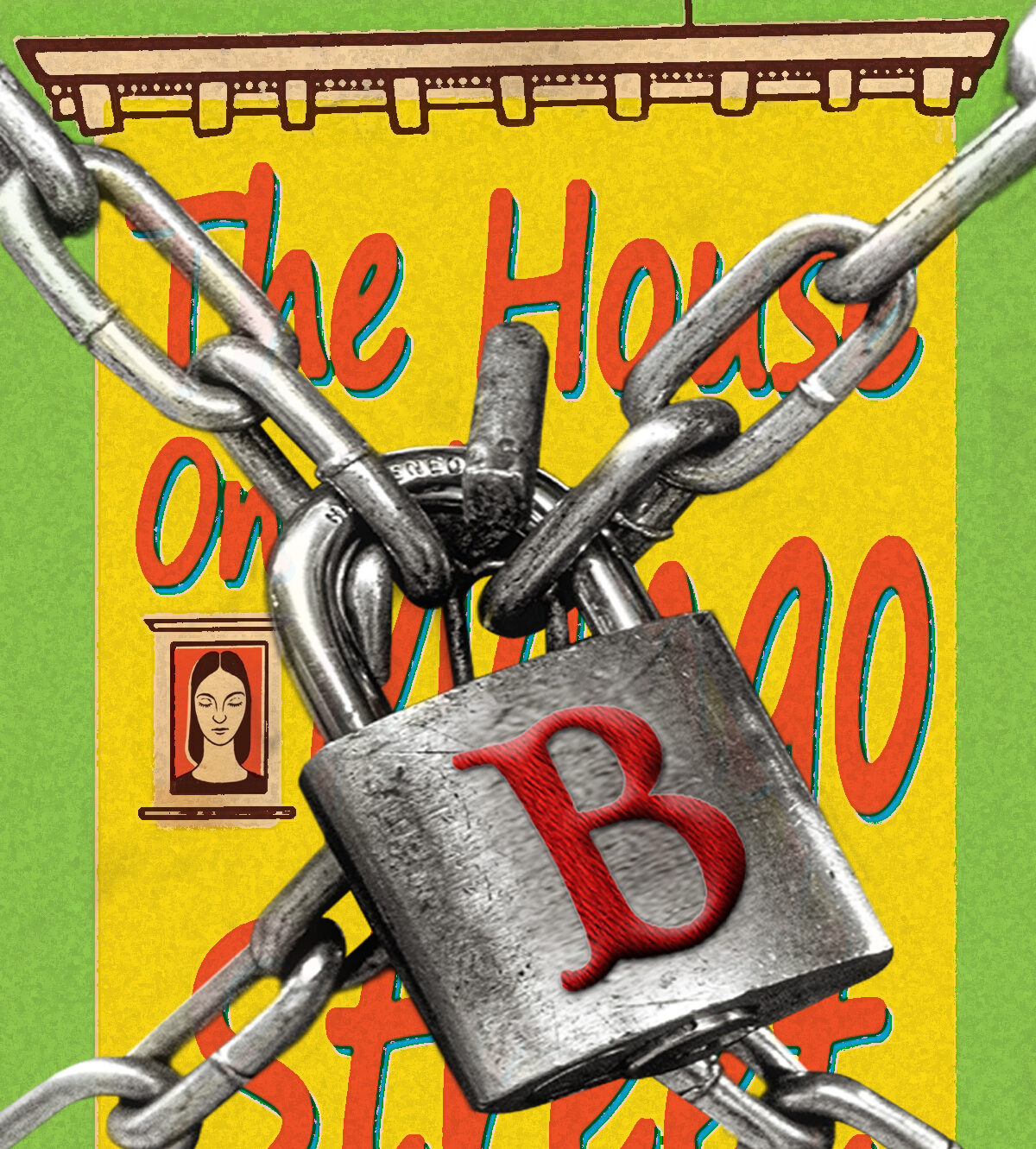

The House on Mango Street: A bridge of unity.

B

B

anned due to the social issues it addresses, The House on Mango Street tells the culturally significant story of Esperanza as she comes of age in the Hispanic quarter of Chicago.

Cisneros’ work was also among a number of books involved in a censorship suit revolving around a 2010 Arizona law specifically designed to ban a Mexican American studies program being taught in the Tucson Unified School District. For details about the movement sparked by this turn of events, take a look at Book Bans: a case study in how to push back.

These days book banners have broadened their scope to overwhelmingly target the entire BIPOC community: black, indigenous, people of color. (As well as LGBTQ+ individuals, but that’s another post – check it out here.)[1] The reason typically cited for this diversity-squashing move is concern for the social issues presented in these books.

This state of affairs is nothing less than tragic. When we are blind to the issues communities are grappling with, and denied the opportunity to explore diverse ideas, the potential for understanding and engagement within our communities goes out the window. On this note, Sandra Cisneros outlines what she sees as her responsibility as an author:

.

I have suspected for a long time now that our job as Chicanos, as Mexico-americanos, as amphibians, as citizens with one foot over there and one over here, is to be the bridge of unity…[2]

During her studies at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, Cisneros became aware that the language of working-class Mexican Americans was “nowhere to be found” in American literature.[3] She came to realize that her community had never been portrayed “with love and honesty.”[4] That’s when she found her voice and set out to do just that, and in doing so establish that bridge of unity:

.

[In my work,] I hope that people see their story being written about, and it gives them new options and possibilities to imagine something outside of what television or what the school counselor could imagine for them. I get lots of letters from all kinds of people. There are some people most unlike me, maybe a white male, who’s riding the subway and said he read my book and it made him look at people on the subway across from him in a different way, in a more human way. I really hope it will humanize [us] to be more compassionate, to recognize ourselves. If you can recognize yourself in the person most unlike you in literature, then the book will have done its work.[5]

It would be easy to see The House on Mango Street as a memoir disguised as a novel, but Cisneros’ work isn’t her story alone. After graduating from the University of Iowa, she worked as a teacher, and as a counselor to high-school dropouts. The vignettes that comprise Mango Street incorporate characters based on the lives of her students. And, it’s these women Cisneros refers to in the book’s simple dedication “To the Women.” [6] So, Mango Street is indeed the portrayal of a community rather than one individual’s experience.

The House on Mango Street most certainly accomplishes Cisneros’ mission… to promote understanding and compassion between people with differing backgrounds and cultures. Which, in turn, opens the proverbial door to engagement within our communities.

Mango Street’s House Symbolism

The house symbolism at the heart of The House on Mango Street functions on several levels. Most broadly, Cisneros’ work is often described as a bildungsroman, a formative novel about the psychological and moral growth of a protagonist. As you might have guessed, this literary genre originated in Germany. In the German language, bildung means education, and roman means novel. Therefore, a bildungsroman is a novel of education or formation.[7]

What does this have to do with houses? The house is a common symbol for the psyche, which according to Carl Jung, represents one’s current “state of consciousness, with hitherto unconscious additions.”[8] In other words, a place you presently inhabit that has room(s) for growth. And it’s interesting to note that Esperanza writes about her house before she tells the reader about her name.

As Cisneros indicates, her protagonist Esperanza is “in that nebulous age between childhood and adulthood,” developing into an adult by fits and starts.[9] And, Mango Street does indeed function on a pattern of growth where a young person encounters the outside world, examines it in relationship to themselves, and forges an identity that incorporates those experiences. Symbolically speaking, those experiences are the contents filling a new room in their psyche.

Cisneros’ narrative explores the cultural forces that shape identity. Her adaptation of the bildungsroman charts Esperanza’s developing sexual and social consciousness as she grows up in her Mexican father’s house, located in the Humboldt Park neighborhood of Chicago.[10]

In an early section of Mango Street called “My Name,” Esperanza says she’d like to baptize herself under a new name – ZeeZee the X. As observed by English professor Martha Satz, this name suggests a variable to be expressed, indicating an identity to be shaped. And by the end of the work, we learn what that variable is – Cisneros’ protagonist is a Chicana writer, one who has rejected the traditional Chicano definition of a woman’s role and status.[11]

House Imagery and the American Dream

House imagery is also linked to the American Dream, in that home ownership has long been considered one of its core components. Owning a home has clear economic advantages, such as tax benefits, accumulating wealth by accessing credit, and building equity.

For immigrants, ties to the American Dream can run even deeper, when owning a house is about putting down roots, establishing a home. And it’s often associated with regaining the self-identity that was lost when they left their homes behind to emigrate to the U.S.[12]

Cisneros invokes this tie to the American Dream in Mango Street’s opening pages. Esperanza’s parents frequently tell their children that one day they would have a house that would be theirs “for always so [they] wouldn’t have to move each year.”[13]

And the house they imagined would also signify success in their new country. Their house would have stairs “like the houses on T.V.” It would be “white with trees around it,” and have “a great big yard.”[14] In other words, it would be just like the houses the families portrayed in television shows like Leave it to Beaver, Father Knows Best, and The Brady Bunch live in. This is the house Esperanza’s mother dreamed of in the stories she told her children before they went to bed, one that represents both home and American success.

A House Can Also Be a Prison

The house on Mango Street didn’t compare with the T.V. houses by any stretch of the imagination. For starters, it was in an impoverished neighborhood. And, unlike the houses on television, it was small and red. There was no front yard, its windows were tiny, bricks were crumbling in places, and the front door would swell to the point of being difficult to open.

Cisneros has described the house that inspired the one on Mango Street as a prison, one that was grounded in class discrimination, doing damage to her self-identity.

.

I used to be ashamed to take anyone into that room, to my house, because if they saw that house they would equate the house with me and my value. And I know that house didn’t define me; they just saw the outside. They couldn’t see what was inside.[15]

Cisneros’ treatment of this state of mind appears in an exchange between Esperanza and a nun who teaches at her school – one that occurs after school hours as Esperanza was playing in front of where her family lives. The nun’s reaction to seeing where Esperanza lives is “You live there?”

.

The way she said it made me feel like nothing. There. I lived there. I nodded. [16]

In that moment, Esperanza knew she had to have a house she could point to without feeling judged and ashamed – and the house on Mango Street isn’t it. Though Esperanza’s parents insist the situation is temporary, this house still feels like the prison Cisneros described… being seen as of lesser value simply because of where she lived.

Esperanza also expresses a wish for a house of her own. Not a “home in the heart” like Elenita the bruja, “witch woman,” foretells for her, but a house.[17] And when Esperanza owns her own house:

.

I won’t forget who I am or where I came from. Passing bums will ask, Can I come in? I’ll offer them the attic, ask them to stay, because I know how it is to be without a house.[18]

For Esperanza, a house of her own not only means she has overcome the poverty she grew up around, but also the patriarchal Mexican culture she pushes back against – a culture that considers “becom[ing] someone’s wife” as the only destiny for a daughter. [19]

For the women in several of Mango Street’s vignettes, the houses they live in become prisons, because their possessive fathers and/or husbands confine them there.

What Esperanza strives for is:

.

Not a flat. Not an apartment in back. Not a man’s house. Not a daddy’s. A house all my own. With my porch and my pillow, my pretty purple petunias. My books and my stories. My two shoes waiting beside the bed. Nobody to shake a stick at. Nobody’s garbage to pick up after.

Only a house quiet as snow, a space for myself to go, clean as paper before the poem.[20]

Unlike the house on Mango Street, Esperanza’s house clearly represents the freedom to cultivate a healthy self-identity, one not diminished by poverty, or tethered to a husband or father.

Cisneros as Storyteller

As mentioned above, Sandra Cisneros set out to fill a literary gap by portraying her community with love and honesty. And, the very structure of her narrative reflects an essential experience among Mexican families, both in Mexico as well as immigrant Mexican families in the U.S. – the oral tradition of storytelling.[21]

Cisneros specifies that “it wasn’t a naïve thing, it wasn’t an accident”:

.

I wanted to write a series of stories that you could open up at any point. You didn’t have to know before or after and you would understand each story like a little pearl, or you could look at the whole thing like a necklace. That’s what I always knew from the day that I wrote the first one… I didn’t know the order they were going to come in, but I wasn’t trying to write a linear novel.[22]

The House on Mango Street has 44 “chapters,” if you will. And each vignette relates a particular story, one that not only stands on its own but is chockful of cultural information. When taken as a whole, this collection of anecdotes paints a cultural picture as rich as any family history handed down by grandma.

Even as a graduate student at the University of Iowa, Cisneros was interested in voices and loved listening to people, noting that she’s more concerned with the how than the what of what they have to say. In fact, she considers her deep appreciation for the rhythm of the spoken word to be her “original love.”[23]

As Latino author Isaac Mizrahi points out, Latin-American cultures have a meandering, inverted pyramid communication style. That is, giving context and supplying all the relevant facts of the story before ultimately making your point. This is the opposite of most Anglo cultures, which tend to stress leading with the main idea, then “fleshing it out” with details.[24]

The tales in Mango Street’s vignettes are related in just such a meandering manner. Take Cathy Queen of Cats, for example. Esperanza tells us all about Cathy… where she lives, who she lives next door to, that two girls, Benny and Blanca who are raggedy as rats, live across the street. We hear how Edna’s brother cheated her out the family’s building. We hear about everyone on Cathy’s block. Then we hear about Cathy’s cats. And finally, Esperanza makes her point and tells us that Cathy’s family will “just have to move a little farther north from Mango Street, a little farther away every time people like us keep moving in.”[25]

We see the same pattern in the Meme Ortiz segment. Esperanza tells us all about Meme’s dog, its breed, how big it is, the color of its eyes, and even how it runs. Then, we hear about the house Meme moves into… that Cathy’s father built it, that the stairs are crooked, that the yard is mostly dirt. And, Esperanza informs us that balls get stuck in the neighborhood’s gutters. Only in the last two lines do we hear about the titular character, that he won the friends’ First Annual Tarzan Jumping Contest… but broke both arms doing it.[26]

In The First Job, Esperanza relates how she was going to start looking for a job “the week after next.” She tells us how when she came home that afternoon, she was all wet because Tito pushed her into the open water hydrant. We find out that her mother called Esperanza into the kitchen before she even had a chance to go and change, and that her Aunt Layla was sitting in the kitchen drinking coffee with a spoon.

Then, we hear every little detail about how and why she gets this job, and what the job entails. But once again, Esperanza only reveals the unsettling point of the story in the last couple of lines. An older man who she assumes also works there manipulates her into giving him “a birthday kiss.” But, just as she was about to peck him on the cheek, “he grabs my face with both hands and kisses me hard on the mouth and doesn’t let go.”[27]

Cisneros’ meandering style walks us, leisurely and blithely, right up to the powerful point she makes in each vignette. And this rhythm makes the experiences she ultimately relates about her community all the more potent.

The Peculiar Flavor of Cisneros’ English

She may use very little Spanish in Mango Street, but it’s what gives Cisneros’ English what she describes as “its peculiar flavour.”[28] “The sensibility,” as Cisneros points out, “the diminutives” of the very tender, “that’s Spanish.”[29]

We see this linguistic marker sprinkled throughout Mango Street. For example, while cloud gazing one day, Esperanza’s sister Nenny gives names to the smaller clouds in the formation they’re admiring, calling them “little Joey, Marco, Nereida and Sue.”[30]

The older children in the wild and troublesome Vargas family are simply called by their given names. But in her tale of how he chipped his tooth on a parking meter, Esperanza refers to the youngest Vargas as “little Efren.”[31]

Diminutive language also appears in the vignette about Sire (who papa says is a punk and Mama says she shouldn’t talk to) and his infantilized girlfriend Lois (who is “tiny and pretty and smells like baby’s skin”). Esperanza notices Lois’ bare feet as they stand next to each other in Mr. Benny’s grocery, and compares her “barefoot baby toenails” to “little” pink seashells.[32] In this case, the diminutive’s linguistic association with the “little” pink seashells of Lois’ toenails serves to underscores her infantilized nature.

Cisneros notes that “looking at inanimate objects as if they were animate” also reflects the Spanish language.[33] And, Mango Street is peppered with this delightful linguistic device. For instance, “our house with its feet tucked under like a cat.”[34] As well as “the shoes talk back to you with every step.”[35] Then there’s “the little wooden door that has wedged shut the dark for long opens with a sigh and lets out a breath of mold and dampness.”[36]

The peculiar flavor of Cisneros’ English not only gives her work a captivating, easy to read rhythm, it gives us insight into the Mexica-American culture Mango Street portrays.

Refusing to Wait For the Ball and Chain

The House on Mango Street opens with Esperanza revealing that she has the same name as her great-grandmother. While Mango Street makes it clear that Esperanza is proud of her Mexican heritage, like a lot of young people straddling two cultures, she rebels against some of its traditions. In Esperanza’s case, those having to do with the patriarchal aspects of the culture that Cisneros mentions on the opening page.

Esperanza tells how boys and girls “live in separate worlds. The boys in their universe and we in ours.”[37] Her brothers, for example, have plenty to say to Esperanza and her sister inside the house. But when they’re outside “they can’t be seen talking to girls.”[38]

We learn pretty quick that Esperanza is a spunky girl who has plans for her life. She may share a name with her great-grandmother, but she has no intention of being subdued like this once “wild horse of a woman” had been, who like so many other women ended up looking out the window their whole lives,” “sit[ting] their sadness on an elbow.”[39]

Several of Cisneros’ vignettes revolve around women who find themselves in similar circumstances. There’s Alicia, whose father insists she forego her studies at the university. Because, her mother has died, and as a woman, it is now Alicia’s place to fulfill the never-ending task of taking care of the family.[40]

Rafaela wishes she had hair like Rapunzel, the fairy tale character who is locked in a tower. Rafaela’s husband plays dominoes on Tuesday nights. And he locks her indoors like Rapunzel while he’s away. Rafaela spends her time wishing she could follow the music from the dance hall down the street, to “go there and dance before she gets old.” [41]

And there’s Sally, who’s not much older than Esperanza but is already married. Sally grew up with a father who says “to be beautiful is trouble,” and beat her because he was afraid she was going to run away and shame the family like his sisters did.[42] Sally claims she’s in love, but Esperanza thinks she married early to escape her father.

Sally says she likes being married because she can buy her own things when her husband gives her money. But, he doesn’t like her friends so they aren’t allowed to visit. He won’t let her talk on the phone either. And, she sits at home because she’s afraid to leave the house without his permission.[43]

Esperanza is different from most of the women she tells us about. They’ve done what Esperanza has decided she will not do – grow up “tame” and lay her “neck on the threshold waiting for the ball and chain.”[44] She is “Simple. Sure. [She is] one who leaves the table like a man, without putting back the chair or picking up the plate.”[45]

Magnificent Mile Made Me Ashamed of My Shoes

In her essay, Notes of a Native Daughter, Cisnero cites a quote from a Chicagoan, one retold by writer Studs Terkel, “I always feel a chest-welling when I drive along the lake… Yet I know four blocks over is desperation.”[46]

That’s the kind of neighborhood Esperanza is growing up in. And her honest portrayal of those struggling to make a good life in this poverty-stricken environment is one of the social issues challengers of The House on Mango Street find objectionable.

Cisnero further notes that “Chicago’s Magnificent Mile made others feel magnificent but only made [her] ashamed of my shoes.”[47] Instances of Esperanza being ashamed of her shoes pop up periodically in Mango Street.

Given Cisneros’ remark, this suggests something other than a young girl wishing her mother had chosen a more fashionable style of footwear when buying clothes for her daughter. Esperanza’s embarrassment about her shoes clearly alludes to Cisneros’ reaction to the obvious disparity between downtown Chicago and her own neighborhood.

In Esperanza’s neighborhood, basic services are already sparce and diminishing even further. Trash pick-up, for example, was halved in Cisneros’ own neighborhood from twice a week to once, even though the population (and therefore trash) had doubled. This experience undoubtedly informs the observation Esperanza makes about how the people who live in houses like “the ones with gardens” where her Papa works “have nothing to do with last week’s garbage,” or fear of the rats that come with it.[48]

The vignette Geraldo No Last Name shows us a severely understaffed hospital, and the repercussions of such a situation. When a young man named Geraldo is the victim of a hit and run accident, there’s “nobody but an intern working all alone” in the emergency room.[49]

If there had been a surgeon, or if one had even shown up, maybe Geraldo wouldn’t have died. But there wasn’t a surgeon, or a fully trained doctor of any kind. So Geraldo bleeds to death, more the victim of inequitable resources than the hit and run driver who sent him to the hospital.

We’ve already touched upon the housing conditions in Esperanza’s neighborhood. The residents live in crumbling houses, or are jammed together in run-down flats with broken water pipes the landlord refuses to fix. And even those aren’t affordable. Family members, like grandpa in The Family of Little Feet, must sleep on the living room couch for lack of adequate space.[50]

Though it isn’t mentioned explicitly, the careful reader can see that food insecurity is also an issue. Rosa Vargas’ husband abandoned her, “without even leaving a dollar for bologna” to feed the large family he left behind.[51]

Minerva and her children are also food insecure. We learn that Minerva is always sad and has many troubles. In this vignette Esperanza describes Minerva’s nightly routine. So, the refence to feeding her children “their pancake dinner” indicates this isn’t a breakfast-for-dinner event for the fun of it. Rather, it’s the routine. Minerva’s kids have pancakes for dinner because that’s all she can afford.

And, when Esperanza talks her mother into letting her eat lunch at school, she takes “a rice sandwich because we don’t have lunch meat.”[52] The fact that this vignette is titled A Rice Sandwich tells the reader it’s more about what she has for lunch than it is about where she eats it. Especially since, in keeping with her meandering style, Cisneros caps the vignette with a description of the unpleasant sandwich Esperanza eats in the school canteen.

Esperanza doesn’t tell her family that the reason she doesn’t want to go on their Sunday drives through neighborhoods that have houses with gardens is because she’s ashamed. But she is – “all of us staring out the window like the hungry. I am tired of looking at what we can’t have.”[53] And as Esperanza’s mother wisely points out in the vignette A Smart Cookie, “Shame is a bad thing, you know. It keeps you down.”[54]

Poverty is an uncomfortable topic, to be sure. But banning books that address it does a disservice to every citizen of this country. It’s important to realize that everyone may not have it as good as we do. Stories like these not only show us how destructive poverty can be. Books like The House on Mango Street also help readers understand that overcoming poverty isn’t simply a matter of working harder or budgeting more wisely. And realizations like these are the first steps toward building that bridge of unity.

That is how it goes and goes.

Issues revolving around ethnicity addressed in The House on Mango Street clearly play a significant role in the work’s bannings. Especially these days when books exhibiting diversity are overwhelmingly challenged.

A perceived need to renounce diversity in the name of harmonious relations (as was the case in the dismantling of Tucson’s Mexican-American studies program) is not only dangerous, it’s an exercise in futility.

For, as author, activist and poet, Audre Lorde points out, it isn’t the actual differences between people that cause serious social division:

.

“It is rather our refusal to recognize those differences and examine the distortions which result from our misnaming them, and their effects upon human behavior and expectation.”[55]

One of the metaphoric functions of Esperanza’s name speaks to such misnaming. Esperanza tells us they say her name “funny” at school, “as if the syllables were made out of tin and hurt the roof of your mouth.” In its original Spanish, on the other hand, her name “is made out of a softer something, like silver. [56]

That her name is pronounced as if the syllables were made of tin when they say it rather than the silver it evokes in Spanish, indicates the ethnic dynamic. Esperanza’s Mexican heritage is clearly “less than” in this ethnic equation.

In the vignette Cathy Queen of Cats, the titular character Cathy, “great great grand cousin of the queen of France,” has something negative to say about pretty much everyone in the neighborhood.[57] And Cathy’s declaration to recent arrival Esperanza, that her family is moving because “the neighborhood is getting bad” makes the situation crystal clear. Embodying white flight, they’ll move “a little farther away every time people like [Esperanza] keep moving in.”[58]

Geraldo No Last Name is mentioned above in reference to lack of services in impoverished neighborhoods, but it’s also relevant here. Dialogue undoubtedly spoken by anglo police officers represents the discrimination that results from distorted differences. All these officers see is “just another brazer who didn’t speak English. Just another wetback. You know the kind.”[59]

It’s bad enough that Geraldo dies because the emergency room was severely understaffed. But, because of their distorted view of who he was, the police didn’t even consider the possibility that Geraldo was leading a meager existence so he could send money home to his family. And it didn’t seem to matter that someone would be worried about what happened to him.

Cisneros doesn’t just point the discriminatory finger at others. In Those Who Don’t she directs it at herself as well. [60] Their “knees go shakity-shake” and their “car windows get rolled up tight,” and their “eyes look straight” ahead when they go into “a neighborhood of another color” too.[61] “That is how it goes and goes.”[62] But it doesn’t have to.

Yes, it’s a lifetime pursuit to extract such distortions from our worldview, as we recognize, reclaim, and define the differences we’ve distorted. But we can work together with those we define as different from ourselves, as we endeavor toward a society where we can each flourish.

Chicago’s Barrio: Not a Colorful,

Sesame Street-like Neighborhood

Cisneros sees her male contemporaries’ characterization of life in the barrio as that of a “Sesame Street-like, funky neighborhood.”[63] “I’m sure [those colorful viewpoints] are true to some extent,” she states. But as a woman Cisneros wanted to counter those picturesque characterizations.[64]

Sexual assault is indeed one of the social issues Mango Street challengers contend they’re “protecting children” from hearing about.[65] But, assault doesn’t only happen in the barrio, and shielding teens from such content renders them naïve and vulnerable, like Lois (who symbolically smells like babies), the kind of girl who gets taken “into alleys.”[66]

In the vignette The Family of Little Feet, Esperanza and her friends are given high-heeled shoes that would otherwise have been thrown away. The girls realize these are grown-up lady shoes, but they have no idea that high heels are sexualized articles of clothing, or what that even means.

They innocently wear these shoes around the neighborhood, naively feeling grown and beautiful. After a while, the girls encounter a man sitting on the stoop of a tavern across the street from where they’re gathered. When he asks Esperanza’s friend Rachel her name, she tells him without thinking – and sets the following exchange in motion:

.

“Rachel, you are prettier than a yellow taxicab. You know that?”

But we don’t like it. “We got to go”, Lucy says.

“If I give you a dollar will you kiss me? How about a dollar. I give you a dollar,” and he looks in his pocket for wrinkled money.

“We have to go right now,” Lucy says taking Rachel’s hand because she looks like she’s thinking about that dollar.[67]

Though the girls come out of the encounter unscathed, it frightens them to the point that they hide the shoes “under a powerful bushel basket” on Rachel and Lucy’s back porch.[68] Rachel and Lucy’s mother ultimately finds the shoes and throws them away… and the girls are perfectly fine with that. It’s just a good thing Rachel was with someone who recognized the situation as dangerous.

We touched on the incident that occurs on the first day of Esperanza’s first job above, but in a different context. The conversation the older man initiates with Esperanza is predatory in nature, one that takes advantage of her clearly vulnerable state. He’s obviously done this before and knows exactly how to get Esperanza into a submissive and compliant state.

The outcome could have been much more physically devastating than a hard kiss on the mouth, but it’s still a violation, and as such psychologically damaging. Forewarned is forearmed, as the saying goes. And being familiar with this story could be the very thing that protects another young person from falling prey under similar circumstances… but they can’t be prepared if they aren’t allowed to read it.

It’s significant that The Monkey Garden and Red Clowns appear back-to-back. Over the course of their day in the “monkey garden” where the neighborhood kids hang out, a boy named Tito and his friends have gotten hold of Sally’s keys and refuse to give them back until she gives each one of them a kiss.[69]

As Esperanza watches Sally go into the garden with Tito’s buddies, her instincts are correct. She feels like something isn’t right, like Sally needed to be saved from Tito and his friends. So, Esperanza picks up “three big sticks and a brick and figure[s] this [is] enough.”[70]

When Esperanza confronts them, Sally tells her in no uncertain terms to go home. They all look at Esperanza “as if [she] is the one that is crazy,” making her feel ashamed for attempting to rescue her friend.

Sadly, it’s lack of information that leaves Esperanza vulnerable to the serious attack inflicted on her at the carnival in the following vignette. She’s waiting by the Tilt-a-whirl for Sally to return from an encounter with a boy she just met, whose friends stay behind with Esperanza. Though her assault isn’t described in detail, the reader is made aware that Esperanza has been raped.

The fact that Esperanza had no idea this act could be forced upon her makes matters even worse. The only information she has on the subject of sex came from movies, storybooks, and Sally (who previously shamed Esperanza for thinking she needed to be saved from a group of boys). As a result, Esperanza didn’t see being alone with this group of boys as the threat it was.

So, as Esperanza’s lamentation demonstrates, her assault is more than a matter of grievous physical violation, it’s also one of betrayal:

.

He said I love you, Spanish girl, I love you… Why did you leave me all alone? I waited my whole life. You’re a liar. They all lied. All the books and magazines, everything that told it wrong… Sally, you lied, you lied.[71]

Yes, sexual assault is another uncomfortable subject. And to be sure, conversations about personal violation or abuse of any kind should be handled in a careful and sensitive manner. Discussing a story where those things happen to a fictitious character is one way to do that. It’s a method social workers and counselors frequently utilize… in fact, with this very book.

Talking about something that happened to a fictious character allows students to gain the information they need to avoid situations like the one Esperanza found herself in without the trauma that can result from a more threatening “this can happen to you” version of such conversations.[72]

It’s understandable that some parents feel they should be the ones to having these conversations with their own children. But, prohibiting every student from reading a book because it mentions sexual assault isn’t protecting them at all. In fact, quite the opposite. It’s rendering them naïve, like Esperanza, and therefore vulnerable to falling prey themselves.

In Conclusion: Who’s going to make it better?

As they sit on Edna’s steps, Alicia is “listening to [Esperanza’s] sadness.” Esperanza is sorrowful because she lives in a house she’s ashamed of, in a place she doesn’t “ever want to come from.”[73] They talk about leaving Mango Street. And Esperanza declares she won’t come back “until somebody makes it better,” prompting Alicia to pose the question “who’s going to do it? The mayor?”[74]

Alicia has a point. It takes more than the mayor alone to make any place a better place to live. It takes all of us working together to accomplish that. And the first step is to recognize the humanity of people most unlike us, and cease seeing them in opposition to ourselves… to build a bridge of unity. Books like The House on Mango Street, that promote diversity and enlighten us to distorted perspectives, help us do that.

That’s my take on Sandra Cisneros’ The House on Mango Street – what’s yours?

Check out this Discussion Guide to get you started.

#banned books #Hispanic authors #published 1980s #The House on Mango Street

Endnotes:

[1] Kasey Meehan and Jonathan Friedman. “Banned in the USA: State Laws Supercharge Book Suppression in Schools.” PEN America.

[2] Jago, Carol. Sandra Cisneros in the Classroom: Do not forget to reach. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English, 2002. Pg 6.

[3] Gross, Rebecca. “Sandra Cisneros: Recognizing Ourselves.” American Artscape Magazine. Vol. No1, 2016. National Endowment for the Arts. https://www.arts.gov/stories/magazine/2016/1/telling-all-our-stories-arts-and-diversity/sandra-cisneros

[4] Gross, Rebecca. “Sandra Cisneros: Recognizing Ourselves.” American Artscape Magazine. Vol. No1, 2016. National Endowment for the Arts. https://www.arts.gov/stories/magazine/2016/1/telling-all-our-stories-arts-and-diversity/sandra-cisneros

[5] Gross, Rebecca. “Sandra Cisneros: Recognizing Ourselves.” American Artscape Magazine. Vol. No1, 2016. National Endowment for the Arts. https://www.arts.gov/stories/magazine/2016/1/telling-all-our-stories-arts-and-diversity/sandra-cisneros

[6] Queirós, Carlos J. “Sandra Cisneros: Facing Backward.” April 1, 2009. AARP. https://www.aarp.org/entertainment/books/info-04-2009/sandra_cisneros_house_on_mango_street_25th_anniversary.html

Sandra Cisneros Biography. Sandra Cisneros.com https://www.sandracisneros.com/mylifeandwork

[7] “What Is a Bildungsroman? Definition and Examples of Bildungsroman in Literature.” August 30, 2021. MasterClass

https://www.masterclass.com/articles/what-is-a-bildungsroman-definition-and-examples-of-bildungsroman-in-literature

[8] C. J. Jung. Memories, Dreams, Reflections. Edited by Anelia Jaffe’. Translated by Richard and Clara Winston. New York: Vintage Books, 1961. Pg 198.

[9] Satz, Martha. “Returning to One’s House: An Interview with Sandra Cisneros.” Southwest Review. Vol. 82, Issue 2. Spring 1997

[10] “Sandra Cisneros’s Real House, Like the One on Mango Street.” Literary Chicago. https://chicagoliteraryhof.org/literary_chicago_map/landmark/sandra-cisneross-real-house-like-the-one-on-mango-street

[11] Matchie, Thomas. “Literary Continuity in Sandra Cisneros’s The House on Mango Street.” The Midwest Quarterly. Autumn, 1995. Vol 37, issue 1.

O’Reilly Herrerra, Andrea. “’Chambers of Consciousness’: Sandra Cisneros and the Development of Self in the BIG House on Mango Street.” The Bucknell Review. Vol. 30. Issue 1. Jan 1995. Pg 202.

Satz, Martha. “Returning to One’s House: An Interview with Sandra Cisneros.” Southwest Review. Vol. 82, Issue 2. Spring 1997

[12] Robb, Brian H. “Homeownership And The American Dream.” September 28, 2021. Forbes.com https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesrealestatecouncil/2021/09/28/homeownership-and-the-american-dream/?sh=7e48a8c623b5

Chandrasekhar, Charu. “Can New Americans Achieve the American Dream? Promoting Homeownership in Immigrant Communities.” 39 Harv. C.R.-C.L. L. Rev. 169 (2004) https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/hcrcl39&div=9&id=&page=

Scott, Roxanne. “A Nation Engaged: For Immigrants, Is Homeownership The American Dream?” October 14, 2016. Louisville Public Media. https://www.lpm.org/nation-engaged-immigrants-homeownership-american-dream

[13] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 4.

[14] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 4.

[15] “Sandra Cisneros.” In Interviews with writers of the post-colonial world. Edited by Jussawala, F., & Dasenbrock, R. W. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1992.Pg. 302

[16] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 4-5.

[17] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 64.

Cisneros, Sandra. “The Author Responds to Your Letter.” In A House of My Own. New York: Penguin Random House, 2015. Pg 310.

[18] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 87.

[19] Cisneros, Sandra. “Only Daughter.” Latina: Women’s Voices From the Borderlands. Edited by Lillian Castillo-Speed. New York: Touchstone/Simon & Schuster, 1995.

[20] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 108

[21] Reese, Leslie. Storytelling in Mexican Homes: Connections Between Oral and Literacy Practices. National Library of Medicine. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23565052/

Chicana/o/x Family Storytelling – Oral Traditions & Cultural Identity. INSTITUTE OF CHICANA/O/X PSYCHOLOGY & COMMUNITY WELLNESS https://razapsychology.org/2023/02/05/chicana-o-x-family-storytelling-oral-traditions-cultural-identity/#:~:text=We%20know%20our%20elders%20who,and%20strengthen%20our%20cultural%20identity.

[22] “Sandra Cisneros.” In Interviews with writers of the post-colonial world. Edited by Jussawala, F., & Dasenbrock, R. W. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1992. Pp 292, 305.

[23] “Sandra Cisneros.” In Interviews with writers of the post-colonial world. Edited by Jussawala, F., & Dasenbrock, R. W. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1992. Pg 291.

[24] Mizrahi, Isaac. “Storytelling Is A Different Story For Each Culture.” Feb. 19, 2019. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/isaacmizrahi/2019/02/19/storytelling-is-a-different-story-for-each-culture/?sh=6e8c4db667ad

[25] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 13.

[26] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 22.

[27] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 55.

[28] Nogue’, Pilar Godayol. “Interviewing Sandra Cisneros: Living on the Frontera.” Lectora. Vol. 2, 1996. Pg 68.

[29] Nogue’, Pilar Godayol. “Interviewing Sandra Cisneros: Living on the Frontera.” Lectora. Vol. 2, 1996. Pg 68.

[30] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 36.

[31] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 30.

[32] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 73.

[33] Nogue’, Pilar Godayol. “Interviewing Sandra Cisneros: Living on the Frontera.” Lectora. Vol. 2, 1996. Pg 68.

[34] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 22.

[35] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 40.

[36] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 70.

[37] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 8.

[38] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 8.

[39] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 11.

[40] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 32.

[41] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 79.

[42] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 81.

[43] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 102.

[44] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 88.

[45] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 89.

[46] Cisneros, Sandra. “Notes of a Native Daughter.” In Tales of Two Americas: Stories of Inequality in a Divided Nation. Edited by John Freeman. New York: Penguin Books, 2017. Pg. 21.

[47] Cisneros, Sandra. “Notes of a Native Daughter.” In Tales of Two Americas: Stories of Inequality in a Divided Nation. Edited by John Freeman. New York: Penguin Books, 2017. Pg. 24.

[48] Cisneros, Sandra. “Notes of a Native Daughter.” In Tales of Two Americas: Stories of Inequality in a Divided Nation. Edited by John Freeman. New York: Penguin Books, 2017. Pg. 23.

Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 86.

[49] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 66.

[50] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 3, 49.

[51] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 29.

[52] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 45.

[53] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 86.

[54] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 91.

[55] Lorde, Audre. “Age, Race, Class and Sex: Women Redefining Difference.” In Sister Outsider. Trumansburg, N. Y.: Crossing Press, 1984. Pp 114-123.

[56] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Intro.

[57] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 12.

[58] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 13.

[59] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 66.

[60] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 28.

[61] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 28.

[62] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 28.

[63] Satz, Martha. “Returning to One’s House: An Interview with Sandra Cisneros.” Southwest Review. Vol. 82, Issue 2. Spring 1997. Pg 169.

[64] Satz, Martha. “Returning to One’s House: An Interview with Sandra Cisneros.” Southwest Review. Vol. 82, Issue 2. Spring 1997. Pg 169.

[65] Cavendish-Jones, Colin. “Why was The House on Mango Street banned?” Enotes.

[66] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 73.

[67] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 41-42.

[68] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 42.

[69] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 96.

[70] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 97.

[71] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 100.

[72] Cisneros, Sandra. “The Author Responds to Your Letter.” In A House of My Own. New York: Penguin Random House, 2015. Pg 309.

[73] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 106.

[74] Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. Pg 107.

Images:

The House on Mango Street mock cover. Bartling.

Esperanza’s dream house.

Photo by Scott Webb on Unsplash

Sandra Cisneros in the backyard of the home that was the inspiration for the house on Mango Street.

https://chicagoliteraryhof.org/literary_chicago_map/landmark/sandra-cisneross-real-house-like-the-one-on-mango-street

The Storyteller by Publio de Tommasi. Public Domain.

https://picryl.com/media/the-storyteller-unknown-date-by-publio-de-tommasi-709137

Refusing to wait for the ball and chain.

Photo by Daria Nepriakhina on Unsplash

Magnificent Mile made me ashamed of my shoes.

Dovydenas, Jonas. Along 26th St. between Kedzie and Pulaski, in the predominantly Mexican American Little Village neighborhood, Chicago, Illinois by Jonas Dovydenas. Chicago, Illinois 1977. https://www.loc.gov/item/afc1981004.172/.

That is how it goes and goes.

Photo by Markus Spiske on Unsplash

Chicago’s barrio is not a colorful, Sesame Street-like neighborhood.

Along 26th St. between Kedzie and Pulaski, in the predominantly Mexican American Little Village neighborhood, Chicago, Illinois by Jonas Dovydenas. Chicago, Illinois. 1977. https://www.loc.gov/item/afc1981004.b71993/.

Who’s going to make it better?

Photo by Wai Siew on Unsplash