W

W

hat’s up with the brouhaha that perpetually revolves around this book? Salinger was writing within the most American of literary forms, the jeremiad.

Why was The Catcher in the Rye banned? In short, Salinger’s work challenged the status quo. And it did so in an era defined by conformity. So, the outcome is pretty predictable. As a New York Times columnist once put it, The Catcher in the Rye has been “yanked out of American schools more than almost any other title.”[1] And the challenges come fast and furious.

The earliest attempt to remove The Catcher in the Rye from high school reading materials occurred in 1954, and took place in Marin County, California. Shortly after that, a similar effort was made to restrict students’ reading of the book in Los Angeles County. The following year, it was censored in Baltimore, Boston, Buffalo, and Port Huron as well. In 1956, a group known as The National Organization for Decent Literature labeled The Catcher in the Rye objectionable.[2] At this point, Catcher had also been banned in Fairmont, McMechen, St. Louis, and Wheeling, West Virginia. Efforts to ban Salinger’s work continued to expand.[3]

.

And the hits just keep on coming.

Between 1961 and 1965, there were eighteen separate attempts to ban The Catcher in the Rye from high school campuses, creating enough controversy to draw the attention of national newspapers.[4] But challenges haven’t been limited to the decades immediately following the novel’s publication – the hits just keep on coming! According to the office of Intellectual Freedom, the novel is “a perennial No. 1 on the censorship hit list,” and has remained on the American Library Association’s annual Banned Book report well into the 21st century.[5]

_________

What’s the rub, anyway?

Why is The Catcher in the Rye so controversial? Attacks on Catcher revolve around a number of concerns. Grievances usually have to do with language challengers consider offensive – one parent cited 785 “profanities.”[6] Objections frequently involve blasphemy. Or a general “family values” kind of complaint, like the undermining of parental authority. To top things off, Holden Caulfield’s criticism of “home life, [the] teaching profession, religion, and so forth” was summed up as an assault on patriotism, with Catcher labeled downright un-American.[7] Holden Caulfield, challengers charge, is quite simply not a good role model for teen-age readers.[8]

But, is Salinger’s protagonist intended to be a role model? If these concerned citizens realized that literature is a powerful platform for examining societal ills, they would have understood that depicting such behavior doesn’t necessarily mean the author is endorsing it. In fact, quite the opposite. When read merely for plot, The Catcher in the Rye appears to be nothing more than the story of a teenage boy having trouble transitioning to adulthood. However, the inappropriate behavior Holden Caulfield engages in, and the way he expresses himself have a rhetorical purpose. And when read accordingly, they reflect the shifting societal landscape Salinger sees in postwar America. Holden is grappling with the same kinds of questions the challengers’ own children are facing. Holden Caulfield is not, in fact, intended to be a role model. Because Salinger’s work is about much more than the antics of a rebellious teenager.

Given the kinds of complaints behind the banning of Salinger’s novel, it is no surprise that one of its challenges was led by a woman who had not read, and declared she would never read, The Catcher in the Rye.[9] What is surprising is that someone who hasn’t even read a particular book has the capacity to restrict others’ access to it.

What these censors fail to realize is that there’s more to The Catcher in the Rye than “Holden Caulfield is a bad boy with a potty mouth.” Having said that, why is Catcher important? And what’s Holden is so cranked up about in the first place? Come to find out, Holden Caulfield is a twentieth-century Jeremiah._________

Holden Caulfield:

Twentieth-century Jeremiah.

During the post-World War II period when popular culture was trumpeting American ideals, Salinger was writing about the realities of the social experience in America, those obscured by a society consumed with image and material goals. Though The Catcher in the Rye has resonated with teenage readers as an expression of adolescent alienation for generations, it isn’t just about raging against the establishment. As Salinger’s biographers note, he was “not just another nihilist; and Holden [is] not just another lost boy.”[10] When read for more than plot, both the book and the boy exhibit a spiritual nature. Holden isn’t just running away from adulthood. He seeks to transcend a materially obsessed culture.

Salinger didn’t set out to write an anti-American diatribe, as The Catcher in the Rye has been labeled by those attempting to ban it. He was actually writing within the most American of literary forms, the jeremiad, to convey a message of reform. The jeremiad is a rhetorical method that was named for the prophet Jeremiah and used by the Puritans, one designed to keep American society in line with its ideals by calling attention to its flaws.[11]

An essential fact about The Catcher in the Rye, is that Holden does not reject historically American values. What he does is criticize the flawed way they’re enacted in modern society, and berate the replacement of morality with conformity.[12] As his sister Phoebe points out to him, Holden has the Robert Burns line of poetry wrong, an incorrect recollection that gives us the novel’s title: it’s “if a body meet a body,” rather than “if a body catch a body.” What Holden’s misremembering tells us is that he’s not “looking for love in all the wrong places,” but as with all “Jeremiahs” (and maybe a few bullfrogs), he wants to save society from a corrupt and deteriorating culture.[13]

_______

It’s about more than teen-age angst.

On its face, The Catcher in the Rye is about an immature teenage boy unable to come to terms with his impending adulthood. And more often than not, it is this perspective that’s taught in schools. Sure, high school students can relate to that narrative. But “life is hard, and Holden needs to get himself together,” is a cursory reading of the novel at best.

The book has also been described as “a story about a boy whose little brother has died,” with Holden’s negative perspective on the world seen as a manifestation of his grief.[14] This interpretation does indeed delve beneath the surface narrative. And it is enlightening. But there’s still more to Catcher than the psychology behind Holden’s actions.

Others have read Salinger’s work through the lens of his World War II-induced Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. But, what’s the point of writing that book? For therapeutic purposes, perhaps? Holden’s exchange with Mr. Antolini suggests such a possibility, that he may be able to help himself by helping others with his novel. It is true that we are all “broken” in one way or another, and Catcher is most certainly relatable on that level. But, the self-imposed exile Salinger is so famous for suggests a purpose other than reaching out to other “irreparably damaged” people with a healing message.[15]

I would argue that The Catcher in the Rye is a re-fashioned jeremiad. Not only because this interpretation considers the author and his historical context, but because, as Lionel Trilling points out, “literary situations [are] cultural situations.”[16] Understanding Salinger’s work as a jeremiad takes “the animus of the author” into account.[17] That is, what he wants to see happen as a result of people reading his book.

_________

What the heck is a Jeremiad?

Considered America’s first distinct literary genre, the jeremiad is a political sermon that, as mentioned above, takes its tone from the biblical prophet Jeremiah. It’s a mode of public exhortation used by the New England Puritans through the close of the eighteenth century for the purpose of social revitalization. In other words, the American jeremiad is a call for America to self-correct.[18]

These days, in industrialized societies like ours, it’s genres such as film, popular music, and literature that serve to expose injustices, inefficiencies, and immoralities in social structures. These modes influence culture by getting us to think about the shortcomings in our society. This leads to new insights, which in turn take root and reshape cultural expectations.[19]

_________

There’s a long history of literature as jeremiad.

Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye belongs to a lineage of American writers who have inherited and re-fashioned the jeremiad genre, authors who produced literature thick with spiritual protest.[20] Harriett Beecher Stowe’s abolitionist novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, for example, lambastes the country’s great sin of slavery, (and resulted in active resistance to the Fugitive Slave Act).[21] Henry David Thoreau’s essay Life Without Principle decries America’s narrow focus on making money, as well as the superficial nature of media, that “blunt[s]” a person’s sense of what is right.[22] Then there’s John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath, which laments the widespread foreclosures and subsequent homelessness caused by the “double whammy” of the Depression and the Dust Bowl. This work takes aim at “American greed, waste, and spongy morality.[23] And the lineage continues right up through Salinger and beyond.

Given Holden Caulfield’s constant judgement of the world as he sees it, The Catcher in the Rye is nothing if not the “catalogue of iniquities” inherent to the jeremiad form.[24] Interestingly, the fact that Catcher’s critique of mainstream American goals has led to it being labeled “un-American” parallels the history of the American jeremiad itself.[25]

The Puritans failed to realize how their self-denunciations would sound to non-New England ears. And they were nothing short of shocked when others took their jeremiads at face value, which prompted leaders from competing charters to proclaim New England “a sink of iniquity.”[26] Bearing this in mind, it became necessary to explain that the jeremiad was a rhetorical exercise, intended as motivation to live up to American ideals.

A similar reproach is echoed in Sinclair Lewis’ declaration, “I love America… I love it, but I don’t like it,” a sentiment that also runs through the following passage from The Catcher in the Rye[27]:

But you’re wrong about that hating business. I mean about hating football players and all. You really are. I don’t hate too many guys. What I may do, I may hate them for a little while, like this guy Stradlater I knew at Pencey, and this other boy, Robert Ackley. I hated them once in a while – I admit it – but it doesn’t last too long, is what I mean. After a while, if I didn’t see them, if they didn’t come in the room, or if I didn’t see them in the dining room for a couple of meals, I sort of missed them. I mean I sort of missed them.[28]

Though Holden does indeed lambaste his classmates, as this passage shows he doesn’t carry any ongoing animosity toward them, or football players generally. Rather, his indictments call out particular behaviors commonplace in the larger society.

_________

What makes Holden Caulfield a “Jeremiah”?

Holden expresses a fear that he’s disappearing as he crosses from one side of the road or street to the other, an image that bookends the narrative. This symbolizes his sense of diminishing authenticity within American society. As Perry Miller argues in his work on the American jeremiad, since the days of Jonathan Edwards (a fiery eighteenth-century minister referred to as the last Puritan), western civilization has put reflections about the larger meaning of existence aside.[29] We have distracted ourselves with materialism and concerns for image, pursuits that do nothing to address the ills of society. And it is this demise of American ideals that Allie Caulfield’s death signifies, an interpretation underscored by Holden’s prophetic appeal, “Allie, don’t let me disappear,” when crossing the street toward the end of the novel.[30]

And, Holden Caulfield’s iconic red hunting hat is the most important symbol in The Catcher in the Rye. It alludes to the “hunters” mentioned in the book of Jeremiah, invading nations invoked as divine retribution for Israel’s failure to heed the prophet’s warnings.[31] The hat’s color is significant because red is the traditional color of forewarning, or signaling alarm. Fire trucks and ambulance lights both flash red, as do those at railroad crossings. In keeping with what the hat symbolizes, Holden’s reference to it as a “people hunting hat” indicates that he is “taking aim” as it were, to expose their hypocrisy and “phoniness.” To read it as a call for actual violence is a failure to engage the novel’s symbolic language. Needless to say, no one escapes Holden’s critical eye.

_________

What are Holden’s Puritanical ideals?

Though the fervor of Holden’s accusations is typically attributed to him being a “disaffected teen,” his targets align with themes common in the colonial pulpit, specifically, being tempted by profits and pleasures, false dealing with God, and the corruption of children.[32]

Regarding profits, Holden makes it very clear that he considers his older brother to have sold-out. D. B. used to write short stories, including Holden’s favorite about a boy so proud of buying a goldfish with his own money, that he wouldn’t let anyone else see it. But now, D. B.’s a Hollywood screenwriter who buys extravagant cars for all to see. These days, it’s more about greed and image than writing good stories.[33]

The Christmas pageant at Radio City also takes a hit. The holiday has been reduced to nothing more than a means of chasing profit. Angels emerge from gift-wrapped boxes, and “guys carrying crucifies and stuff all over the place,” all while singing Oh, Come All Ye Faithful. In typical irreverent fashion, Holden calls out the crass commercialization of a subject that should be approached with reverence and respect, proclaiming “Jesus probably would’ve puked if He could see it—all those fancy costumes and all.”[34]

Holden specifically addresses false dealing with God in a story revolving around Ossenburger, a Pencey donor speaking at a school event. Ossenburger is an alumnus who “made a pot of dough in the undertaking business” with a nation-wide franchise of cut-rate funeral parlors, sufficient wealth to bankroll the dormitories commemorated with his name. During school chapel, Ossenburger urges students to talk to Jesus all the time, which he himself does (or so he says), even while driving his Cadillac. Holden’s remark about Ossenburger “shifting into first gear and asking Jesus to send him a few more stiffs,” targets hypocritical relationships with God, those based on show rather than piety and service.[35]

And where pleasures are concerned, unlike his “unscrupulous” classmate Stadlater who doesn’t even remember his dates’ names correctly, Holden aspires to spend time with girls he can relate to on an emotional or intellectual level. [36] Preferring a well-rounded relationship, Holden states, “If you really don’t like a girl, you shouldn’t horse around with her at all.”[37]

The corruption of children is a particular hotspot for Holden Caulfield. Discovering obscene graffiti on the wall of his sister’s grade school drives him “damn near crazy.” He is irate thinking about how “some dirty kid” would tell Phoebe and her classmates what the offensive phrase means. And how, given their young age, the act portrayed would be confusing and nothing less than disturbing.[38]

The very name of Salinger’s book refers to Holden’s need to protect “little kids.” But how so, what does the title of The Catcher in the Rye mean? In the context of the titular metaphor, he envisions himself patrolling a field of rye, and catching the children who are playing there should they start to go over the “crazy cliff,” typically understood as adulthood.[39] From Holden’s prophetic view, adulthood would require the corruption of these children to be in line with a degraded society, consumed with image and material goals rather than traditional American ideals.

_________

The Jeremiad: Not just an

“Undying Monotonous Wail.”[40]

Despite its catalogue of iniquities, the American jeremiad’s distinctiveness doesn’t lie in the intensity of its complaint, but precisely the opposite. At the heart of this genre is an unwavering optimism in the American ideal. Which, as scholar Sacvan Bercovitch maintains, grows more emphatic “from one generation to the next.”[41]

Which is why Phoebe Caulfield enters the picture when she does. She embodies the “next” generation Bercovitch is referring to. The fact that Phoebe is the only character throughout the novel who actually listens to what Holden has to say is significant, in that she’s the one who “hears” his prophetic message.[42] And Holden allows her to wear his hunting hat, which establishes Phoebe as successor to Holden’s mission. Finally, Holden literally sets Phoebe in motion with a ticket for the carousel, where she optimistically sets her sights on the golden ring, an obvious symbol for the American ideal. The proverbial torch has been passed, with Phoebe carrying Holden’s mission forward.

_________

In Conclusion.

Reading The Catcher in the Rye as a re-fashioned jeremiad, we understand that Salinger’s intent was not to malign America. Very far from it. Like the Puritan jeremiads whose message was also misunderstood, Catcher urges America to remember the ideals on which it was founded, principles we appear to have forgotten, and to self-correct. What Salinger hoped to accomplish is that the readers of his novel would make that happen. But like the question of whether or not Holden will apply himself in school next year, it’s up to us to engage the endeavor.

Endnotes:

[1] Quindlen, Anna. “Public & Private; Dirty Pictures.” The New York Times. April 22, 1990.

[2] Whitfield, Stephen J. “Cherished and Cursed: Toward a Social History of the Catcher in the Rye.” The New England Quarterly, Vol. 70, No. 4 (Dec., 1997), 575.

[3] Steinle, Pamela Hunt. In Cold Fear: The Catcher in the Rye Censorship Controversies and Postwar American Character. (Columbus: Ohio State University, 2002), 73, 52.

[4] Steinle, 61.

[5] Mydans, Seth. “In a Small Town, a Battle Over a Book.” The New York Times, (Sept. 3, 1989).

[6] Whitfield, 575.

[7] Laser, Marvin and Fruman, Norman. “Not Suitable for Temple City.” in Studies in J. D. Salinger: Reviews, Essays, and Critiques of The Catcher in the Rye, and other Fiction. Edited by Marvin Laser and Norman Fruman. (New York: The Odyssey Press, 1963), 127.

[8] Mydans.

[9] Mydans.

[10] Shields, David and Salerno, Shane. Salinger. (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2013), 265.

[11] Bercovitch, Sacvan. The American Jeremiad. (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2012), xli; Miller, Perry. Errand Into the Wilderness. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1984), 10.

[12] Steinle, Pamela. “If a Body Catch a Body: The Catcher in the Rye Censorship Debate as Expression of Nuclear Culture.” Popular Culture and Political Change in Modern America. Contemporary Literary Criticism. Vol. 138, 2001.

[13] Mallette, Wanda; Morrison, Bob; Ryan, Patti. “Lookin’ for Love.” Urban Cowboy Soundtrack. (Hollywood: Full Moon, 1980); Shields and Salerno, 265.

[14] Menard, Louis. “Holden at Fifty: The Catcher in the Rye and what it spawned.” The New Yorker. (September 24, 2001).

[15] Shields and Salerno, 243.

[16] Trilling, Lionel. “On the Teaching of Modern Literature.” First published as “On the Modern Element in Modern Literature.” Partisan Review, January-February 1961.

[17] Trilling.

[18] Bercovitch, Sacvan. The American Jeremiad. (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2012), xli; Miller, Perry. Errand Into the Wilderness. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1984), 10.

[19] Turner, Victor. From Ritual to Theatre: The Human Seriousness of Play. (New York: Performing Arts Journal Publications, 1982), 40-45; Turner, Victor. “Liminal to Liminoid, in Play, Flow, and Ritual: An Essay in Comparative Symbology.” Rice Institute Pamphlet – Rice University Studies, 60, no. 3 (1974), 71.

[20] Bercovitch, Sacvan. The Rites of Assent: Transformations in the symbolic Construction of America. (New York: Routledge, 1993), 18.

[21] Senior, Nassau William. American Slavery: A Reprint of an Article on “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” (London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans & Roberts, 1856), 2.

[22] Thoreau, Henry David. Life Without Principle. (London: The Simple Life Press, 1905), 29.

[23] Shillinglaw, Susan. “John Steinbeck, American Writer.” The Steinbeck Institute.

[24] Tolchin, Karen R. Part Blood, Part Ketchup: Coming of Age in American Literature and Film. (New York: Lexington Books, 2007), 38; Bercovitch (2012), 6-7.

[25] Laser, Marvin and Fruman, Norman. “Not Suitable for Temple City.” in Studies in J. D. Salinger: Reviews, Essays, and Critiques of The Cather in the Rye, and other Fiction. Edited by Marvin Laser and Norman Fruman. (New York: The Odyssey Press, 1963), 127.

[26] Miller, Perry. The New England Mind: From Colony to Province. (London: The Belknap Press, 1981), 173-174.

[27] Miller, Perry. “The Incorruptible Sinclair Lewis.” The Responsibility of Mind in a civilization of machines. Edited by John Crowell and Stanford J. Searl, Jr. (Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press, 1979), 121.

[28] Salinger, J.D. The Catcher in the Rye. (New York: Little Brown and Co., 1991), 187.

[29] Rowe, Joyce. “Holden Caulfield and American Protest.” In New Essays on The Catcher in the Rye. Edited by Jack Salzman. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 88; Van Engen, Abram C. City on a Hill. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020), 248; Brand, David C. Profile of the Last Puritan: Jonathan Edwards, Self-love, and the Dawn of the Beatific. (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1991).

[30] Salinger, 198.

[31] Ellicott’s Commentary for English Readers. https://biblehub.com/commentaries/jeremiah/16-16.htm; The New Oxford Annotated Bible. Edited by Michael D. Coogen. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), Jeremiah 3:12-23, Jeremiah 27, Jeremiah 6:13.

[32] Tolchin, 41; Bercovitch (2012), 4.

[33] Salinger, 16.

[34] Salinger, 137.

[35] Salinger, 16.

[36] Salinger, 31.

[37] Salinger, 62.

[38] Salinger, 201.

[39] Salinger, 173.

[40] Bercovitch (2012), 5.

[41] Bercovitch (2012), 6.

[42] Moore, Robert P. “The World of Holden.” The English Journal. Vol. 54, No. 3 (March 1965), 160.

Images:

.

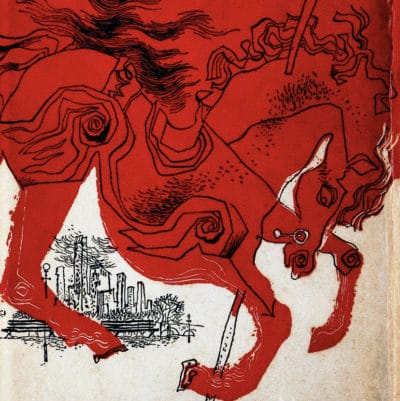

1 The Catcher in the Rye cover from the 1985 Bantam edition. Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Catcher-in-the-rye-red-cover.jpg Cropped by User.

2 Rembrandt van Rijn. Jeremiah Lamenting the Destruction of Jerusalem. 1630. Public Domain via Rijkjsmuseum.nl/nl http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.5242

3 Cotton Mather. By Peter Pelham, artist – http://www.columbia.edu/itc/law/witt/images/lect3/, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=80525

4 Holden Caulfield’s red hunting hat. Clipartmax.com https://www.clipartmax.com/png/middle/121-1213961_the-red-hunging-hat-2-discussion-posts-kate-said-red-hunting-hat.png (The original image has been flopped.)

5 First-edition cover of The Catcher in the Rye (1951). Public Domain. Source, Nate D. Sanders auctions (direct link to jpg) via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Catcher_in_the_Rye_

(1951,_first_edition_cover).jpg

Original image retouched by uploader, and cropped by current user.

The Catcher in the Rye: A Twentieth-century Jeremiad

hat’s up with the brouhaha that perpetually revolves around this book? Salinger was writing within the most American of literary forms, the jeremiad.

Why was The Catcher in the Rye banned? In short, Salinger’s work challenged the status quo. And it did so in an era defined by conformity. So, the outcome is pretty predictable. As a New York Times columnist once put it, The Catcher in the Rye has been “yanked out of American schools more than almost any other title.”[1] And the challenges come fast and furious.

The earliest attempt to remove The Catcher in the Rye from high school reading materials occurred in 1954, and took place in Marin County, California. Shortly after that, a similar effort was made to restrict students’ reading of the book in Los Angeles County. The following year, it was censored in Baltimore, Boston, Buffalo, and Port Huron as well. In 1956, a group known as The National Organization for Decent Literature labeled The Catcher in the Rye objectionable.[2] At this point, Catcher had also been banned in Fairmont, McMechen, St. Louis, and Wheeling, West Virginia. Efforts to ban Salinger’s work continued to expand.[3]

.

And the hits just keep on coming.

Between 1961 and 1965, there were eighteen separate attempts to ban The Catcher in the Rye from high school campuses, creating enough controversy to draw the attention of national newspapers.[4] But challenges haven’t been limited to the decades immediately following the novel’s publication – the hits just keep on coming! According to the office of Intellectual Freedom, the novel is “a perennial No. 1 on the censorship hit list,” and has remained on the American Library Association’s annual Banned Book report well into the 21st century.[5]

_________

What’s the rub, anyway?

Why is The Catcher in the Rye so controversial? Attacks on Catcher revolve around a number of concerns. Grievances usually have to do with language challengers consider offensive – one parent cited 785 “profanities.”[6] Objections frequently involve blasphemy. Or a general “family values” kind of complaint, like the undermining of parental authority. To top things off, Holden Caulfield’s criticism of “home life, [the] teaching profession, religion, and so forth” was summed up as an assault on patriotism, with Catcher labeled downright un-American.[7] Holden Caulfield, challengers charge, is quite simply not a good role model for teen-age readers.[8]

But, is Salinger’s protagonist intended to be a role model? If these concerned citizens realized that literature is a powerful platform for examining societal ills, they would have understood that depicting such behavior doesn’t necessarily mean the author is endorsing it. In fact, quite the opposite. When read merely for plot, The Catcher in the Rye appears to be nothing more than the story of a teenage boy having trouble transitioning to adulthood. However, the inappropriate behavior Holden Caulfield engages in, and the way he expresses himself have a rhetorical purpose. And when read accordingly, they reflect the shifting societal landscape Salinger sees in postwar America. Holden is grappling with the same kinds of questions the challengers’ own children are facing. Holden Caulfield is not, in fact, intended to be a role model. Because Salinger’s work is about much more than the antics of a rebellious teenager.

Given the kinds of complaints behind the banning of Salinger’s novel, it is no surprise that one of its challenges was led by a woman who had not read, and declared she would never read, The Catcher in the Rye.[9] What is surprising is that someone who hasn’t even read a particular book has the capacity to restrict others’ access to it.

What these censors fail to realize is that there’s more to The Catcher in the Rye than “Holden Caulfield is a bad boy with a potty mouth.” Having said that, why is Catcher important? And what’s Holden is so cranked up about in the first place? Come to find out, Holden Caulfield is a twentieth-century Jeremiah._________

Holden Caulfield:

Twentieth-century Jeremiah.

During the post-World War II period when popular culture was trumpeting American ideals, Salinger was writing about the realities of the social experience in America, those obscured by a society consumed with image and material goals. Though The Catcher in the Rye has resonated with teenage readers as an expression of adolescent alienation for generations, it isn’t just about raging against the establishment. As Salinger’s biographers note, he was “not just another nihilist; and Holden [is] not just another lost boy.”[10] When read for more than plot, both the book and the boy exhibit a spiritual nature. Holden isn’t just running away from adulthood. He seeks to transcend a materially obsessed culture.

Salinger didn’t set out to write an anti-American diatribe, as The Catcher in the Rye has been labeled by those attempting to ban it. He was actually writing within the most American of literary forms, the jeremiad, to convey a message of reform. The jeremiad is a rhetorical method that was named for the prophet Jeremiah and used by the Puritans, one designed to keep American society in line with its ideals by calling attention to its flaws.[11]

An essential fact about The Catcher in the Rye, is that Holden does not reject historically American values. What he does is criticize the flawed way they’re enacted in modern society, and berate the replacement of morality with conformity.[12] As his sister Phoebe points out to him, Holden has the Robert Burns line of poetry wrong, an incorrect recollection that gives us the novel’s title: it’s “if a body meet a body,” rather than “if a body catch a body.” What Holden’s misremembering tells us is that he’s not “looking for love in all the wrong places,” but as with all “Jeremiahs” (and maybe a few bullfrogs), he wants to save society from a corrupt and deteriorating culture.[13]

_______

It’s about more than teen-age angst.

On its face, The Catcher in the Rye is about an immature teenage boy unable to come to terms with his impending adulthood. And more often than not, it is this perspective that’s taught in schools. Sure, high school students can relate to that narrative. But “life is hard, and Holden needs to get himself together,” is a cursory reading of the novel at best.

The book has also been described as “a story about a boy whose little brother has died,” with Holden’s negative perspective on the world seen as a manifestation of his grief.[14] This interpretation does indeed delve beneath the surface narrative. And it is enlightening. But there’s still more to Catcher than the psychology behind Holden’s actions.

Others have read Salinger’s work through the lens of his World War II-induced Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. But, what’s the point of writing that book? For therapeutic purposes, perhaps? Holden’s exchange with Mr. Antolini suggests such a possibility, that he may be able to help himself by helping others with his novel. It is true that we are all “broken” in one way or another, and Catcher is most certainly relatable on that level. But, the self-imposed exile Salinger is so famous for suggests a purpose other than reaching out to other “irreparably damaged” people with a healing message.[15]

I would argue that The Catcher in the Rye is a re-fashioned jeremiad. Not only because this interpretation considers the author and his historical context, but because, as Lionel Trilling points out, “literary situations [are] cultural situations.”[16] Understanding Salinger’s work as a jeremiad takes “the animus of the author” into account.[17] That is, what he wants to see happen as a result of people reading his book.

_________

What the heck is a Jeremiad?

Considered America’s first distinct literary genre, the jeremiad is a political sermon that, as mentioned above, takes its tone from the biblical prophet Jeremiah. It’s a mode of public exhortation used by the New England Puritans through the close of the eighteenth century for the purpose of social revitalization. In other words, the American jeremiad is a call for America to self-correct.[18]

These days, in industrialized societies like ours, it’s genres such as film, popular music, and literature that serve to expose injustices, inefficiencies, and immoralities in social structures. These modes influence culture by getting us to think about the shortcomings in our society. This leads to new insights, which in turn take root and reshape cultural expectations.[19]

_________

There’s a long history of literature as jeremiad.

Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye belongs to a lineage of American writers who have inherited and re-fashioned the jeremiad genre, authors who produced literature thick with spiritual protest.[20] Harriett Beecher Stowe’s abolitionist novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, for example, lambastes the country’s great sin of slavery, (and resulted in active resistance to the Fugitive Slave Act).[21] Henry David Thoreau’s essay Life Without Principle decries America’s narrow focus on making money, as well as the superficial nature of media, that “blunt[s]” a person’s sense of what is right.[22] Then there’s John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath, which laments the widespread foreclosures and subsequent homelessness caused by the “double whammy” of the Depression and the Dust Bowl. This work takes aim at “American greed, waste, and spongy morality.[23] And the lineage continues right up through Salinger and beyond.

Given Holden Caulfield’s constant judgement of the world as he sees it, The Catcher in the Rye is nothing if not the “catalogue of iniquities” inherent to the jeremiad form.[24] Interestingly, the fact that Catcher’s critique of mainstream American goals has led to it being labeled “un-American” parallels the history of the American jeremiad itself.[25]

The Puritans failed to realize how their self-denunciations would sound to non-New England ears. And they were nothing short of shocked when others took their jeremiads at face value, which prompted leaders from competing charters to proclaim New England “a sink of iniquity.”[26] Bearing this in mind, it became necessary to explain that the jeremiad was a rhetorical exercise, intended as motivation to live up to American ideals.

A similar reproach is echoed in Sinclair Lewis’ declaration, “I love America… I love it, but I don’t like it,” a sentiment that also runs through the following passage from The Catcher in the Rye[27]:

But you’re wrong about that hating business. I mean about hating football players and all. You really are. I don’t hate too many guys. What I may do, I may hate them for a little while, like this guy Stradlater I knew at Pencey, and this other boy, Robert Ackley. I hated them once in a while – I admit it – but it doesn’t last too long, is what I mean. After a while, if I didn’t see them, if they didn’t come in the room, or if I didn’t see them in the dining room for a couple of meals, I sort of missed them. I mean I sort of missed them.[28]

Though Holden does indeed lambaste his classmates, as this passage shows he doesn’t carry any ongoing animosity toward them, or football players generally. Rather, his indictments call out particular behaviors commonplace in the larger society.

_________

What makes Holden Caulfield a “Jeremiah”?

Holden expresses a fear that he’s disappearing as he crosses from one side of the road or street to the other, an image that bookends the narrative. This symbolizes his sense of diminishing authenticity within American society. As Perry Miller argues in his work on the American jeremiad, since the days of Jonathan Edwards (a fiery eighteenth-century minister referred to as the last Puritan), western civilization has put reflections about the larger meaning of existence aside.[29] We have distracted ourselves with materialism and concerns for image, pursuits that do nothing to address the ills of society. And it is this demise of American ideals that Allie Caulfield’s death signifies, an interpretation underscored by Holden’s prophetic appeal, “Allie, don’t let me disappear,” when crossing the street toward the end of the novel.[30]

And, Holden Caulfield’s iconic red hunting hat is the most important symbol in The Catcher in the Rye. It alludes to the “hunters” mentioned in the book of Jeremiah, invading nations invoked as divine retribution for Israel’s failure to heed the prophet’s warnings.[31] The hat’s color is significant because red is the traditional color of forewarning, or signaling alarm. Fire trucks and ambulance lights both flash red, as do those at railroad crossings. In keeping with what the hat symbolizes, Holden’s reference to it as a “people hunting hat” indicates that he is “taking aim” as it were, to expose their hypocrisy and “phoniness.” To read it as a call for actual violence is a failure to engage the novel’s symbolic language. Needless to say, no one escapes Holden’s critical eye.

_________

What are Holden’s Puritanical ideals?

Though the fervor of Holden’s accusations is typically attributed to him being a “disaffected teen,” his targets align with themes common in the colonial pulpit, specifically, being tempted by profits and pleasures, false dealing with God, and the corruption of children.[32]

Regarding profits, Holden makes it very clear that he considers his older brother to have sold-out. D. B. used to write short stories, including Holden’s favorite about a boy so proud of buying a goldfish with his own money, that he wouldn’t let anyone else see it. But now, D. B.’s a Hollywood screenwriter who buys extravagant cars for all to see. These days, it’s more about greed and image than writing good stories.[33]

The Christmas pageant at Radio City also takes a hit. The holiday has been reduced to nothing more than a means of chasing profit. Angels emerge from gift-wrapped boxes, and “guys carrying crucifies and stuff all over the place,” all while singing Oh, Come All Ye Faithful. In typical irreverent fashion, Holden calls out the crass commercialization of a subject that should be approached with reverence and respect, proclaiming “Jesus probably would’ve puked if He could see it—all those fancy costumes and all.”[34]

Holden specifically addresses false dealing with God in a story revolving around Ossenburger, a Pencey donor speaking at a school event. Ossenburger is an alumnus who “made a pot of dough in the undertaking business” with a nation-wide franchise of cut-rate funeral parlors, sufficient wealth to bankroll the dormitories commemorated with his name. During school chapel, Ossenburger urges students to talk to Jesus all the time, which he himself does (or so he says), even while driving his Cadillac. Holden’s remark about Ossenburger “shifting into first gear and asking Jesus to send him a few more stiffs,” targets hypocritical relationships with God, those based on show rather than piety and service.[35]

And where pleasures are concerned, unlike his “unscrupulous” classmate Stadlater who doesn’t even remember his dates’ names correctly, Holden aspires to spend time with girls he can relate to on an emotional or intellectual level. [36] Preferring a well-rounded relationship, Holden states, “If you really don’t like a girl, you shouldn’t horse around with her at all.”[37]

The corruption of children is a particular hotspot for Holden Caulfield. Discovering obscene graffiti on the wall of his sister’s grade school drives him “damn near crazy.” He is irate thinking about how “some dirty kid” would tell Phoebe and her classmates what the offensive phrase means. And how, given their young age, the act portrayed would be confusing and nothing less than disturbing.[38]

The very name of Salinger’s book refers to Holden’s need to protect “little kids.” But how so, what does the title of The Catcher in the Rye mean? In the context of the titular metaphor, he envisions himself patrolling a field of rye, and catching the children who are playing there should they start to go over the “crazy cliff,” typically understood as adulthood.[39] From Holden’s prophetic view, adulthood would require the corruption of these children to be in line with a degraded society, consumed with image and material goals rather than traditional American ideals.

_________

The Jeremiad: Not just an

“Undying Monotonous Wail.”[40]

Despite its catalogue of iniquities, the American jeremiad’s distinctiveness doesn’t lie in the intensity of its complaint, but precisely the opposite. At the heart of this genre is an unwavering optimism in the American ideal. Which, as scholar Sacvan Bercovitch maintains, grows more emphatic “from one generation to the next.”[41]

Which is why Phoebe Caulfield enters the picture when she does. She embodies the “next” generation Bercovitch is referring to. The fact that Phoebe is the only character throughout the novel who actually listens to what Holden has to say is significant, in that she’s the one who “hears” his prophetic message.[42] And Holden allows her to wear his hunting hat, which establishes Phoebe as successor to Holden’s mission. Finally, Holden literally sets Phoebe in motion with a ticket for the carousel, where she optimistically sets her sights on the golden ring, an obvious symbol for the American ideal. The proverbial torch has been passed, with Phoebe carrying Holden’s mission forward.

_________

In Conclusion.

Reading The Catcher in the Rye as a re-fashioned jeremiad, we understand that Salinger’s intent was not to malign America. Very far from it. Like the Puritan jeremiads whose message was also misunderstood, Catcher urges America to remember the ideals on which it was founded, principles we appear to have forgotten, and to self-correct. What Salinger hoped to accomplish is that the readers of his novel would make that happen. But like the question of whether or not Holden will apply himself in school next year, it’s up to us to engage the endeavor.

That’s my take on J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye – what’s yours?

Check out this Discussion Guide to get you started.

#post-war social commentary #banned #Puritan #published 1950s

Endnotes:

[1] Quindlen, Anna. “Public & Private; Dirty Pictures.” The New York Times. April 22, 1990.

[2] Whitfield, Stephen J. “Cherished and Cursed: Toward a Social History of the Catcher in the Rye.” The New England Quarterly, Vol. 70, No. 4 (Dec., 1997), 575.

[3] Steinle, Pamela Hunt. In Cold Fear: The Catcher in the Rye Censorship Controversies and Postwar American Character. (Columbus: Ohio State University, 2002), 73, 52.

[4] Steinle, 61.

[5] Mydans, Seth. “In a Small Town, a Battle Over a Book.” The New York Times, (Sept. 3, 1989).

[6] Whitfield, 575.

[7] Laser, Marvin and Fruman, Norman. “Not Suitable for Temple City.” in Studies in J. D. Salinger: Reviews, Essays, and Critiques of The Catcher in the Rye, and other Fiction. Edited by Marvin Laser and Norman Fruman. (New York: The Odyssey Press, 1963), 127.

[8] Mydans.

[9] Mydans.

[10] Shields, David and Salerno, Shane. Salinger. (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2013), 265.

[11] Bercovitch, Sacvan. The American Jeremiad. (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2012), xli; Miller, Perry. Errand Into the Wilderness. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1984), 10.

[12] Steinle, Pamela. “If a Body Catch a Body: The Catcher in the Rye Censorship Debate as Expression of Nuclear Culture.” Popular Culture and Political Change in Modern America. Contemporary Literary Criticism. Vol. 138, 2001.

[13] Mallette, Wanda; Morrison, Bob; Ryan, Patti. “Lookin’ for Love.” Urban Cowboy Soundtrack. (Hollywood: Full Moon, 1980); Shields and Salerno, 265.

[14] Menard, Louis. “Holden at Fifty: The Catcher in the Rye and what it spawned.” The New Yorker. (September 24, 2001).

[15] Shields and Salerno, 243.

[16] Trilling, Lionel. “On the Teaching of Modern Literature.” First published as “On the Modern Element in Modern Literature.” Partisan Review, January-February 1961.

[17] Trilling.

[18] Bercovitch, Sacvan. The American Jeremiad. (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2012), xli; Miller, Perry. Errand Into the Wilderness. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1984), 10.

[19] Turner, Victor. From Ritual to Theatre: The Human Seriousness of Play. (New York: Performing Arts Journal Publications, 1982), 40-45; Turner, Victor. “Liminal to Liminoid, in Play, Flow, and Ritual: An Essay in Comparative Symbology.” Rice Institute Pamphlet – Rice University Studies, 60, no. 3 (1974), 71.

[20] Bercovitch, Sacvan. The Rites of Assent: Transformations in the symbolic Construction of America. (New York: Routledge, 1993), 18.

[21] Senior, Nassau William. American Slavery: A Reprint of an Article on “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” (London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans & Roberts, 1856), 2.

[22] Thoreau, Henry David. Life Without Principle. (London: The Simple Life Press, 1905), 29.

[23] Shillinglaw, Susan. “John Steinbeck, American Writer.” The Steinbeck Institute.

[24] Tolchin, Karen R. Part Blood, Part Ketchup: Coming of Age in American Literature and Film. (New York: Lexington Books, 2007), 38; Bercovitch (2012), 6-7.

[25] Laser, Marvin and Fruman, Norman. “Not Suitable for Temple City.” in Studies in J. D. Salinger: Reviews, Essays, and Critiques of The Cather in the Rye, and other Fiction. Edited by Marvin Laser and Norman Fruman. (New York: The Odyssey Press, 1963), 127.

[26] Miller, Perry. The New England Mind: From Colony to Province. (London: The Belknap Press, 1981), 173-174.

[27] Miller, Perry. “The Incorruptible Sinclair Lewis.” The Responsibility of Mind in a civilization of machines. Edited by John Crowell and Stanford J. Searl, Jr. (Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press, 1979), 121.

[28] Salinger, J.D. The Catcher in the Rye. (New York: Little Brown and Co., 1991), 187.

[29] Rowe, Joyce. “Holden Caulfield and American Protest.” In New Essays on The Catcher in the Rye. Edited by Jack Salzman. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 88; Van Engen, Abram C. City on a Hill. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020), 248; Brand, David C. Profile of the Last Puritan: Jonathan Edwards, Self-love, and the Dawn of the Beatific. (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1991).

[30] Salinger, 198.

[31] Ellicott’s Commentary for English Readers. https://biblehub.com/commentaries/jeremiah/16-16.htm; The New Oxford Annotated Bible. Edited by Michael D. Coogen. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), Jeremiah 3:12-23, Jeremiah 27, Jeremiah 6:13.

[32] Tolchin, 41; Bercovitch (2012), 4.

[33] Salinger, 16.

[34] Salinger, 137.

[35] Salinger, 16.

[36] Salinger, 31.

[37] Salinger, 62.

[38] Salinger, 201.

[39] Salinger, 173.

[40] Bercovitch (2012), 5.

[41] Bercovitch (2012), 6.

[42] Moore, Robert P. “The World of Holden.” The English Journal. Vol. 54, No. 3 (March 1965), 160.

Images:

.

1 The Catcher in the Rye cover from the 1985 Bantam edition. Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Catcher-in-the-rye-red-cover.jpg Cropped by User.

2 Rembrandt van Rijn. Jeremiah Lamenting the Destruction of Jerusalem. 1630. Public Domain via Rijkjsmuseum.nl/nl http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.5242

3 Cotton Mather. By Peter Pelham, artist – http://www.columbia.edu/itc/law/witt/images/lect3/, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=80525

4 Holden Caulfield’s red hunting hat. Clipartmax.com https://www.clipartmax.com/png/middle/121-1213961_the-red-hunging-hat-2-discussion-posts-kate-said-red-hunting-hat.png (The original image has been flopped.)

5 First-edition cover of The Catcher in the Rye (1951). Public Domain. Source, Nate D. Sanders auctions (direct link to jpg) via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Catcher_in_the_Rye_

(1951,_first_edition_cover).jpg

Original image retouched by uploader, and cropped by current user.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!