Celebrating Ida B. Wells-Barnett

T

T

his Juneteenth, we celebrate Ida B. Wells-Barnett, whose lifelong crusade to make lynching a federal crime finally came to fruition on March 29, 2022 – 124 years and 21 presidents later.[1] Wells-Barnett was an educator, investigative journalist, and early civil rights activist during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[2]

Lamentably, it’s become exceedingly difficult to tell stories like Ida’s and make her writings known in American schools. Because more and more states are introducing legislation that restricts how teachers can discuss racism, sexism, and issues of systemic inequality in their classrooms.

Forty-four states have done so or have taken other steps that would limit how teachers can discuss these issues, since January 2021.[3]

And there’s a long history to this type of tactic – attempting to ban knowledge and control the historical narrative. During the days of slavery, it was illegal to teach enslaved persons to read – but secret schools were organized in hidden places at night.

During the Civil Rights movement, terror organizations like the KKK threatened organizers against spreading “dangerous” ideas – but organizers refused to capitulate.[4]

And today, extremist groups like Moms for Liberty threaten librarians with doxing or even gun violence for making books addressing racism in America accessible.[5]

But, it’s still be possible for young people to learn our nation’s true history. If not in school, from books, music, or on other avenues… websites like ThisBookisBanned.com, for example, whose organizers stand in solidarity with teachers and librarians facing this heinous legislation and threatened violence.[6]

Today, we’re seeing to it that Ida B. Wells-Barnett is celebrated. And, we’re doing our part to ensure that her anti-lynching campaign for racial justice doesn’t get swept under the proverbial rug – as much as the book banners at Moms for Liberty would like to see that happen.

Born into slavery

Ida Bell Wells was born into slavery on July 16,1862 in Holly Springs, Mississippi, and freed by the Emancipation Proclamation.[7] During the Reconstruction era, her parents were involved with politics and the democratization of education. Her father belonged to the Freedmen’s Aid Society, and helped start a school for newly freed enslaved people.[8]

Throughout her late teens, Ida was a teacher at Marshall and Tate County schools in rural Mississippi.[9] After her parents’ death, she and her siblings moved to Memphis, Tennessee to live with a relative.

At this time, she was hired by the Shelby County school system, and attended sessions at Fisk University – a historically Black college in Nashville – during her summer vacations. She also studied Lemoyne-Owen College – a historically Black college in Memphis.[10]

“I have a seat and I intend to keep it.”[11]

Decades before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a segregated bus in Montgomery, Alabama, Ida B. Wells (not yet Barnett) resisted giving up her seat on a passenger train going from Memphis to Woodstock, Tennessee. While Parks was arrested, Wells was not. She was, however, manhandled, and writes about the incident in her autobiography:

![]()

One day while riding back to my school I took a seat in the ladies’ coach of the train as usual. There were no jim crow cars then. But ever since the repeal of the Civil Rights Bill by the United States Supreme Court in 1877* there had been efforts all over the South to draw the color line on the railroads.

When the train started and the conductor came along to collect tickets, he took my ticket, then handed it back to me and told me that he couldn’t take my ticket there. I thought that if he didn’t want the ticket, I wouldn’t bother about it so went on reading. In a little while when he finished taking tickets, he came back and told me I would have to go in the other car. I refused, saying that the forward car was a smoker, and as I was in the ladies’ car I proposed to stay. He tried to drag me out of the seat, but the moment he caught hold of my arm I fastened my teeth in the back of his hand.

I had braced my feet against the seat in front and was holding to the back, and as he had already been badly bitten he didn’t try it again by himself. He went forward and got the baggage-man and another man to help him and of course they succeeded in dragging me out. They were encouraged to do this by the attitude of the white ladies and gentlemen in the car; some of them even stood on the seats so they could get a good view and continued applauding the conductor for his brave stand.

By this time the train had stopped at the first station. When I saw that they were determined to drag me into the smoker, which was already filled with colored people and those who were smoking, I said I would get off the train rather than go in… which I did. Strangely, I held onto my ticket all this time… [12]

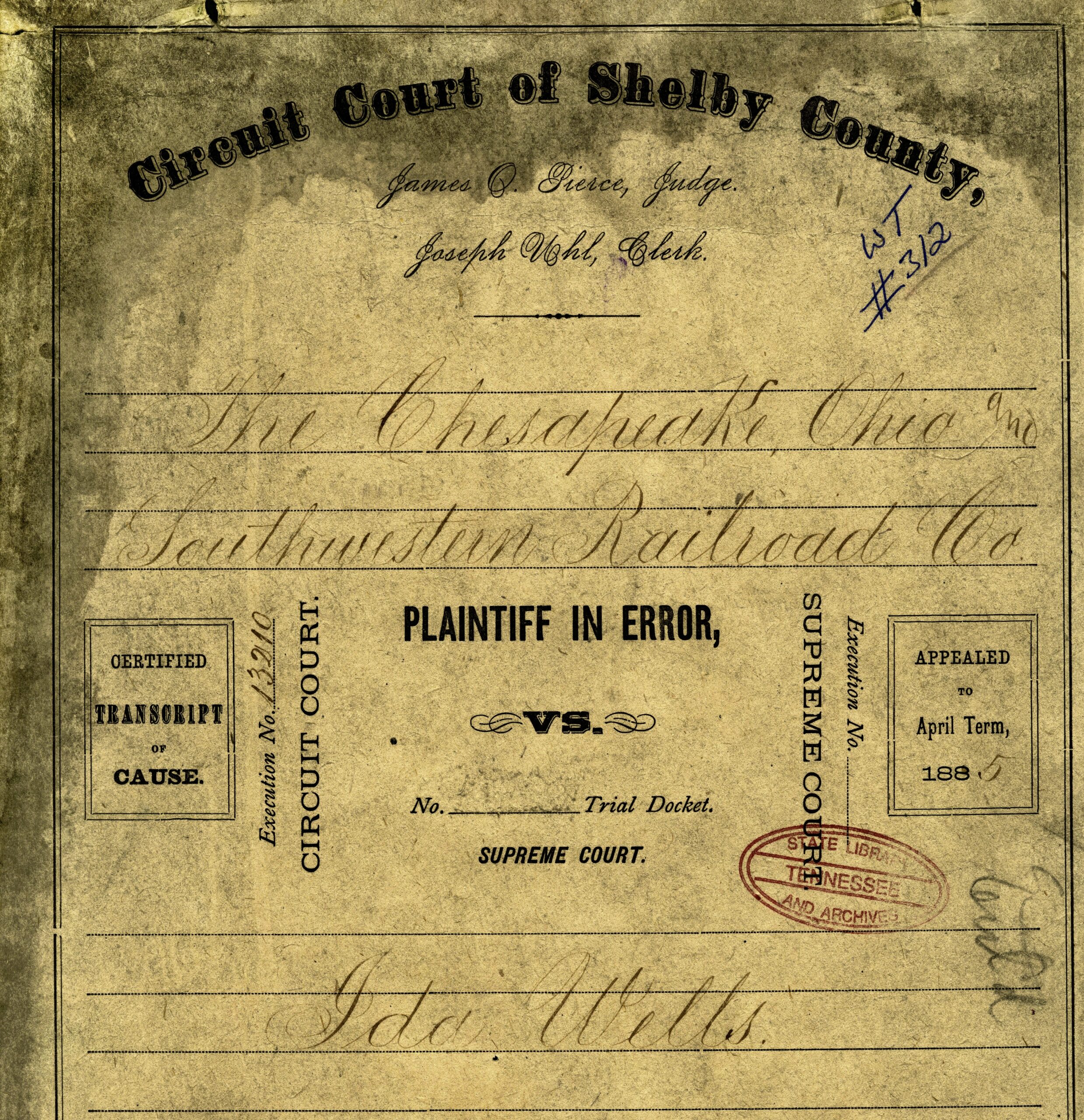

And then, she sued the Chesapeake, Ohio & Southwestern railroad company.[13] Surprisingly, the court decided in Wells’ favor, ordering the railroad company to pay damages. Needless to say, the railroad appealed the case to the Tennessee Supreme Court, and not so surprisingly, the decision was reversed. [14]

Suffragist and founding orgnaizer of the NAACP

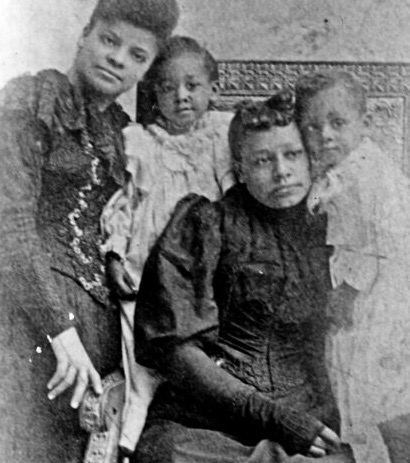

Years later, Ida B. Wells-Barnett was a founding organizer of the NAACP.[15] She was also instrumental in the establishment of the National Association of Colored Women’s Club, an organization which was created to address issues surrounding women’s suffrage and civil rights.[16]

As significant as these contributions are to civil rights and American history generally, Wells-Barnett’s name is most frequently associated with her campaign to make lynching a federal crime.

The Peoples Grocery Lynching

Just at the point when Wells-Barnett realized she could make a living from her newspaper, the Free Speech, the lynching that changed her life occurred. On March 9, 1892, she learned that Thomas Moss (whose daughter was her godchild), had been murdered – to be more precise, lynched – along with two of his employees, Calvin McDowell and Will Stewart.

Moss was a black man who owned Peoples Grocery, a successful grocery store in Memphis, Tennessee. As such, his store and its owner were seen as a threat by the white grocer whose store had served the community before Moss opened his.

The incident was sparked when a racially charged mob grew out of a fight between a Black and a white youth over a game of marbles near Moss’ grocery.

In short, adults got involved, violence ensued, and about 30 Black individuals were taken from their homes and jailed – among them Moss, McDowell, and Stewart, as well as the Black adolescent who was involved in the marble game that triggered the episode.

In the wee hours of the night, Moss, McDowell, and Stewart were dragged from their cells by 75 men, transported to a railroad yard outside the city’s limits, and shot to death. Given that Moss, McDowell, and Stewart were the only victims of this extralegal violence, there is little doubt that it was punishment for becoming an economic competitor to the white grocery store owner.[17]

Wells-Barnett was not in Memphis when this atrocity occurred. But, the leader in the Free Speech for that week called for the Black population to follow Moss’ dying words (reported in a newspaper the day after his death), “tell my people to go West – there is no justice for them here.”[18]

And, the Black community did just that. Within two months, six thousand people had abandoned Memphis. And, every type of business began to feel “this silent resentment of the outrage, and failure of the authorities to punish the lynchers.”[19]

On May 21, 1892, Ida B. Wells-Barnett published an impassioned editorial about the recent lynchings in the Free Speech. In response to her article, a mob burned down her press while she was attending a conference in New York City. And, her life was threatened if she were ever to return to Memphis.

In light of these threats, she remained in New York City until 1893, when she relocated to Chicago where she lived for the rest of her life. [20]

Her lifelong campaign begins

Wells-Barnett explicitly attributes the Peoples Grocery lynching with changing the course of her life. And, in response to the frequency of lynchings throughout the American South, she dedicated her life to documenting these horrific occurrences.

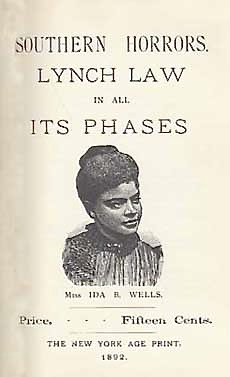

She published her research in a pamphlet titled Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases, prefacing this searing work with the words:

![]() It is with no pleasure I have dipped my hands in the corruption here exposed. Somebody must show that the Afro-American race is more sinned against than sinning, and it seems to have fallen upon me to do so.[21]

It is with no pleasure I have dipped my hands in the corruption here exposed. Somebody must show that the Afro-American race is more sinned against than sinning, and it seems to have fallen upon me to do so.[21]

Southern Horrors was the culmination of her intensive investigative work, providing eye-witness accounts, as well as statistics for lynchings reported in newspapers across both the South and the North.

It was groundbreaking, providing evidence that white men were rarely punished for sexual violence they perpetrated against Black women, while Black men were murdered by mobs for consensual sexual relations with white women.

She undermined the notion that lynchings were in response to rape, by pointing out that this accusation was levied at an unrealistic percentage of all victims. Wells-Barnett also challenged the fundamental assumption that it was only Black men who had been subject to lynchings. She revealed that Black women were also the victims of this heinous act.

In 1895, she published the first documented statistical report on lynching – A Red Record. With this book’s publication, she not only became one of the first prominent Black women journalists in the U.S., she was one of the first data reporters decades before the discipline formally existed.[22]

Ida B Wells-Barnett goes to The White House

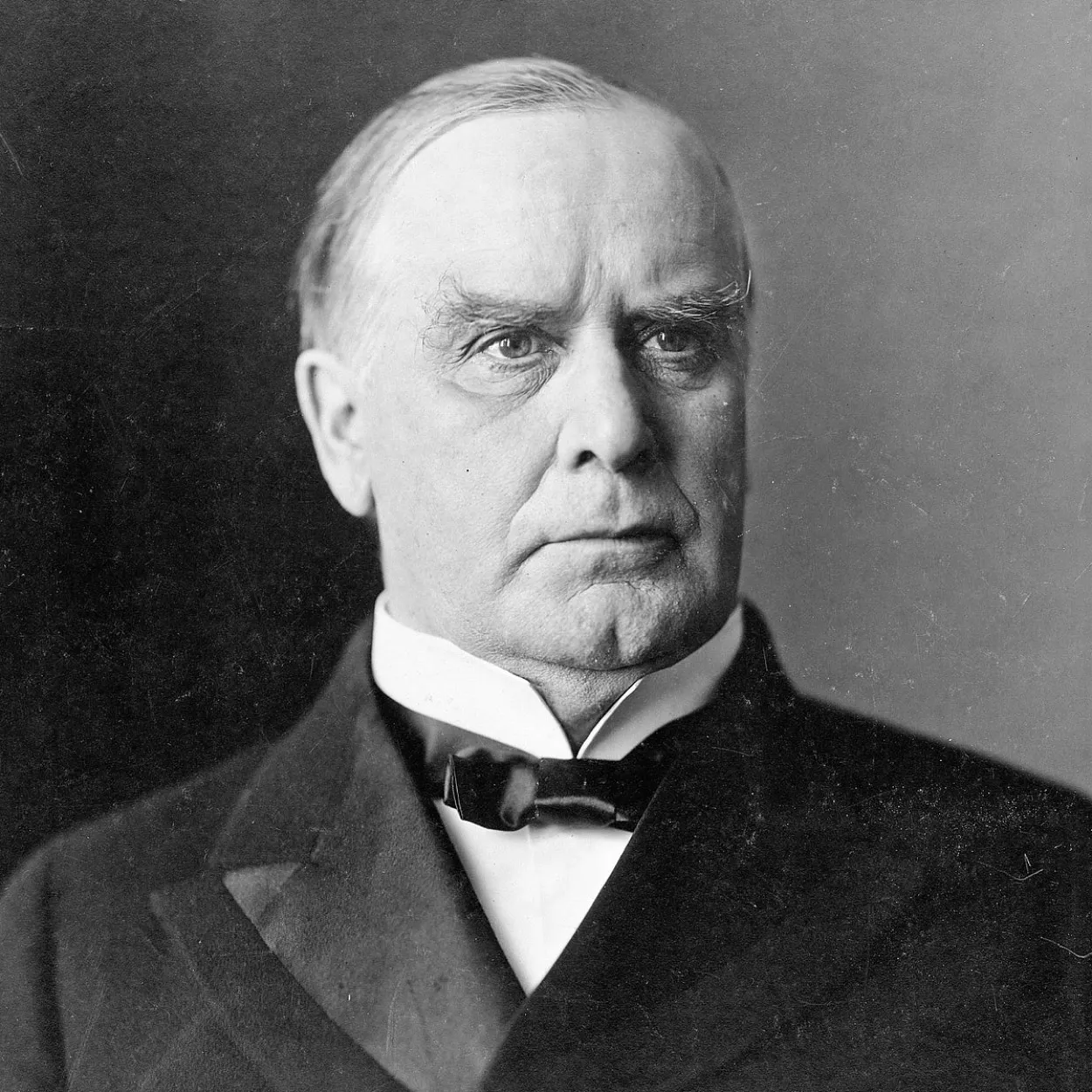

And, Wells-Barnett took her campaign to William McKinley’s White House. During her visit, she gave the president a petition appealing to him for national anti-lynching law, which stated:

![]() For nearly twenty years lynching crimes, which stand side by side with Armenian and Cuban outrages, have been committed and permitted by this Christian nation. Nowhere in the civilized world save the U.S. of America do men, possessing all civil and political power, go out in bands of 50 and 5,000 to hunt down, shoot, hang or burn to death a single individual, unarmed and absolutely powerless. Statistics show that nearly 10,000 American citizens have been lynched in the past 20 years. To our appeals for justice the stereotyped reply has been that the government could not interfere in a state matter. Postmaster Baker’s case was a federal matter, pure and simple. He died at his post of duty in defense of his country’s honor, as truly as did ever a soldier on the field of battle. We refuse to believe this country, so powerful to defend its citizens abroad, is unable to protect its citizens at home. Italy and China have been indemnified by this government for the lynching of their citizens. We ask that the government do as much for its own.[23]

For nearly twenty years lynching crimes, which stand side by side with Armenian and Cuban outrages, have been committed and permitted by this Christian nation. Nowhere in the civilized world save the U.S. of America do men, possessing all civil and political power, go out in bands of 50 and 5,000 to hunt down, shoot, hang or burn to death a single individual, unarmed and absolutely powerless. Statistics show that nearly 10,000 American citizens have been lynched in the past 20 years. To our appeals for justice the stereotyped reply has been that the government could not interfere in a state matter. Postmaster Baker’s case was a federal matter, pure and simple. He died at his post of duty in defense of his country’s honor, as truly as did ever a soldier on the field of battle. We refuse to believe this country, so powerful to defend its citizens abroad, is unable to protect its citizens at home. Italy and China have been indemnified by this government for the lynching of their citizens. We ask that the government do as much for its own.[23]

During the same period, she also lobbied Congress for the national anti-lynching law introduced by Illinois Congressman William E. Lorimer. But, to no avail on both fronts.

That didn’t stop her crusade, however. Wells-Barnett turned next to President Theodore Roosevelt, who merely addressed the issue through appeals to public morality and sentiment rather than actual federal reforms.

After that was President William Howard Taft, who wanted to leave the issue to the states but promised his personal support once his presidency was over. And, the anti-lynching campaign got even less aid during President Woodrow Wilson’s administration.

President Warren G. Harding supported the Anti-Lynching Bill that was introduced in Congress during the Wilson administration but had been halted by filibuster. And, he delivered a speech that condemned lynching. But public response was largely negative, indicating the difficult road that lay ahead for anti-lynching activists.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett died on March 25, 1931, in Chicago, Illinois. Though lynching still raged and the legacy of her tireless dedication was not fully realized, her activism was instrumental in establishing the space for future discussion to take place.[24]

On May 4, 2020, she was posthumously awarded the Pulitzer Prize, “for her outstanding and courageous reporting on the horrific and vicious violence against African Americans.”[25]

Finally, on March 29, 2022, President Joe Biden signed the anti-lynching measure she had worked so hard to make happen into law, rendering lynching a federal hate crime.[26]

So, we’re celebrating Ida B. Wells-Barnett in observance of Juneteenth. And, to help keep her story alive, here are some of her works to download. [Be advised, given the subject matter this material contains disturbing images and accounts of violence]:

Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All its Phases.

Eye-witness accounts of lynchings reported in newspapers

across both the South and the North.

A Red Record.

The first documented statistical report on lynching.

Mob Rule in New Orleans.

An examination of the dynamics of racial violence

and lynching during the Jim Crow Era.

And for all you educators out there, here’s a lesson plan to download,

Ida B. Wells and the Long Crusade to Outlaw Lynching,

designed by RetroReport, a fabulous source for classroom resources.

Share This Post, Choose a Platform!

Endnotes:

[1] “Ida B. Wells and the Long Crusade to Outlaw Lynching.” February 15, 2024. RetroReport.org

https://retroreport.org/has-lesson-plan/ida-b-wells-and-the-long-crusade-to-outlaw-lynching-2/?utm_source=Retro+Report+Education&utm_campaign=c212e1f834-MAR11_DOUBLEV_COPY_01&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_64a84ba2bf-c212e1f834-357769000&mc_cid=c212e1f834&mc_eid=bd14da2bcd

[2] “Letter from Ida B. Wells-Barnett to President Woodrow Wilson.” March 26, 1918. DocsTeach from the National Archives. https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/ida-b-wells-wilson

[3] Schwartz, Sarah. “Map: Where Critical Race Theory Is Under Attack.” June 6, 2024. EducationWeek. https://www.edweek.org/policy-politics/map-where-critical-race-theory-is-under-attack/2021/06

[4] IBWEP Statement on Recent Attacks Against Critical Race Theory in Schools.” The Ida B. Wells Education Project Blog. https://www.idabwellseducationproject.org/ibwep-blog

[5] Altschuler, Glenn C. “Six reasons why Moms for Liberty is an extremist organization.” July 9, 2023. The Hill. https://thehill.com/opinion/education/4086179-six-reasons-why-moms-for-liberty-is-an-extremist-organization/

[6] IBWEP Statement on Recent Attacks Against Critical Race Theory in Schools.” The Ida B. Wells Education Project Blog. https://www.idabwellseducationproject.org/ibwep-blog

[7] Norwood, Arlisha R. “Ida B. Wells. Barnett.” National Women’s History Museum. https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/ida-b-wells-barnett

[8] Levesque, Faron. “Ida B. Wells and People’s Grocery.” The MIT Press Reader. https://thereader.mitpress.mit.edu/ida-b-wells-and-peoples-grocery/

Heather-Lea, Patricia. “Ida Wells an inspiring heroine for international Women’s Day.” Addison County Independent. https://web.archive.org/web/20201104023730/https://addisonindependent.com/letter-editor-ida-wells-inspiring-heroine-international-womens-day

[9] Bay, Mia. To Tell the Truth Freely: The Life of Ida B. Wells. New York: Hill and Wang, a division of Farraar, Strauss and Tiroux, 2009. Pg 34.

[10] Levesque, Faron. “Ida B. Wells and People’s Grocery.” The MIT Press Reader. https://thereader.mitpress.mit.edu/ida-b-wells-and-peoples-grocery/

[11]“Chesapeake, Ohio & Southwestern Railroad Company v Ida B. Wells.” Digital Public Library of America. https://dp.la/primary-source-sets/ida-b-wells-and-anti-lynching-activism/sources/1113

[12] Wells, Ida B. Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells. Edited by Alfreda M. Duster. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press,1970. Pg 18-19.

*The Civil Rights Act of 1875 was, among other things, designed to provide all citizens regardless of color access to public accommodations. Wells was in error, however, about the date when this act was held unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court. That actually occurred in 1883.

[13] “A legal brief for Ida B. Wells’ lawsuit against Chesapeake, Ohio, and Southwestern Railroad Company before the state Supreme Court, 1885.” Digital Public Library of America.

https://dp.la/primary-source-sets/ida-b-wells-and-anti-lynching-activism/sources/1113

[14] “A legal brief for Ida B. Wells’ lawsuit against Chesapeake, Ohio, and Southwestern Railroad Company before the state Supreme Court, 1885.” Digital Public Library of America.

https://dp.la/primary-source-sets/ida-b-wells-and-anti-lynching-activism/sources/1113

[15] Sullivan, Patricia. Lift Every Voice: The NAACP and the making of the Civil Rights movement. New York: The New Press, 2009.

[16] Norwood, Arlisha R. “Ida B. Wells. Barnett.” National Women’s History Museum. https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/ida-b-wells-barnett

[17] Mitchell, Damon. “The People’s Grocery Lynching, Memphis, Tennessee.” Jstor Daily. January 24, 2018. https://daily.jstor.org/peoples-grocery-lynching/

Wells, Ida B. “Lynch Law in all its Phases.” February 13, 1893. Voices Of Democracy: The U.S. Oratory Project. https://voicesofdemocracy.umd.edu/wells-lynch-law-speech-text/

[18] Wells, Ida B. Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells. Edited by Alfreda M. Duster. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press,1970. Pg 50-51.

[19] Wells, Ida B. “Lynch Law in all its Phases.” February 13, 1893. Voices Of Democracy: The U.S. Oratory Project. https://voicesofdemocracy.umd.edu/wells-lynch-law-speech-text/

[20] Mobley, Tianna. “Ida B. Wells-Barnett: Anti-lynching and the White House.” The White House Historical Association. https://www.whitehousehistory.org/ida-b-wells-barnett-anti-lynching-and-the-white-house

Little, Becky. “When Ida B. Wells Took on Lynching, Threats Forced Her to Leave Memphis.” May 18, 2023. History.com https://www.history.com/news/ida-b-wells-lynching-memphis-chicago

[21] Wells-Barnett, Ida B. Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases. New York: The New York Age Print, 1892.

[22] Mobley, Tianna. “Ida B. Wells-Barnett: Anti-lynching and the White House.” The White House Historical Association. https://www.whitehousehistory.org/ida-b-wells-barnett-anti-lynching-and-the-white-house

[23] Cleveland Gazette, 9 April 1898. Reprinted in Herbert Aptheker, ed., A Documentary History of the Negro People in the United States, 2, (The Citadel Press: New York, 1970), 798. https://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/56

[24] Mobley, Tianna. “Ida B. Wells-Barnett: Anti-lynching and the White House.” The White House Historical Association. https://www.whitehousehistory.org/ida-b-wells-barnett-anti-lynching-and-the-white-house

[25] “Ida B. Wells,” Special Citations and Awards (The Pulitzer Prizes, 2020) . https://www.pulitzer.org/winners/ida-b-wells

[26] “Remarks by President Biden at Signing of H.R. 55, the ‘Emmett Till Antilynching Act.’” March 29, 2020. The White House. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2022/03/29/remarks-by-president-biden-at-signing-of-h-r-55-the-emmett-till-antilynching-act/

Images:

Ida B. Wells-Barnett: Ida B. Wells Papers, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

Born into Slavery: Historic Charleston.org https://www.historiccharleston.org/research/photograph-collection/detail/slave-cabin-with-child-in-doorway/8C433E91-F909-47F7-AF1F-459819142111

I have a seat and I intend to keep it: Digital Public Library of America. https://dp.la/primary-source-sets/ida-b-wells-and-anti-lynching-activism/sources/1113

Suffragist and founding organizer of the NAACP: Capper’s Weekly (Topeka, Kansas) 01 August 1914, pg. 3.

The Peoples Grocery Lynching: Thomas Moss family-Ida B. Wells Papers, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library

Her lifelong campaign begins: Cover of Southern Horrors. Public Domain.

Ida B Wells-Barnett goes to The White House: President William McKinley.https://www.whitehouse.gov/about-the-white-house/presidents/william-mckinley/

Juneteenth Flag: Lisa Jeanne Graf, who modified the original Juneteenth flag created in 1997 by Ben Haith, the founder of the National Juneteenth Observance Foundation. Alvarez, Beatrice. “What Does Juneteenth Celebrate? The History of the Holiday.” PBS, 15 June 2022, www.pbs.org/articles/learn-about-and-celebrate-juneteenth/.