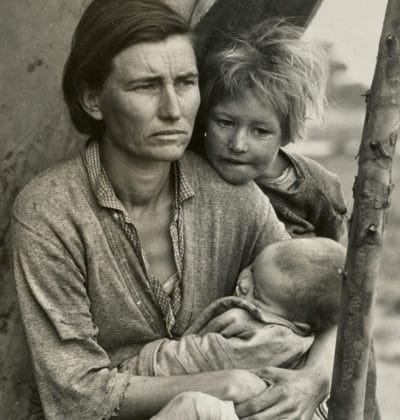

Concisely put, literature cultivates empathy. According to John Steinbeck, a base theme runs through “every bit of honest writing in the world,” and that theme is we should “try to understand men (and by that he means people).”[17] Elaborating on his point Steinbeck further stated, “if you understand each other you will be kind to each other.”[18] In keeping with his observation, the concept of understanding forms the foundation of Steinbeck’s novella Of Mice and Men. Bearing literature’s function of cultivating empathy in mind offers significant insight into other books like this one as well, those with a less than joyful plotline. Franz Kafka sums it up nicely, “If the book we’re reading doesn’t wake us up with a blow on the head, what are we reading it for?… A book must be the axe for the frozen sea inside us.”[19]

The understanding and kindness Steinbeck was referring to goes beyond the “be nice” variety we all learned about in kindergarten. As H. G. Wells observed, the success of civilization itself “amounts ultimately to a success of sympathy and understanding.”[20] Fittingly, Wells indicated that if it had been up to him, every candidate applying for the post of Workhouse Master would be required to pass an exam on Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist.[21] For Dickens was a master at revealing the humanity in characters typically seen as unsympathetic during the Victorian era. And in doing so, he exposed how inhumane the social institutions of his day were.

_________

Novels are a Powerful Platform

for Examining Societal Ills.

As Dickens’ work shows us, literature provides a powerful platform for examining societal ills. Novelists of every generation have put unjust, and inappropriate conduct on display. It is critical to remember, however, that depicting such behavior does not mean endorsing it. Sadly, the vast majority of “banned books” are deleted from school curriculums or removed from libraries, because those who challenge them fail to understand this very important point. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby is a perfect example of such unfortunate misinterpretation. Readings of this novel are all too often limited to plot, as a period piece set in the decadent “Roaring Twenties,” glorifying alcohol, adultery, and wealth obtained at any moral cost. Fitzgerald, of course, belonged to the World War I-era “Lost Generation.” In a clear Gatsby reference, Beat author John Clellon Holmes described the Lost Generation as “discovered in a roadster, laughing hysterically because nothing meant anything anymore.”[22] Fitzgerald is not condoning the self-destructive practices he depicts. Rather, he shines a light on this conduct as commentary on how devastating The Great War was, in the hope of waking people up to the fact that those lost on the battlefield were not the only casualties.[23]

Authors and their works continue to present, analyze, and illuminate social maladies through and through. Words may appear innocent and powerless when we see them in the dictionary, but as Nathaniel Hawthorne observes, they become incredibly potent “in the hands of one who knows how to combine them.”[24] Some social wounds are so cruel, and so deeply ingrained that, as Toni Morrison points out, unlike reparations, vengeance, or even the justice victims of societal ills seek, it is only writers who can turn such trauma and sorrow into meaning. Only writers can sharpen our moral imagination. Once again, and more emphatically than ever, literature is not written simply for a reader’s gratification. To quote Morrison precisely, “a writer’s life and work are not a gift to mankind; they are its necessity.”[25]

__

Be sure to check out these companion articles:

Novels are Like a Layer Cake,

Be Sure to Get Every Bite.

If You’re Not Engaging a Book’s Symbolic Language,

You Aren’t Really Reading It.

Literary Devices:

Literary Devices: The Author’s Toolbox

#literary criticism #The Art of Reading #liberal arts #critical thinking

Share This Post, Choose a Platform!

Endnotes:

[1] Le Guin, Ursula K. The Language of the Night: Essays on Fantasy and Science Fiction. (New York: Harper Collins, 1992), 22.

[2]Gaiman, Neil. “How Stories Last.” The Long Now Foundation. Video Seminar. (June 9, 2015).

[3] Gantz, Jeffrey. Early Irish Myths and Sagas. (New York: Penguin Books, 1981), 128-129.

[4] Qallupilluit. http://www.inuitmyths.com/story_qua.htm ; Doucleff, Michaeleen and Jane Greenhalgh. “How Inuit Parents Teach Kids To Control Their Anger.” NPR.org.

[5] Perrault, Charles. Tales of Passed Times. (London: J. M. Dent & Co, 1900), 23.

[6] Mitchell, Stephen. Gilgamesh: A new English version. (London: Profile Books Ltd., 2005), 8.

[7] Kovacs, Maureen Gallery. The Epic of Gilgamesh. (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1989), xxii-xxiii.

[8] “Making Rome great again: fake views in the ancient world.” University of Cambridge, Research.

[9] The British History of Geoffrey of Monmouth. Translated by A. Thompson, Esq. (1842 edition); Wood, Michael. “King Arthur, ‘Once and Future King.’” BBC History.

[10] Taylor, Charles. A Secular Age. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007), 732.

[11] Baum, L. Frank. The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. (New York: Harper Collins, 1987), 1.

[12] Shields, David and Shane Salerno. Salinger. (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2013), 260.

[13] Castronovo, David “Holden Caulfield’s Legacy.” New England Review. Vol. 22, No 2 (Sprint, 2001), 180; Shields, David and Shane Salerno. Salinger. (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2013), 260.

[14] Brodesser-Akner, Taffy. “I can’t think of anything less funny than dying in a zombie attack.” The New York Times. June 23, 2013; https://www.cdc.gov/cpr/zombie/index.htm

[15] Brodesser-Akner.

[16] Gaiman, Neil. “How Stories Last.” The Long Now Foundation. Video Seminar. (June 9, 2015).

[17] Steinbeck, John. Journal entry quoted in Steinbeck Center director Susan Shillinglaw’s introduction to the 1993 Penguin Classics edition of Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Kafka, Franz. Letters to Friends, Family and Editors. Translated by Richard and Clara Winston. (New York: Schocken Books, 2016), 16.

[20] Wells, H. G. “The Contemporary Novel.” The Atlantic Monthly. (January, 1912), 1.

[21] Wells.

[22] Holmes, John Clellon. “This is the Beat Generation.” The New York Times. Nov. 16, 1952.

[23] Licari, T. S. “’The Great Gatsby’ and the Suppression of War Experience.” The F. Scott Fitzgerald Review. (Vol. 17, 2019), 207-208.

[24] Nathaniel Hawthorne. Quoted by William Safire. “On language; Gifts of Gab for ’99.” New York Times Magazine. Dec. 13, 1998.

[25] Morrison, Toni. “Peril.” Burn this Book: notes on literature and engagement. Ed. Toni Morrison. (New York: Harper, 2009), 4.

Images:

[1] Legends and Epic Poetry. The Gilgamesh Flood Tablet is a Mesopotamian clay artifact created in 700 BCE. It lives at the The British Museum in London. The image is in the public domain, and tagged epic poem, cuneiform and artifact. Source: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/W_K-3375

[2] Literature is a Fundamental Source of New Insights. Photo by Kari Shea on Unsplash. https://unsplash.com/photos/QfAX7_xjxm4?utm_source=unsplash&utm_medium=referral&utm_content=creditShareLink

[3] See the World Through Someone Else’s Eyes. Photo by jesse orrico on Unsplash.

https://unsplash.com/photos/OqQyk8vN30k?utm_source=unsplash&utm_medium=referral&utm_content=creditShareLink

[4] Platform for Examining Societal Ills. Photo by The New York Public Library on Unsplash. https://unsplash.com/photos/fMFqbGVP2is?utm_source=unsplash&utm_medium=referral&utm_content=creditShareLink

FYI:

This Book is Banned participates in the Amazon.com affiliate program, where we earn a small commission by linking to books (but the price remains the same to you). This allows us to remain free, and ad free. [Our privacy policy]