G

G

reek tragedies were intended to promote public discussion about how their society could avoid the same tragic mistakes the play deals with. What societal plight is Steinbeck warning us about?

Maybe Steinbeck’s dog Toby knew Of Mice and Men would become one of the most challenged books when he “made confetti” of the first draft.[1] Probably not. But even Steinbeck jokingly wondered whether the setter pup “may have been acting critically.”[2]

And indeed, Of Mice and Men consistently winds up on banned book lists. But, why is Of Mice and Men banned? Like a lot of banned books, Of Mice and Men is frequently challenged for “profanity,” and “offensive language.”[3] It’s been banned for similar reasons somewhere in the United States for decades.

Challenges in the 1970s came from (among other places) Oil City, Pennsylvania; Syracuse, Indiana; and Grand Blanc, Michigan. In 1983, the chair of the Knoxville, Tennessee school board vowed to eradicate all “filthy books” from the local school system, beginning with Of Mice and Men.[4] An Iowa City, Iowa parent challenged the book in 1991 because she didn’t want her daughter to “talk like a migrant worker” when she finished school.[5] And, it was still among the top ten most challenged books in 2020.[6]

Bannings for vulgarity continue. But, why has Of Mice and Men become so controversial? More recent challenges to Steinbeck’s novella include “racist language.”[7] Contemporary objections also involve statements that are “defamatory” to women and the disabled.[8]

Set in California during the Great Depression, Of Mice and Men has also been challenged because it contains “morbid and depressing themes.”[9] A 2015 challenger found it “too ‘negative,’ and ‘dark,’” further stating that the work “is neither a quality story nor a page turner.”[10] Not surprisingly, I beg to differ.

As challenges for “negativity” and “depressing themes” suggest, some people clearly consider literature’s function to be serving up “vicarious ‘happy endings,’” to sugar coat the hard truths of real life.[11] The best writers and readers, however, understand that literature can also be strong medicine – bitter perhaps, but necessary to continued social and emotional health.[12] Needless to say, Of Mice and Men is a dose of this medicine.

“In every bit of honest writing in the world,” Steinbeck noted, “there is a base theme. Try to understand [people], if you understand each other you will be kind to each other.”[13] This sentiment not only underscores concepts addressed elsewhere on this site, more importantly it’s the polar opposite of the thinking behind concerted efforts to ban books that promote diversity.

Steinbeck described his “whole work drive” as being aimed at “making people understand each other.”[14] And, the understanding engendered by Steinbeck’s novella runs deep, which makes it a perfect example of how novels are like a layer cake. By that I mean it contains several levels of meaning and perspectives of interpretation.

Of Mice and Men addresses the human condition on the social/historical level, the mythological level, as well as through a psychological filter. In fact, Steinbeck’s book has so much to offer that this essay will be posted in three segments. Let’s dig into the first installment.

…

It’s a Regular Greek Tragedy.

It all begins with why Of Mice and Men is called Of Mice and Men. Steinbeck’s novella is named for a line in Robert Burns’ 1785 poem To a Mouse, On Turning Her Up In Her Nest With The Plough. The mouse in Burns’ poem embodies the all-too-often futile hope, and fruitless planning that earthly creatures put into the future. Like most Tragic figures, Burns’ mouse is a tangible expression of the fear and misery a being experiences when compelled to vie with forces incomprehensibly bigger than itself.[15]

But Mousie, thou art no thy-lane, But Mousie, thou art no thy-lane,

In proving foresight may be vain

The best laid schemes o’ Mice and Men

Gang aft agley,

An’ lea’e us nought but grief an’ pain,

For promis’d joy! (lines 36-41) |

But mouse-friend, you are not along

in proving foresight may be vain:

The best-laid schemes of Mice and Men

Go oft awry,

And leave us only grief and pain,

For promised joy! [16] |

…

Steinbeck signals from the outset of his novella that mice signify inevitable failure. George is described in mouse-like terms, as “small and quick, dark of face, with restless eyes and sharp, strong features.”[17] And Lennie keeps a dead mouse in his pocket. Lennie carries a mouse in his pocket because he loves to pet soft, furry things. But despite how much he cares for them (or perhaps because he cares so much), no matter how hard he tries Lennie just can’t control his incredible strength, and inevitably kills them by handling them too roughly.[18]

As noted above, one reason Of Mice and Men has “evoked controversy and censorious action” is because it’s “painful” to read.[19] And, I don’t mean that it’s difficult to understand. It hurts to read Of Mice and Men. And that’s because it’s a Tragedy, in the “classic Aristotelian/Shakespearean sense.”[20] Bearing that in mind, it’s very telling that Steinbeck wrote Of Mice and Men in an experimental form he called a “playable novel,” a novel that could be “played from the lines, or a play that could be read.”[21]

It isn’t only that the work’s form parallels that of Tragedy. Of Mice and Men is consistent with Tragedy’s emphasis on plot that revolve around conflicts between opposing if not irreconcilable impulses: mortals and gods for example, law and nature, or individuals and states. And, needless to say, tragedies never end well. The narrative typically culminates in the degradation or destruction of a key individual, coalition, or society.

Though early tragedies were often set in the mythic past, they were purposely (albeit indirectly) intended to promote public debate about current interests and the contemporary condition of the state. In short, for the Greeks tragedies were a form of public education. They were meant to horrify and admonish the citizenry. By shocking and unsettling the audience, tragedies forced discussions of what needed to happen in order to avoid such a fate. So, they weren’t advocating resignation, or conveying a fatalistic message. Tragedies were intended to serve as a warning, and function as a call to action.[22]

Consistent with early tragedies, Of Mice and Men shows “humanity’s achievement of greatness through and in spite of defeat.”[23] Steinbeck’s novella, however, contains a deceptively simple dramatic structure, one lacking in the grandiose gestures typically associated with the tragic form. The work’s structure may make it readily adaptable to the stage, but there’s no grand design. There are no heroes, or villains in the traditional, Aristotelian sense.[24] As Steinbeck’s working title, Something That Happened, aptly suggests, events in the story simply occur.[25]

But that doesn’t mean Steinbeck’s underlying message is simply that’s the way the cookie crumbles. Though Of Mice and Men is less blatantly a social novel than Grapes of Wrath or In Dubious Battle (Steinbeck’s strike novel), it addresses the elusiveness of the American Dream. It also comments on the false hope of economic prosperity that is frequently dangled in front of middle and lower classes. And Lennie, as Steinbeck specifically states, represents “the inarticulate and powerful yearning of all men” (rather than the “insanity” he is typically associated with).[26]

…

The Wall of Background Behind Of Mice and Men

Though he doesn’t explicitly indicate the historical or social context of his novella, Steinbeck refers to a “wall of background” behind Of Mice and Men.[27] Following the Civil War, a large floating labor class developed in the United States. And, according to a 1917 survey of national labor conditions, “probably no more striking example of extremely seasonal industries exist[ed] than in California.”[28] The report also claims that “the seasonal irregularity of employment [was] so great that there [had] grown up a large class of migratory homeless laborers.”[29] A source associated with the Federal Industrial Relations Commissions indicated that “there is a migratory class of labor in California because there must be. Without them the industries on which California’s fame depends could not exist.”[30]

The conventional wisdom of the day maintained that personal choice was the reason itinerants were on the road. And, that personal failing lead to a life of transience and temporary work. Though noted labor researcher Frederick C. Mills didn’t disregard this factor, he concluded that the “whip of economic necessity” was the primary reason for the existence of the large itinerant class in the state. In Mills’ words (from a 1914 journal he kept while investigating working conditions in California’s Central Valley disguised as a migrant worker), “the constitution of California industry demands an immense reserve labor force of migratory, seasonal workers.”[31]

Farmworkers’ wages were exceedingly low. The living quarters supplied with employment were squalid. And, advancement opportunities were all but non-existent. Even the most ambitious and determined worker typically met with failure, and took to roving out of necessity. Being a farmworker was to be among California’s disenfranchised, a degraded, powerless, and ill-paid fraternity.[32]

Like the “bindle-stiffs” Steinbeck himself worked with “for quite a spell,” George and Lennie never get the little piece of land they keep talking about.[33] And Crooks, the black stablebuck on the ranch, comments on how George and Lennie are just like all the other workers he sees coming through:

I seen hunderds of men come by on the road an’ on the ranches, with their bindles on their back an’ that same damn thing in their heads. Hunderds of them. They come, an’ they quit an’ go on; an’ every damn one of ‘em’s got a little piece of land in his head. An’ never a God damn one of ‘em ever gets it. Just like heaven. Ever’body wants a little piece of lan’. I read plenty of books out here. Nobody never gets to heaven, and nobody gets no land. It’s just in their head. They’re all the time talkin’ about it, but it’s jus’ in their head. [34]

I seen hunderds of men come by on the road an’ on the ranches, with their bindles on their back an’ that same damn thing in their heads. Hunderds of them. They come, an’ they quit an’ go on; an’ every damn one of ‘em’s got a little piece of land in his head. An’ never a God damn one of ‘em ever gets it. Just like heaven. Ever’body wants a little piece of lan’. I read plenty of books out here. Nobody never gets to heaven, and nobody gets no land. It’s just in their head. They’re all the time talkin’ about it, but it’s jus’ in their head. [34]

The idea of owning a little piece of land has taken root in many workers’ heads, but according to Crooks, none of them ever achieves that dream.

Crooks himself embodies another stone in Steinbeck’s “wall of background.” He’s a living reminder of America’s slave-holding economy. Crooks’ twisted back is evidence of the human cost associated with that economy. In case we miss this message, Steinbeck drives his point home with rattling halter chains.[35]

Then there’s Crooks’ living quarters. Not wanted in the bunkhouse, Crooks’ room is separate from the other men. And to drive Steinbeck’s point home once again, there’s a manure pile directly under the window. It’s a striking and powerful depiction of racism – which, needless to say, is a byproduct of the slave-holding economy we continue to grapple with.[36]

Curley’s nameless wife is also defined as property. She’s described (as being heavily made up and wearing red mules adorned with ostrich feathers), but is only ever referred to as “Curley’s wife.”[37] She’s lumped together with the most powerless of the workers, the other chattel of the ranch. So, it’s no coincidence that she’s the one who spells out Lennie’s value within this economic structure, when she calls him a “Machine.”[38]

…

The Potential for Tragic Nobility Isn’t Limited to Kings.

Steinbeck’s blunt approach and rough language, which consistently gets Of Mice and Men banned, are part of his precise reporting of this reality, of this particular time, place, and environment. The point being… this is true to life. “For too long,” Steinbeck wrote to his godmother in 1939, “the language of books was different from the language of men. To the men I write about profanity is adornment and ornament, and is never vulgar and I try to write it so.”[39]

These “dirty details” democratize the realm of Tragedy. Tragedies have traditionally revolved around Kings and other “Great Ones,” (such as Oedipus, or Job). But, Steinbeck makes the very American point that all men are created equal, that Tragedy exists even among the lowly. Even a George, or a Lennie, has the potential for tragic nobility.[40]

As Steinbeck points out in a 1938 issue of Stage magazine:

Of Mice and Men may seem to be unrelieved tragedy, but it is not. A careful reading will show that while the audience knows, against its hopes, that the dream (of Lennie’s) will not come true, the protagonists must, during the play [book] become convinced that it will come true. Everyone in the world has a dream he knows can’t come off but he spends his life hoping it may. This is at once sadness, the greatness, and the triumph of our species. And this belief on stage [within the novella] must go from skepticism to possibility to probability before it is nipped off by whatever the modern word for fate is. And in hopelessness – George is able to rise to greatness – to kill his friend to save him. George is a hero and only heroes are worth writing about. [41]

Of Mice and Men may seem to be unrelieved tragedy, but it is not. A careful reading will show that while the audience knows, against its hopes, that the dream (of Lennie’s) will not come true, the protagonists must, during the play [book] become convinced that it will come true. Everyone in the world has a dream he knows can’t come off but he spends his life hoping it may. This is at once sadness, the greatness, and the triumph of our species. And this belief on stage [within the novella] must go from skepticism to possibility to probability before it is nipped off by whatever the modern word for fate is. And in hopelessness – George is able to rise to greatness – to kill his friend to save him. George is a hero and only heroes are worth writing about. [41]

So, George is a modernist Hero. He’s the little man, who makes the only gesture of control at his disposal, and sacrifices what he’ll lose anyway.[42]

…

Walk a Mile in the Shoes of the Powerless

Steinbeck, as noted earlier, believed that honest literature was about trying to understand our fellow human beings, “what makes them up, and what keeps them going.”[43] And, Of Mice and Men, like all good literature, evokes empathy in the reader. By depicting the lived realities of the economies he examines and their resultant classicism, racism, and sexism – in admittedly ugly but candid terms – he encourages us to walk a mile (as the saying goes) in the shoes of those shaped by the conditions of these economic structures.

Through his characters, Steinbeck appeals to the reader to feel these workers’ desperation and bitter loneliness. He invites us to recognize their dreams of a better life. And he admonishes us to not only consider the real-world moral issues embodied in his characters’ experience, but to confront them.

…

In Conclusion

As pointed out in several places on This Book is Banned, literature shines a light on societal ills. Like the Tragedies of Ancient Greece, contemporary literature urges us to rethink and improve the world we live in. This social/historical layer within Of Mice and Men shines a light on the social issues engendered by an economic structure that creates and benefits from a class of disenfranchised workers. That’s the condition of the state Steinbeck’s Tragedy warns us about. Consistent with the Ancient Tragedies, Steinbeck writes in the hope of inspiring public debate, and a call to action for society to self-correct.

Endnotes:

[1] Gannett, Lewis. “John Steinbeck: Novelist at Work.” The Atlantic Monthly. (December 1945), 58.

[2] Gannett, 58.

[3] “Banned: Of Mice and Men.” American Experience. www.pbs.org ; ALA. “Top 10 Most Challenged Books Lists.” (Of Mice and Men banned).

[4] Sova, 239.

[5] Sova, 239.

[6] ALA. “Top 10 Most Challenged Books of 2020.” Banned & Challenged Books: A Website of the ALA Office for Intellectual (Of Mice and Men banned). Freedom. https://www.ala.org/advocacy/bbooks/frequentlychallengedbooks/top10

[7] ALA. “Banned & Challenged Classics.” Banned & Challenged Books: A Website of the ALA Office for Intellectual (Of Mice and Men banned). Freedom. https://www.ala.org/advocacy/bbooks/frequentlychallengedbooks/classics

[8] ALA. “Banned & Challenged Classics.” (Of Mice and Men banned).

[9]ALA. “Banned & Challenged Classics.” (Of Mice and Men banned).

[10] Schaub, Michael. “John Steinbeck’s ‘Of Mice and Men’ survives censorship attempt in Idaho.” Los Angeles Times. (June 2, 2015).

[11] Scarseth, Thomas. “A Teachable Good Book: ‘Of Mice and Men.’” In Censored Books: Critical Viewpoints. (Pp 388- 394.) Edited by Nicholas J. Karolides et al. (Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2001), 388.

[12] Scarseth, 388.

[13] Shillinglaw, Susan. “Introduction.” Of Mice and Men. (New York: Penguin Books, 1994), 6.

[14] Gannett, 59.

[15] Reinking, Brian. “Robert Burns’s Mouse In Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men and Miller’s Death of a Salesman.” The Arthur Miller Journal. Vol. 8, Number 1 (Spring 2013), 15, 21.

[16] Burch, Michael R. “Robert Burns: Modern English Translations and Original Poems, Songs, Quotes, Epigrams and Bio.” The HyperTexts.

http://www.thehypertexts.com/robert%20burns%20translations%20modern%20english.htm

[17] Steinbeck, John. “Of Mice and Men.” The Portable Steinbeck. (New York: Penguin Books, 1981), 228.

[18] Lisca, Peter. The Wide World of John Steinbeck. (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1981), 136.

[19] Scarseth, Thomas. “A Teachable Good Book: ‘Of Mice and Men.’” In Censored Books: Critical Viewpoints. (Pp 388-394) Edited by Nicholas J. Karolides et al. (Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2002), 388.

[20] Scarseth, 388.

[21] Steinbeck, John. Stage Magazine, January 1938.

[22] Brands, Hal & Charles Edel. The Lessons of Tragedy: Statecraft and World Order. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), 8-10.

[23] Scarseth, 388.

[24] Doyle, Brian Leahy. “Tragedy and the Non-teleological in ‘Of Mice and Men.’” The Steinbeck Review. Vol. 3, Number 2 (Fall 2006), 81.

[25] Parini, Jay. “Of Bindlestiffs, Bad Times, Mice and Men.” New York Times. September 27, 1992.

[26] Gannett, Lewis. “John Steinbeck: Novelist at Work.” The Atlantic Monthly. (December 1945), 58.

[27] Heavilin, Barbara A. “’The wall of background’: Cultural, Political, and Literary Contexts of Steinbeck’s ‘Of Mice and Men.’” The Steinbeck Review. Vol. 15, Number 1, 2018, (pp. 1-16), 1.

[28] Woirol, Gregory R. “Men on the Road: Early Twentieth-Century Surveys of Itinerant Labor in California.” California History. Vol. 70, No. 2 (Summer 1991), 192.

[29] Woirol, 192.

[30] Fitch, John A. “Old and New Labor Problems in California.” The Survey. Volume 32, April 1914 – September 1914), 610.

[31] Woirol, Gregory R. “Men on the Road: Early Twentieth-Century Surveys of Itinerant Labor in California.” California History. Vol. 70, No. 2 (Summer 1991), 198; Mills, Frederick C. “The Hobo and the Migratory Casual on the Road.” Mills, Frederick C. Mills papers, AA.

[32] Shillinglaw, Susan. “Introduction.” Of Mice and Men. (New York: Penguin, 1998), 9.

[33] Parini, Jay. “Of Bindlestiffs, Bad Times, Mice and Men.” New York Times. September 27, 1992.

[34] Steinbeck, “Of Mice and Men,” 293.

[35] Owens, Louis. “Deadly Kids, Stinking Dogs, and Heroes: The Best Laid Plans in Steinbeck’s ‘Of Mice and Men.’” Western American Literature. Vol. 37, No. 3 (Fall 2002), 325.

[36] Hart, Richard E. “Moral Experience in ‘Of Mice and Men’: Challenges and Reflections.” The Steinbeck Review. Vol. 1, No. 2 (Fall 2004), 40.

[37] Steinbeck Of Mice and Men, 254.

[38] Steinbeck Of Mice and Men, 298; Owens, Louis. “Deadly Kids, Stinking Dogs, and Heroes: The Best Laid Plans in Steinbeck’s ‘Of Mice and Men.’” Western American Literature. Vol. 37, No. 3 (Fall 2002), 325.

[39] Scarseth, 389; Shillinglaw, 19.

[40] Scarseth, 389.

[41] John Steinbeck. Stage. January 1938.

[42] Owens “Deadly Kids,” 322.

[43] Hart, 40.

Images:

First-edition dust jacket cover of Of Mice and Men (1937). Illustrated by Ross MacDonald. Published by Covici-Friede. – Scan via Heritage Auctions Lot #36344. Cropped from the original image and lightly retouched., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=91868578

It’s a Regular Greek Tragedy. Dionysus mask. Louvre Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dionysos_mask_Louvre_Myr347.jpg

The Wall of Background Behind Of Mice and Men:

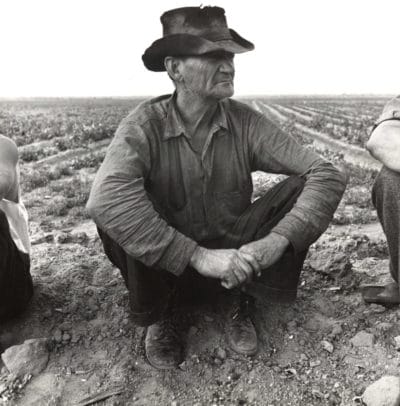

Lange, Dorothea, photographer. On U.S. 101 near San Luis Obispo, California. Itinerant worker. Not the old “Bindle-Stiff” type. United States San Luis Obispo San Luis Obispo County California, 1939. Feb. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017771237/

The Potential for Tragic Nobility Isn’t Limited to Kings:

Lange, Dorothea, photographer. Migrant agricultural worker. Near Holtville, California. Imperial County California Holtville United States, 1937. Feb. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017769658/.

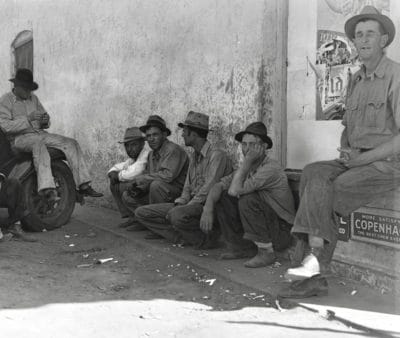

Walk a Mile in the Shoes of the Powerless. Lange, Dorothea, photographer. Migrant agricultural workers, idle in town during the potato harvest. Shafter, California. United States Kern County California Shafter, 1938. June. Photograph. Public Domain via Library of Congress. . https://www.loc.gov/item/2017770608/.

FYI:

This Book is Banned participates in the Amazon.com affiliate program, where we earn a small commission by linking to books (but the price stays the same to you). This allows us to remain free, and ad free. [

Our privacy policy]

Of Mice and Men: A Regular Greek Tragedy

reek tragedies were intended to promote public discussion about how their society could avoid the same tragic mistakes the play deals with. What societal plight is Steinbeck warning us about?

Maybe Steinbeck’s dog Toby knew Of Mice and Men would become one of the most challenged books when he “made confetti” of the first draft.[1] Probably not. But even Steinbeck jokingly wondered whether the setter pup “may have been acting critically.”[2]

And indeed, Of Mice and Men consistently winds up on banned book lists. But, why is Of Mice and Men banned? Like a lot of banned books, Of Mice and Men is frequently challenged for “profanity,” and “offensive language.”[3] It’s been banned for similar reasons somewhere in the United States for decades.

Challenges in the 1970s came from (among other places) Oil City, Pennsylvania; Syracuse, Indiana; and Grand Blanc, Michigan. In 1983, the chair of the Knoxville, Tennessee school board vowed to eradicate all “filthy books” from the local school system, beginning with Of Mice and Men.[4] An Iowa City, Iowa parent challenged the book in 1991 because she didn’t want her daughter to “talk like a migrant worker” when she finished school.[5] And, it was still among the top ten most challenged books in 2020.[6]

Bannings for vulgarity continue. But, why has Of Mice and Men become so controversial? More recent challenges to Steinbeck’s novella include “racist language.”[7] Contemporary objections also involve statements that are “defamatory” to women and the disabled.[8]

Set in California during the Great Depression, Of Mice and Men has also been challenged because it contains “morbid and depressing themes.”[9] A 2015 challenger found it “too ‘negative,’ and ‘dark,’” further stating that the work “is neither a quality story nor a page turner.”[10] Not surprisingly, I beg to differ.

As challenges for “negativity” and “depressing themes” suggest, some people clearly consider literature’s function to be serving up “vicarious ‘happy endings,’” to sugar coat the hard truths of real life.[11] The best writers and readers, however, understand that literature can also be strong medicine – bitter perhaps, but necessary to continued social and emotional health.[12] Needless to say, Of Mice and Men is a dose of this medicine.

“In every bit of honest writing in the world,” Steinbeck noted, “there is a base theme. Try to understand [people], if you understand each other you will be kind to each other.”[13] This sentiment not only underscores concepts addressed elsewhere on this site, more importantly it’s the polar opposite of the thinking behind concerted efforts to ban books that promote diversity.

Steinbeck described his “whole work drive” as being aimed at “making people understand each other.”[14] And, the understanding engendered by Steinbeck’s novella runs deep, which makes it a perfect example of how novels are like a layer cake. By that I mean it contains several levels of meaning and perspectives of interpretation.

Of Mice and Men addresses the human condition on the social/historical level, the mythological level, as well as through a psychological filter. In fact, Steinbeck’s book has so much to offer that this essay will be posted in three segments. Let’s dig into the first installment.

…

It’s a Regular Greek Tragedy.

It all begins with why Of Mice and Men is called Of Mice and Men. Steinbeck’s novella is named for a line in Robert Burns’ 1785 poem To a Mouse, On Turning Her Up In Her Nest With The Plough. The mouse in Burns’ poem embodies the all-too-often futile hope, and fruitless planning that earthly creatures put into the future. Like most Tragic figures, Burns’ mouse is a tangible expression of the fear and misery a being experiences when compelled to vie with forces incomprehensibly bigger than itself.[15]

In proving foresight may be vain

The best laid schemes o’ Mice and Men

Gang aft agley,

An’ lea’e us nought but grief an’ pain,

For promis’d joy! (lines 36-41)

in proving foresight may be vain:

The best-laid schemes of Mice and Men

Go oft awry,

And leave us only grief and pain,

For promised joy! [16]

…

Steinbeck signals from the outset of his novella that mice signify inevitable failure. George is described in mouse-like terms, as “small and quick, dark of face, with restless eyes and sharp, strong features.”[17] And Lennie keeps a dead mouse in his pocket. Lennie carries a mouse in his pocket because he loves to pet soft, furry things. But despite how much he cares for them (or perhaps because he cares so much), no matter how hard he tries Lennie just can’t control his incredible strength, and inevitably kills them by handling them too roughly.[18]

As noted above, one reason Of Mice and Men has “evoked controversy and censorious action” is because it’s “painful” to read.[19] And, I don’t mean that it’s difficult to understand. It hurts to read Of Mice and Men. And that’s because it’s a Tragedy, in the “classic Aristotelian/Shakespearean sense.”[20] Bearing that in mind, it’s very telling that Steinbeck wrote Of Mice and Men in an experimental form he called a “playable novel,” a novel that could be “played from the lines, or a play that could be read.”[21]

It isn’t only that the work’s form parallels that of Tragedy. Of Mice and Men is consistent with Tragedy’s emphasis on plot that revolve around conflicts between opposing if not irreconcilable impulses: mortals and gods for example, law and nature, or individuals and states. And, needless to say, tragedies never end well. The narrative typically culminates in the degradation or destruction of a key individual, coalition, or society.

Though early tragedies were often set in the mythic past, they were purposely (albeit indirectly) intended to promote public debate about current interests and the contemporary condition of the state. In short, for the Greeks tragedies were a form of public education. They were meant to horrify and admonish the citizenry. By shocking and unsettling the audience, tragedies forced discussions of what needed to happen in order to avoid such a fate. So, they weren’t advocating resignation, or conveying a fatalistic message. Tragedies were intended to serve as a warning, and function as a call to action.[22]

Consistent with early tragedies, Of Mice and Men shows “humanity’s achievement of greatness through and in spite of defeat.”[23] Steinbeck’s novella, however, contains a deceptively simple dramatic structure, one lacking in the grandiose gestures typically associated with the tragic form. The work’s structure may make it readily adaptable to the stage, but there’s no grand design. There are no heroes, or villains in the traditional, Aristotelian sense.[24] As Steinbeck’s working title, Something That Happened, aptly suggests, events in the story simply occur.[25]

But that doesn’t mean Steinbeck’s underlying message is simply that’s the way the cookie crumbles. Though Of Mice and Men is less blatantly a social novel than Grapes of Wrath or In Dubious Battle (Steinbeck’s strike novel), it addresses the elusiveness of the American Dream. It also comments on the false hope of economic prosperity that is frequently dangled in front of middle and lower classes. And Lennie, as Steinbeck specifically states, represents “the inarticulate and powerful yearning of all men” (rather than the “insanity” he is typically associated with).[26]

…

The Wall of Background Behind Of Mice and Men

Though he doesn’t explicitly indicate the historical or social context of his novella, Steinbeck refers to a “wall of background” behind Of Mice and Men.[27] Following the Civil War, a large floating labor class developed in the United States. And, according to a 1917 survey of national labor conditions, “probably no more striking example of extremely seasonal industries exist[ed] than in California.”[28] The report also claims that “the seasonal irregularity of employment [was] so great that there [had] grown up a large class of migratory homeless laborers.”[29] A source associated with the Federal Industrial Relations Commissions indicated that “there is a migratory class of labor in California because there must be. Without them the industries on which California’s fame depends could not exist.”[30]

The conventional wisdom of the day maintained that personal choice was the reason itinerants were on the road. And, that personal failing lead to a life of transience and temporary work. Though noted labor researcher Frederick C. Mills didn’t disregard this factor, he concluded that the “whip of economic necessity” was the primary reason for the existence of the large itinerant class in the state. In Mills’ words (from a 1914 journal he kept while investigating working conditions in California’s Central Valley disguised as a migrant worker), “the constitution of California industry demands an immense reserve labor force of migratory, seasonal workers.”[31]

Farmworkers’ wages were exceedingly low. The living quarters supplied with employment were squalid. And, advancement opportunities were all but non-existent. Even the most ambitious and determined worker typically met with failure, and took to roving out of necessity. Being a farmworker was to be among California’s disenfranchised, a degraded, powerless, and ill-paid fraternity.[32]

Like the “bindle-stiffs” Steinbeck himself worked with “for quite a spell,” George and Lennie never get the little piece of land they keep talking about.[33] And Crooks, the black stablebuck on the ranch, comments on how George and Lennie are just like all the other workers he sees coming through:

The idea of owning a little piece of land has taken root in many workers’ heads, but according to Crooks, none of them ever achieves that dream.

Crooks himself embodies another stone in Steinbeck’s “wall of background.” He’s a living reminder of America’s slave-holding economy. Crooks’ twisted back is evidence of the human cost associated with that economy. In case we miss this message, Steinbeck drives his point home with rattling halter chains.[35]

Then there’s Crooks’ living quarters. Not wanted in the bunkhouse, Crooks’ room is separate from the other men. And to drive Steinbeck’s point home once again, there’s a manure pile directly under the window. It’s a striking and powerful depiction of racism – which, needless to say, is a byproduct of the slave-holding economy we continue to grapple with.[36]

Curley’s nameless wife is also defined as property. She’s described (as being heavily made up and wearing red mules adorned with ostrich feathers), but is only ever referred to as “Curley’s wife.”[37] She’s lumped together with the most powerless of the workers, the other chattel of the ranch. So, it’s no coincidence that she’s the one who spells out Lennie’s value within this economic structure, when she calls him a “Machine.”[38]

…

The Potential for Tragic Nobility Isn’t Limited to Kings.

Steinbeck’s blunt approach and rough language, which consistently gets Of Mice and Men banned, are part of his precise reporting of this reality, of this particular time, place, and environment. The point being… this is true to life. “For too long,” Steinbeck wrote to his godmother in 1939, “the language of books was different from the language of men. To the men I write about profanity is adornment and ornament, and is never vulgar and I try to write it so.”[39]

These “dirty details” democratize the realm of Tragedy. Tragedies have traditionally revolved around Kings and other “Great Ones,” (such as Oedipus, or Job). But, Steinbeck makes the very American point that all men are created equal, that Tragedy exists even among the lowly. Even a George, or a Lennie, has the potential for tragic nobility.[40]

As Steinbeck points out in a 1938 issue of Stage magazine:

So, George is a modernist Hero. He’s the little man, who makes the only gesture of control at his disposal, and sacrifices what he’ll lose anyway.[42]

…

Walk a Mile in the Shoes of the Powerless

Steinbeck, as noted earlier, believed that honest literature was about trying to understand our fellow human beings, “what makes them up, and what keeps them going.”[43] And, Of Mice and Men, like all good literature, evokes empathy in the reader. By depicting the lived realities of the economies he examines and their resultant classicism, racism, and sexism – in admittedly ugly but candid terms – he encourages us to walk a mile (as the saying goes) in the shoes of those shaped by the conditions of these economic structures.

Through his characters, Steinbeck appeals to the reader to feel these workers’ desperation and bitter loneliness. He invites us to recognize their dreams of a better life. And he admonishes us to not only consider the real-world moral issues embodied in his characters’ experience, but to confront them.

…

In Conclusion

As pointed out in several places on This Book is Banned, literature shines a light on societal ills. Like the Tragedies of Ancient Greece, contemporary literature urges us to rethink and improve the world we live in. This social/historical layer within Of Mice and Men shines a light on the social issues engendered by an economic structure that creates and benefits from a class of disenfranchised workers. That’s the condition of the state Steinbeck’s Tragedy warns us about. Consistent with the Ancient Tragedies, Steinbeck writes in the hope of inspiring public debate, and a call to action for society to self-correct.

That’s my take on John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men– what’s yours?

Check out this Discussion Guide to get you started.

#John Steinbeck #banned #social commentary #published 1930s

Share This Post, Choose a Platform!

Endnotes:

[1] Gannett, Lewis. “John Steinbeck: Novelist at Work.” The Atlantic Monthly. (December 1945), 58.

[2] Gannett, 58.

[3] “Banned: Of Mice and Men.” American Experience. www.pbs.org ; ALA. “Top 10 Most Challenged Books Lists.” (Of Mice and Men banned).

[4] Sova, 239.

[5] Sova, 239.

[6] ALA. “Top 10 Most Challenged Books of 2020.” Banned & Challenged Books: A Website of the ALA Office for Intellectual (Of Mice and Men banned). Freedom. https://www.ala.org/advocacy/bbooks/frequentlychallengedbooks/top10

[7] ALA. “Banned & Challenged Classics.” Banned & Challenged Books: A Website of the ALA Office for Intellectual (Of Mice and Men banned). Freedom. https://www.ala.org/advocacy/bbooks/frequentlychallengedbooks/classics

[8] ALA. “Banned & Challenged Classics.” (Of Mice and Men banned).

[9]ALA. “Banned & Challenged Classics.” (Of Mice and Men banned).

[10] Schaub, Michael. “John Steinbeck’s ‘Of Mice and Men’ survives censorship attempt in Idaho.” Los Angeles Times. (June 2, 2015).

[11] Scarseth, Thomas. “A Teachable Good Book: ‘Of Mice and Men.’” In Censored Books: Critical Viewpoints. (Pp 388- 394.) Edited by Nicholas J. Karolides et al. (Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2001), 388.

[12] Scarseth, 388.

[13] Shillinglaw, Susan. “Introduction.” Of Mice and Men. (New York: Penguin Books, 1994), 6.

[14] Gannett, 59.

[15] Reinking, Brian. “Robert Burns’s Mouse In Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men and Miller’s Death of a Salesman.” The Arthur Miller Journal. Vol. 8, Number 1 (Spring 2013), 15, 21.

[16] Burch, Michael R. “Robert Burns: Modern English Translations and Original Poems, Songs, Quotes, Epigrams and Bio.” The HyperTexts.

http://www.thehypertexts.com/robert%20burns%20translations%20modern%20english.htm

[17] Steinbeck, John. “Of Mice and Men.” The Portable Steinbeck. (New York: Penguin Books, 1981), 228.

[18] Lisca, Peter. The Wide World of John Steinbeck. (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1981), 136.

[19] Scarseth, Thomas. “A Teachable Good Book: ‘Of Mice and Men.’” In Censored Books: Critical Viewpoints. (Pp 388-394) Edited by Nicholas J. Karolides et al. (Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2002), 388.

[20] Scarseth, 388.

[21] Steinbeck, John. Stage Magazine, January 1938.

[22] Brands, Hal & Charles Edel. The Lessons of Tragedy: Statecraft and World Order. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), 8-10.

[23] Scarseth, 388.

[24] Doyle, Brian Leahy. “Tragedy and the Non-teleological in ‘Of Mice and Men.’” The Steinbeck Review. Vol. 3, Number 2 (Fall 2006), 81.

[25] Parini, Jay. “Of Bindlestiffs, Bad Times, Mice and Men.” New York Times. September 27, 1992.

[26] Gannett, Lewis. “John Steinbeck: Novelist at Work.” The Atlantic Monthly. (December 1945), 58.

[27] Heavilin, Barbara A. “’The wall of background’: Cultural, Political, and Literary Contexts of Steinbeck’s ‘Of Mice and Men.’” The Steinbeck Review. Vol. 15, Number 1, 2018, (pp. 1-16), 1.

[28] Woirol, Gregory R. “Men on the Road: Early Twentieth-Century Surveys of Itinerant Labor in California.” California History. Vol. 70, No. 2 (Summer 1991), 192.

[29] Woirol, 192.

[30] Fitch, John A. “Old and New Labor Problems in California.” The Survey. Volume 32, April 1914 – September 1914), 610.

[31] Woirol, Gregory R. “Men on the Road: Early Twentieth-Century Surveys of Itinerant Labor in California.” California History. Vol. 70, No. 2 (Summer 1991), 198; Mills, Frederick C. “The Hobo and the Migratory Casual on the Road.” Mills, Frederick C. Mills papers, AA.

[32] Shillinglaw, Susan. “Introduction.” Of Mice and Men. (New York: Penguin, 1998), 9.

[33] Parini, Jay. “Of Bindlestiffs, Bad Times, Mice and Men.” New York Times. September 27, 1992.

[34] Steinbeck, “Of Mice and Men,” 293.

[35] Owens, Louis. “Deadly Kids, Stinking Dogs, and Heroes: The Best Laid Plans in Steinbeck’s ‘Of Mice and Men.’” Western American Literature. Vol. 37, No. 3 (Fall 2002), 325.

[36] Hart, Richard E. “Moral Experience in ‘Of Mice and Men’: Challenges and Reflections.” The Steinbeck Review. Vol. 1, No. 2 (Fall 2004), 40.

[37] Steinbeck Of Mice and Men, 254.

[38] Steinbeck Of Mice and Men, 298; Owens, Louis. “Deadly Kids, Stinking Dogs, and Heroes: The Best Laid Plans in Steinbeck’s ‘Of Mice and Men.’” Western American Literature. Vol. 37, No. 3 (Fall 2002), 325.

[39] Scarseth, 389; Shillinglaw, 19.

[40] Scarseth, 389.

[41] John Steinbeck. Stage. January 1938.

[42] Owens “Deadly Kids,” 322.

[43] Hart, 40.

Images:

First-edition dust jacket cover of Of Mice and Men (1937). Illustrated by Ross MacDonald. Published by Covici-Friede. – Scan via Heritage Auctions Lot #36344. Cropped from the original image and lightly retouched., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=91868578

It’s a Regular Greek Tragedy. Dionysus mask. Louvre Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dionysos_mask_Louvre_Myr347.jpg

The Wall of Background Behind Of Mice and Men:

Lange, Dorothea, photographer. On U.S. 101 near San Luis Obispo, California. Itinerant worker. Not the old “Bindle-Stiff” type. United States San Luis Obispo San Luis Obispo County California, 1939. Feb. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017771237/

The Potential for Tragic Nobility Isn’t Limited to Kings:

Lange, Dorothea, photographer. Migrant agricultural worker. Near Holtville, California. Imperial County California Holtville United States, 1937. Feb. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017769658/.

Walk a Mile in the Shoes of the Powerless. Lange, Dorothea, photographer. Migrant agricultural workers, idle in town during the potato harvest. Shafter, California. United States Kern County California Shafter, 1938. June. Photograph. Public Domain via Library of Congress. . https://www.loc.gov/item/2017770608/.

FYI:

Share This Post, Choose a Platform!