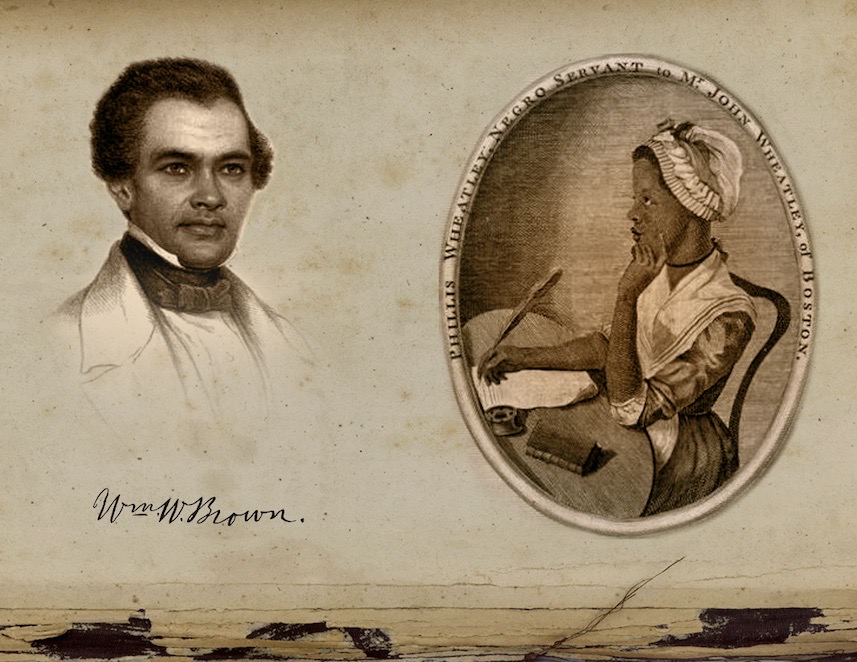

It’s Black History Month: and the spotlight’s on Phillis Wheatley and William Wells Brown

![]() F

F

or our 2024 celebration we’re shining a spotlight on Phillis Wheatley (the first African-American to publish a book of poetry) and William Wells Brown (who wrote the first novel by an African-American).

The story of Black History Month begins in 1915 in Chicago, with African-American historian Carter G. Woodson. Despite being a dues-paying member, Woodson was barred from attending American Historical Association conferences, leading him to believe that the white-dominated historical profession wasn’t interested in Black history.

So Woodson created a separate institutional structure. That organization has come to be known as the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH), an organization dedicated to researching and promoting achievements by Black Americans and other peoples of African descent.

In 1926, the organization launched a week-long celebration, choosing the second week of February to coincide with the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. This event inspired schools and communities across the nation to organize local celebrations, establish history clubs, and host lectures.

Thanks in part to the civil rights movement and a growing awareness of Black identity, by the late 1960s this week-long event evolved into Black History Month on many college campuses.[1]

In 1976, President Gerald Ford officially recognized Black History Month, calling on the public to “seize the opportunity to honor the too-often neglected accomplishments of Black Americans in every area of endeavor throughout our history.”[2]

Let’s take it one step further still. Interest in African-American accomplishments and contributions shouldn’t be limited to a single month. Acknowledge the contributions of African Americans all year long. Especially these days, when books by African American authors are heavily targeted for book banning.

Woodson did, however, establish February as the month to bring African-Americans’ contributions to the fore. So, we’re putting Phillis Wheatley and William Wells Brown in the spotlight – with resources to download their history-making works for free.

Phillis Wheatley is considered the first African-American author of a published book of poetry.[3] She landed in Boston on July 11, 1761, on board a slave ship named Phillis… Yes, disturbingly, that is where her name comes from. Her front teeth were missing, so she was thought to be about seven years old when Susanna Wheatley, wife of a prosperous merchant and tailor, acquired her as a house servant.

Not surprisingly, Phillis didn’t speak English when she arrived in the Wheatley house. What is surprising, is that Susanna Wheatley encouraged her daughter Mary to teach Phillis to read and write, tutoring her in English, Latin, and the Bible. And, by 1765 Phillis had penned the first of many poems.

In 1770, at about the age of seventeen, she wrote an elegy on the death of the Reverend George Whitefield that appeared in several newspapers along the eastern seaboard. Whitfield was the spiritual advisor of English philanthropist, and supporter of abolitionist causes, Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon. Wheatley not only mentioned Hastings in her elegy of Whitfield, she sent the countess a letter of condolence with the poem enclosed.

As a result, Wheatley’s literary reputation grew – on both sides of the ocean. But, so was incredulity at the idea of a black writer of literary works. In an effort to get Phillis’ poetry published, John Wheatley assembled a group of interrogators, in the hope that they would support her claim of authorship.

Just picture it… eighteen “esteemed Bostonians” gathered in a semicircle around Phillis, for the purpose of determining whether she was “qualified” to write poetry.[4] They decided she was. American publishers, however, still refused to print her manuscript. So, Susanna Wheatley took it to London, where the publishing environment was more amenable to black authors. And with the help of Selina Hastings, a collection of Phillis Wheatley’s poems titled Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral was published, establishing her as the first African-American to do so.

From the moment her poems were published, Phillis Wheatley has been accused of “neglect[ing] almost entirely her own state of slavery,” that she was “oblivious to the lot of her fellow blacks.”[5] But, think about it… given the atmosphere of the times, it can hardly be expected that she would write explicit poetry of racial protest. Not only would her poems have remained unpublished, there would most certainly have been dire consequences for having written them at all.

So, Wheatley employed stylistic strategies for conveying these concerns indirectly. She often used suggestion, innuendo, and irony but her message is clear – if, as historian David Grimsted suggests, “one attunes the ear to the subtle intelligence of her ladylike murmur.”[6] Her poetry is yet another example of why it’s important to read beyond simple narrative and plot.

Whether it’s funeral elegies about New England’s elite, or patriotic lyrics about American independence, Wheatley’s central concern is consistently freedom: spiritual freedom, from the shackles of sickness and death; political freedom, from British tyranny; not to mention imaginative freedom (through poetic style), from “the censoring hands of bigoted editors and publishers.”[7]

Download Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral

by Phillis Wheatley here.

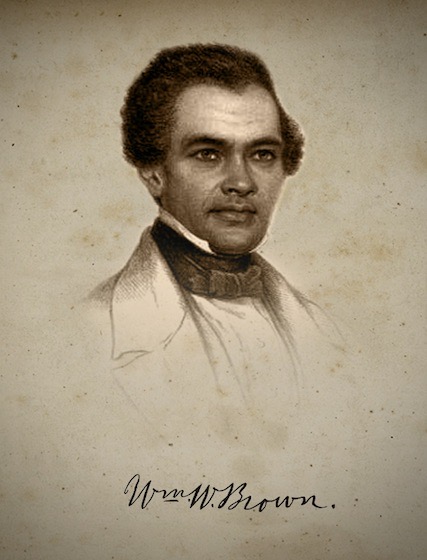

William Wells Brown wrote the first novel by an African-American. Born a slave in Kentucky (1814), he escaped at the age of 19, and became an agent of the Underground Railroad, an antislavery activist, and self-taught writer and orator.

Brown began his career in the abolitionist movement by boarding antislavery lecturers at his home, speaking at local gatherings, and traveling to Haiti and Cuba to investigate emigration possibilities.

His abolitionist career took a turn in 1843, when Buffalo, New York (the city where he lived at the time) hosted a national antislavery convention and the National Convention of Colored Citizens. He attended both conferences, sat on several committees, and befriended a number of black abolitionists, including Charles Lenox Remond and Frederick Douglass.

In 1849 Brown began a lecture of Britain for the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society and remained abroad until 1854. He was elated by the tour. It which gave him time to write, and he understandably enjoyed life among reform circle society.

While abroad, Brown wrote Clotel, a foundational text of the African-American novelistic tradition. It’s the melodramatic story of three generations of black women, all struggling with the constrictions of slavery, miscegenation, and concubinage.

Clotel is a fictionalized account of Thomas Jefferson’s daughters and granddaughters with an enslaved woman named Currer. Brown wrote Clotel amid rumors (which have since been confirmed) that Jefferson had fathered children with Sally Hemmings (a woman enslaved by him). Needless to say, Brown’s book was highly controversial when it was published.[8]

Like Phillis Wheatley’s poetry, Clotel was published in London. But the reason is very different. While Brown was abroad, America passed the Fugitive Slave Law, making it was dangerous for him to return.

Clotel had already been published in England when he was able to do so, made possible in 1854 by British abolitionists who “purchased” Brown’s freedom.[9]

Over the years, Brown wrote four different versions of Clotel, in 1854, 1860-1861, 1864, and finally in 1867. Each rendition was published with a different title, in a different format, one suitable for different readerships.

Little exists in the way of direct records regarding the reception of Clotel’s during the nineteenth century. Perhaps because, as scholar Henry Louis Gates has pointed out, “black fiction was not popularly reviewed.”[10] That said, four editors did publish Brown’s novel, after all. And they did so, seemingly, as a different book each time. This in itself is a testament to its worthiness as a book, as well as a lack of critical reaction successive editors would be aware of.

But, twenty-first century interest in Clotel has been stimulated by new readings resulting from the digitization of Brown’s work. Digitizing allowed scholars to not only chart his deletions and additions, but his reorderings (the greatest of which took place between the 1853 and 1860-1861 versions). Digitization also showed consistencies among the four version, making the unity of Brown’s work(s) evident.

Twentieth-century response to Clotel was initially hindered by a difficulty finding copies of the novel. Not to mention people’s presumption that they were reading the only version of the book. Scholars and critics who did comment considered it stylistically lacking, and its extranarrative material to be a weakness.

Twenty-first-century reception of Clotel, on the hand, has been stimulated by new digitized versions of Brown’s work. With a full comparative reading of all four versions, they carry the reader from a Virginia slave auction in the 1820s to a Mississippi plantation in 1867. The varying renditions function as a single text exposing Southern slavery from Virginia to Louisiana, from antebellum America to postwar America.[11]

More significantly, Clotel is the first instance of an African-American writer dramatizing America’s underlying hypocrisy of democratic principles in the face of institutional slavery.[v]

Download Clotel; or The President’s Daughter here.

Find resources for the compiled versions here.

And, kick off Black History Month with an African-American Read-In. What better books to start with than the groundbreaking works written by these history-making authors?

#History #Celebrations #The Art of Reading #Published in 1770s

#Published in 1850s #banned authors

Endnotes:

[1] “Carter G. Woodson.” Civil Rights Leaders. NAACP

https://naacp.org/find-resources/history-explained/civil-rights-leaders/carter-g-woodson#:~:text=Woodson’s%20devotion%20to%20showcasing%20the,expanded %20into%20Black%20History%20Month.

“Black History Month.” History.com https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/black-history-month

[2] President Gerald R. Ford’s Message on the Observance of Black History Month. February 10, 1976. Ford Library Museum. https://www.fordlibrarymuseum.gov/library/speeches/760074.htm

[3] Gates Jr., Henry Louis. Trials of Phillis Wheatley: The First Black Poet and Her Encounters with the Founding Fathers. New York: Basic Civitas Books, 2010. Pg 5.

[4] Gates Jr., Henry Louis. Phillis Wheatley on Trial. The New Yorker, January 20, 2003. Pg 83.

[5] Loggins, Vernon. The Negro Author. New York: Columbia University Press, 1931. Pg 24.

Gayle, Addison. Black Aesthetic. Garden City: Doubleday, 1971. Pg 384.

[6] Grimsted, David. “Anglo-American Racism and Phillis Wheatley’ s ‘Sable Veil,’ ‘Length’ned Chain,’ and ‘Knitted Heart.'” Women in the Age of the American Revolution. Ed. Ronald Hoffman and Peter J. Albert. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1989. (Pp 338-444). Pg. 349.

[7] Levernier, James A. “Style as Protest in the Poetry of Phillis Wheatley.” Style. Vol. 27, No 2. African-American Poetics. (Pp 172-193) Pg 175.

[8] “Documenting the American South.” https://docsouth.unc.edu/fpn/brownw/bio.html

“Clotel or the President’s Daughter (1853)” Encyclopedia Virginia. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/clotel-or-the-presidents-daughter-1853/

Penguin Books. https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/288980/clotel-by-william-wells-brown/

[9] “Documenting the American South.” https://docsouth.unc.edu/fpn/brownw/bio.html

[10] “Clotel or the President’s Daughter (1853)” Encyclopedia Virginia. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/clotel-or-the-presidents-daughter-1853/

[11] “Clotel or the President’s Daughter (1853)” Encyclopedia Virginia. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/clotel-or-the-presidents-daughter-1853/

[12] Gabler-Hover, Janet. “‘Clotel’,” American History Through Literature, 1820–1870. New York: Scribner’s, 2005 (Pp 248–253). Pg 249.

Images:

Parchment Background on Main Image: Photo by Loren Biser on Unsplash

William Wells Brown: Three Years in Europe: Or, Places I have Seen and People I Have Met. London: Charles Gilpin, 1852. (Flipped.)

Phillis Wheatley: Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral. London: A. Bell, Bookseller, Aldgate, 1773.