T

T

he Lottery ends with a famously disturbing plot twist, one that has provoked controversy since the instant it appeared in The New Yorker. What point was Shirley Jackson making?

The idea for The Lottery popped into Shirley Jackson’s head on the way home from the market, as she pushed her daughter up the hill in the stroller that also held the day’s groceries. The narrative was fairly clear in her mind, and once she got home putting it on paper went “quickly and easily, moving from beginning to end without pause.”[1]

Jackson’s story seems to have been inspired by a typical, “all-American,” domestic situation. A mother and her young child making preparations for the family’s evening meal – what could be more benevolent than that? So, what made such a story so controversial? Why was The Lottery banned?

The story Jackson wrote that afternoon ends with a famously shocking plot twist, one that provoked controversy the instant it appeared in The New Yorker. The Lottery has been described as a story that “demands a reaction from its reader,” and boy, did readers react![2] Hundreds cancelled their subscriptions.[3] Many of them took Jackson’s story for a factual report. And vehement letters addressed directly to Jackson filled the mailroom, describing her story as “perverted,” “horrible and gruesome,” not to mention “in incredibly bad taste.”[4]

Reasons why The Lottery is routinely banned by public schools fall along similar lines. Jackson’s work was challenged at the Salem-Keizer School District in Oregon for its depiction of “morbid and grotesque ideas.”[5] It was challenged in Webster City, Iowa for being “like Friday the 13th.” The school administrator specifically took offense to the story’s insinuation “that a child is stoning a parent.”[6]

Those who set out to ban The Lottery from school curriculums saw it as an attack on the family by way of undermined traditions. Challengers interviewed for an article in the journal Social Education expressed concern that reading Jackson’s story causes students “to question their values, traditions, and religious beliefs.”[7] And that instilling these thoughts in young readers’ minds is a subtle means of destroying the family unit.

These challengers may not be taking The Lottery as factual reporting, the way many who cancelled their New Yorker subscriptions did. But like those disgruntled subscribers, their objections are the result of a shallow, deficient interpretation of Jackson’s iconic story, of not thinking past the narrative much less their noses.

Though challengers’ observation about The Lottery questioning tradition isn’t inaccurate, it is terribly misguided. The point Jackson makes is more nuanced, and significantly more profound than a call to spit in the eye of tradition out of sheer defiance. The real question here is not, “how could she?!” but “why does Jackson advocate questioning tradition?” And no… it isn’t a devious plan to destroy the American family.

_________

Shirley Jackson’s Raw Materials.

Who knows what was going through Shirley Jackson’s head as she walked home from the market, just before she put her daughter Joanne in the playpen, the frozen vegetables in the freezer, and The Lottery down on paper. What was so compelling that the story flowed “quickly and easily, moving from beginning to end without pause?”[8]

It might have been the feeling of being a “frozen out” faculty wife by the townspeople where she lived, or the painful awareness of anti-Semitism Jackson had acquired from personal experience.[9] Perhaps it was the anthropology book her husband recently brought home, or the witchcraft she’d been interested in since college. Maybe the motivating factor was world events, the disturbing revelations about the Holocaust that emerged from the Nuremberg trials just a couple years earlier.[10] These were the raw materials that went into the making of The Lottery, to be sure. And they most certainly inform the shape the work takes. But what must have really been on Jackson’s mind as this story poured forth, was the notion that ordinary people are capable of horrific acts. She as much as says so in the San Francisco Chronicle:

I suppose I hoped, by setting a particularly brutal ancient rite in the present and in my own village, to shock the story’s readers with a graphic dramatization of the pointless violence and general inhumanity in their own lives.[11]

And shock them she did. Significantly, Jackson’s story came out while American citizens were still trying to process the distressing reports about the Nazis’ persecution of Europe’s Jews, Romani people, and other victims. Many Americans were confidently insisting that nothing like that could ever happen here. Then along comes The Lottery, with a disturbing ending that blows a hole in American complacency – straight into the mailboxes of The New Yorker subscribers, no less.[12]

The juxtaposition of ritual murder with modern small-town America is pretty jarring. Especially when the ritual murder is carried out by stoning. As noted, this narrative certainly packs an emotional wallop. And when read for more than plot, when attention is paid to The Lottery’s structure and the symbolism Jackson employs, we see a summary of humankind’s savage past, as well as what her husband referred to as an “anatomy of our times.”[13] And what becomes clear is that humanity is not at the mercy of a “murky, savage id.”[14] No, we are the victim of an unexamined culture and unchanging traditions which, like the lottery in Jackson’s story, actually engenders a cruelty not rooted in our inherent makeup. [15] That is Jackson’s message. It’s also the very real horror within The Lottery.

_________

What Does the Three-Legged Stool Symbolize?

The obvious similarity between the village’s lottery and scapegoat traditions has been pointed out on many occasions. And this parallel gives us insight into the symbolic nature of the three-legged stool that’s placed in the center of the village square. Significantly, it is on this stool that the “the black wooden box,” the mechanism for conducting the lottery, rests.[16] The three-legged stool embodies examples of scapegoating, the raw materials mentioned above that inform The Lottery and its symbolism. One leg stands for the ancient scapegoat ritual itself, which Jackson had become familiar with through the anthropology book her husband brought home. Another leg signifies the Salem Witch Trials, made all the more relevant given her interest in witchcraft and magic. And the third leg represents the Nazi-perpetrated Holocaust, still fresh in the minds of the entire world.

_________

What are the Origins of Scapegoating?

At its root, the scapegoat tradition is about purging evil, clearing out the ills that have been plaguing the community that is performing the rite. And the scapegoat is literally the vehicle for carrying this evil away. Scapegoating rituals can be found in many cultures, but the term comes from a rite in the biblical book of Leviticus. As in The Lottery, the sacrifice is chosen by lots, in this case a goat. The animal is symbolically marked with the inequities of the people and sent off into the wilderness. Hence, “(e)scape” goat. The goat doesn’t get too far, though, because it’s someone’s job to follow him and drive him off a cliff – backwards. The poor guy never sees it coming. The goat is clearly destroyed, and with it, the evil he was carrying.[17]

But not all scapegoats are goats. In some cultures, they’re human. When it comes to human sacrifice, the first civilization that comes to mind is probably the Aztecs, but they’re certainly not the only ones. Accounts exist from around the world and across the ages, from Ancient Greece to as late as the nineteenth century in the Pacific Islands.[18] Whatever shape the scapegoat takes, the “general clearance of evil” described above (the purpose most often associated with the scapegoat tradition), occurred periodically. For agrarian cultures, that was typically at a time that coincided with planting or harvest.[19] Though June 27th doesn’t strictly align with either of those agricultural events, Mr. Warner’s maxim “Lottery in June, corn be heavy soon” is clearly a nod in that direction.[20]

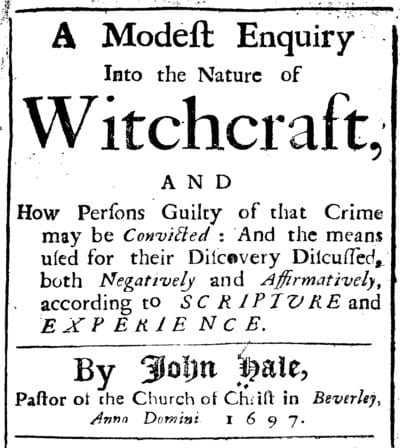

Though the practice of sacrificing human scapegoats is no longer ritualized, that doesn’t mean it no longer happens. The witchcraft hysteria that continues to inform New England culture, and the Salem Witch Trials specifically, are nothing if not scapegoating. Women labeled as witches (the operative word being labeled), were executed in order to purge their village of Satanic influence. And the Nazi’s effort to purify Germany by “exterminating” Jews, the Romani people and other groups, is scapegoating by industrial means. These are certainly not the only examples of human scapegoating that have taken place after the Age of Enlightenment, but they are the ones that inform The Lottery.

_________

Scapegoating in the Salem Witch Trials.

Jackson never explicitly tells the reader where the lottery takes place. And there’s a reason for that. If she did, her story would no longer be about “anytown America.” But the clues she gives us about the village are important to our understanding of The Lottery beyond simple ambiance. It’s a small farming community of about 300 people. And most of the population has a family name with Anglo-Saxon origins. The last detail Jackson gives us is that the land yields an abundance of stones, a fact critical to the story beyond the obvious reason. These clues suggest that New England is the locale of the story. When taken in total, this information points to the region’s history of witch trials and persecutions, especially when the village’s patriarchal power structure gets thrown into the mix. And the fact that critical scenes in in a young adult book Jackson wrote about witchcraft hysteria (The Witchcraft of Salem Village) parallel scenarios in The Lottery, substantiates an intended allusion to witch trials.[21]

An important parallel between Massachusetts during the witchcraft hysteria and the village where Jackson lived is the power dynamic between genders. In both cases, the targeted women respond to the pressure of male authority by betraying other women. It’s a classic “divide and conquer” scenario. The way this plays out in The Lottery is a testament to how successfully the male-dominated order has been imposed on the village’s women.[22] Tessie’s right when she claims that the lottery wasn’t fair. But not because they didn’t give her husband “enough time to choose.”[23] It wasn’t fair, intentionally or not, because the system was designed from a patriarchal perspective.

So, how does the lottery work? The village’s lottery seems random to all but the most meticulous of readers because, by and large, we still accept being classified by surname (in other words, our father’s name) as the standard. Drawing lots according to the household/ father’s name skews the odds toward “women of a certain age,” especially those with few, or female children. In terms of avoiding the black dot, younger is better because a woman’s children are still at home. Having more children dilutes the possibility of drawing the black dot. And having a lot of boys is better still because they won’t marry out of the family and increase their mother’s risk as she ages. Tessie’s betrayal of her married daughter, by insisting that she take her chances with the Hutchinsons, is born of this inequity.[24]

Our trip through the lottery process in Jackson’s village reveals a parallel between the demographic most at risk in The Lottery, and the women most frequently persecuted as witches. The witch trials of Puritan Massachusetts were founded on a patriarchal interpretation of the myth of Eve and her role in The Fall. A second layer of patriarchal thought deems her, and by extension all women, more susceptible to the demonic than men – at least according to a couple of Dominican inquisitors from 1486. And women labeled as witches (the operative word being labeled), were executed in an effort to purify their village of Satanic influence.

The group most vulnerable to accusations of witchcraft was women between forty and sixty. That’s the same segment of society most likely to draw the black dot in The Lottery. In Puritan Massachusetts, accusations of witchcraft served to crush a particular class of women, insufficiently docile women who failed to fit into their assigned role of submissive helpmeet, those who spoke their minds or attempted to run their own affairs.[25]

So, why was Tessie Hutchinson stoned to death The Lottery? Tessie is precisely this type of woman. She shows up late and must weave her way through the crowd to reach her husband, who had been waiting quite some time for her to arrive. Tessie barks at her husband to “get up there,” when it’s his turn to select a slip of paper from the wooden box.[26] And she certainly isn’t docile when she shouts and yells, challenging the fairness of the lottery and by extension male authority.

Unfortunately for Tessie, much like the women of Puritan Massachusetts,[27] the other women in the village seem to have internalized the ominous lesson they were intended to learn, which is to keep their places in the established order.[28] For, it’s only women Jackson calls out by name as charging toward Tessie, stones in hand as the story ends.

_________

More Scapegoating in the Holocaust.

News from the Nuremberg trials, and revelations about the Holocaust were fresh in everyone’s mind. The horrific stories were more personal for Jackson than many Americans because, as the wife of a Jewish husband, she had first-hand experience with anti-Semitism. And though Jackson consistently refused to give a concise explanation of The Lottery, she did tell a friend that the story has to do with anti-Semitism.[29]

The scapegoating the Nazis employed on this colossal scale was an outcome of the ideological (mis)appropriation of Germany’s mythological heritage. The original concept was grounded in the idea that a proper nation, or Volk, requires a particular holistic unity. This totality must be comprised of a natural environment, a language and history rooted in a deep past and rural population, and the expression of that history in an indigenous mythology. The culture that emerged from this sentiment became radicalized, crystallizing as völkisch nationalism in the first third of the 20th century. [30] Anyone perceived as not fulfilling all aspects of this unity was painted as an enemy. And in an effort to “purify” the Volk, those deemed outsiders were targeted. Though Jews were considered the primary enemy, the Romani people and a number of other groups were also among those who collectively fulfilled the role of scapegoat.[31]

Jackson’s story echoes the reported experience of Holocaust survivors in several respects. Let’s start with the hard truth that children are not exempt in either scenario. Like the little girl who wore the red coat in the film Schindler’s List, Davy Hutchinson is at risk as much as everybody else. And that reality is about as disturbing and heart wrenching as it gets.

But more significant in terms of The Lottery’s narrative and its structure, is the fact that the ritual murder in The Lottery is alluded to, although not seen by the reader. Like the execution of survivors’ family members, the act of stoning in The Lottery isn’t witnessed directly. Consequently, in both instances, the focus becomes the very personal experience of the selection process, which needless to say determines between “death or reprieve.”[32] Which is why everyone sighs when little Davy’s paper was blank.

The Lottery’s narrative is the selection process. Jackson’s story is essentially a detailed description of the mechanics of the village’s lottery. And the following high points of that process sound an awful lot like the frequent selections that took place in concentration camps. Flanked by Mr. Graves and Mr. Martin, Mr. Summers declares the lottery open. “A sudden hush fell on the crowd as Mr. Summers cleared this throat and looked at the list. ‘All ready?’ he called.”[33] Once it was determined that this year’s victim would come from the Hutchinson household, each member of the family is called forth as they anxiously draw their individual lots.

This scenario is strikingly similar to the selection process Elie Weisel recounts in Night, the autobiographical account of his experience in both Auschwitz and Buchenwald:

Three SS officers surrounded the notorious Dr. Mengele, the very same who had received us in Birkenau. The Blockälteste [barracks leader] attempted a smile. He asked us: “Ready?” Yes, we were ready. So were the SS doctors. Dr. Mengele was holding a list: our numbers. He nodded to the Blockälteste: we can begin! As if this were a game… I had one thought: not to have my number taken down and not to show my left arm.[34]

There are enough accounts of the numerous and varied atrocities visited upon the people that comprise the Nazis’ collective scapegoat to fill a library, and they have. Yet, Weisel’s testimony to what occurred in the camps makes it clear that the most terrible word, the one feared more than any other, was selection.[35] Jackson’s villagers must feel the same way about the term lottery.

_________

The Lottery’s Deteriorating Ritual.

Jackson points out that the original box the villagers used for the lottery had been “lost long ago.” The fact that it was lost, rather than destroyed by termites for example or burned in a barn fire, suggests that over time the villagers have been turning away from the antiquated pagan beliefs this ritual is clearly grounded in. There was once a ritual salute. The lottery official no longer stands “just so.” He doesn’t sing the “tuneless chant” anymore.[36] And at one time there might have been something about him walking among the people… maybe. But these days, the lottery is something to be rushed through so everyone can “get home for noon dinner.”

This evolution of the village’s ritual reveals that the appearance of progress in society is an illusion. Letting go of antiquated pagan beliefs makes it appear that the people in the village have become more enlightened. But, they haven’t. As Jackson put it, “although the villagers had forgotten the ritual and lost the original black box, they still remembered to use stones.”[37] The point being, though the villagers have let go of most aspects of this pagan ritual they are not actually more civilized. The brutality at its core remains fully intact. And to drive that point home, what the tradition has evolved into, is simply an excuse for violence.

The most damning thing about this situation is that collectively, the townspeople could bring the lottery to an end. But, like the citizens of Salem who get drawn into the cycle of accusation rather than question church tradition, they don’t. They perpetuate this annual murder by teaching it to the younger generations. Someone not only helps Davy Hutchinson draw his slip of paper, they place stones in his little hand. And they do so simply for the sake of upholding tradition. We know this is the only motivation for continuing the lottery, because Old Man Warner’s only response to Mrs. Adams’ suggestion to give it up is nothing more substantial than, “there’s always been a lottery.”[38]

_________

In Conclusion

It’s no accident that Jackson chose stoning rather than a modern, mechanized method of ritual murder à la Nazi Germany, or the hanging employed in The Salem Witch Trials for that matter. She elected to use stoning, because pelting someone to death with rocks is as primitive as it gets. The symbolism is double-edged. Stoning not only speaks to the antiquity of the scapegoat tradition, most importantly it’s a statement about the current state of humanity. Jackson’s choice of stoning is her not too subtle way of saying we’re just as savage as we ever were.

Jackson paints a pretty dismal picture. She seems to be saying that these villagers (and by that she means the whole of humankind) will never be free of their primitive nature. At least, not until enough of them have been affected adversely enough by the horror of their tradition that they reject it and, as Mrs. Adams implies, destroy the box altogether. Or they fashion a new box, one that reflects their current social conditions and sustains them rather than pitting them against each other.[39] Until that happens, Tessie Hutchinson may be the only loser, but no one is a winner.

Endnotes:

[1] Jackson, Shirley. “Biography of a Story.” Shirley Jackson: Novels & Stories. Edited by Joyce Carol Oates. (New York: Library of America, 2010), 787.

[2] Gahr, Elton. “Criticism of “The Lottery” by Shirley Jackson: Reactions upon the Initial Publication & Today.” Bright Hub Education.com August 31, 2011; Jackson, “Biography of a Story;” Cohen, Gustavo Vargas. Shirley Jackson’s Legacy: A Critical Commentary on the Literary Reception. Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul. July 2012, 17.

[3] Jackson, “Biography of a Story;” Cohen Shirley Jackson’s Legacy, 17.

[4] Jackson, “Biography of a Story,” 797, 799, 797.

[5] ACLU-or.org Oregon Library School Challenges 1979-July 2015.

[6] Brown, Jean E., Ed. SLATE on Intellectual Freedom. (Urbana Ill: National Council of Teachers of English,1994), 24.

[7] Brown, Bill, et al. “The Censoring of “The Lottery.’” The English Journal. Feb., 1986, Vol. 75, No. 2.

[8] Jackson, Shirley. “Biography of a Story.” Shirley Jackson: Novels & Stories. Edited by Joyce Carol Oates. (New York: Library of America, 2010), 787; Franklin, Ruth. Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life. (New York: W.W. Norton & Co, 2016), 222.

[9] Heller, Zoe. “The Haunted Mind of Shirley Jackson.” The New Yorker. October 17, 2016; Oppenheimer, Judy. “The Haunting of Shirley Jackson.” The New York Times. July 3, 1988.

[10] Franklin, Ruth. Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life. (New York: W.W. Norton & Co, 2016), 221, 217, 234; Hyman, Stanley Edgar. “Preface,” The Magic of Shirley Jackson, by Shirley Jackson (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1965), ix.

[11] Franklin, Ruth. “The Lottery Letters.” The New Yorker. June 25, 2013.

[12] Bogert, Edna. “Censorship and ‘The Lottery.’” The English Journal. Vol. 74, No. 1 (Jan., 1985), 47; Yarmove, Jay A. “Jackson’s ‘The Lottery.’” The Explicator. Vol. 52, Issue 4. *Summer, 1994), 242-245.

[13] Hyman The Magic of Shirley Jackson, ix.

[14] Nebeker, Helen E. “’The Lottery’ Symbolic Tour de Force.” American Literature. (Mar. 1974, Vol. 46. No. 1), 100-102

[15] Nebeker, “’The Lottery’ Symbolic Tour de Force.” 101-102.

[16] Nebeker “’The Lottery’ Symbolic Tour de Force.” 103; Jackson, Shirley. “The Lottery.” The New Yorker. June 26, 1948.

[17] Cooper, Howard. “Some Thoughts on ‘Scapegoating’ and its origins in Leviticus 16.” European Judaism: A Journal for the New Europe. Vol. 41, No. 2 (Autumn 2008).

[18] Frazer, James George. The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion. (New York: MacMIllan Company, 1925), 579; martin, John. An Account of the Natives of the Tonga Islands. (London: John Murray, 1817), 229.

[19] Frazer The Golden Bough, 575.

[20] Jackson The Lottery.

[21] Oehlschlaeger, Fritz. “The Stoning of Mistress Hutchinson: Meaning and Context in ‘The Lottery.’” Essays in Literature. Vol. 15, Issue 2 (Fall 1988), 263.

[22] Oehlschlaeger, “The Stoning of Mistress Hutchinson,” 262-263.

[23] Jackson The Lottery.

[24] Whittier, Gayle. “’The Lottery’ as Misogynist Parable.” Women’s Studies. Vol. 18. (1991), 357.

[25] Radford-Ruether, Rosemary. Sexism and God-Talk. (Boston: Beacon Press, 1993), 171-172.

[26] Jackson The Lottery.

[27] In her book Sexism and God-talk, Rosemary Radford-Ruether argues that the witchcraft persecutions in Puritan Massachusetts began to decline by 1700 at least in part because they had served their purpose and were no longer necessary to enforce the patriarchal order.

[28] Radford-Ruether Sexism and God-Talk, 171-172.

[29] Franklin Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life, 234.

[30] Von Schnurbein, Stefanie. Norse Revival: Transformations of Germanic Neopaganism. (Boston: Brill, 2016), 17.

[31] “Defining the Enemy.” Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

[32] Weisel, Elie. Night. (New York: Hill and Wang, 2006), 70.

[33] Jackson The Lottery.

[34] Weisel Night, 71-72.

[35] Weisel Night, 70; Dwork, Debórah, and Robert Jan Van Pelt. Auschwitz. (New York: W. W. Norton, 2008), 353.

[36] Jackson The Lottery.

[37] Jackson The Lottery.

[38] Jackson, The Lottery; Robinson, Michael. “Shirley Jackson’s ‘The Lottery’ and Holocaust Literature.” Humanities. 8.1 (2019).

[39] Nebeker, “‘The Lottery’ Symbolic Tour de Force.” 107.

Images:

1 Cover. Jackson, Shirley. The Lottery. (New York: Popular Library, 1976). Image is supplied by Amazon.com via Internet Speculative Fiction Data Base. http://www.isfdb.org/cgi-bin/pl.cgi?413754 . The original image has been cropped. It is utilized under a Creative Commons license. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/legalcode.

2 New England Village. Photo by Yuval Zukerman on Unsplash

3 Mountain Goat. Photo by Maria Teneva on Unsplash

4 Hale, John, and John Higginson. A modest enquiry into the nature of witchcraft, and how persons guilty of that crime may be convicted: and the means used for their discovery discussed, both negatively and affimatively, according to Scripture and experience. By John Hale, Pastor of the Church of Christ in Beverley, anno domini 1697. [Six lines of Scripture texts]. Printed by B. Green, and J. Allen, for Benjamin Eliot under the town house, 1702. Eighteenth Century Collections Online, link.gale.com/apps/doc/CB0127095065/ ECCO?u=sain79627&sid=bookmark-ECCO&xid=f70c042b&pg=1. Accessed 10 Jan. 2022.

5 Auschwitz Concentration Camp. Photo via www.auschwitz.org

6 Stonehenge. Public Domain via www.goodfreephotos.com

https://www.goodfreephotos.com/albums/england/other-england/stonehenge-under-the-sunset-skies.jpg

FYI:

This Book is Banned participates in the Amazon.com affiliate program, where we earn a small commission by linking to books (but the price remains the same to you). This allows us to remain free, and ad free. [Our privacy policy]

The Lottery: Who’s the Lucky Scapegoat?

he Lottery ends with a famously disturbing plot twist, one that has provoked controversy since the instant it appeared in The New Yorker. What point was Shirley Jackson making?

The idea for The Lottery popped into Shirley Jackson’s head on the way home from the market, as she pushed her daughter up the hill in the stroller that also held the day’s groceries. The narrative was fairly clear in her mind, and once she got home putting it on paper went “quickly and easily, moving from beginning to end without pause.”[1]

Jackson’s story seems to have been inspired by a typical, “all-American,” domestic situation. A mother and her young child making preparations for the family’s evening meal – what could be more benevolent than that? So, what made such a story so controversial? Why was The Lottery banned?

The story Jackson wrote that afternoon ends with a famously shocking plot twist, one that provoked controversy the instant it appeared in The New Yorker. The Lottery has been described as a story that “demands a reaction from its reader,” and boy, did readers react![2] Hundreds cancelled their subscriptions.[3] Many of them took Jackson’s story for a factual report. And vehement letters addressed directly to Jackson filled the mailroom, describing her story as “perverted,” “horrible and gruesome,” not to mention “in incredibly bad taste.”[4]

Reasons why The Lottery is routinely banned by public schools fall along similar lines. Jackson’s work was challenged at the Salem-Keizer School District in Oregon for its depiction of “morbid and grotesque ideas.”[5] It was challenged in Webster City, Iowa for being “like Friday the 13th.” The school administrator specifically took offense to the story’s insinuation “that a child is stoning a parent.”[6]

Those who set out to ban The Lottery from school curriculums saw it as an attack on the family by way of undermined traditions. Challengers interviewed for an article in the journal Social Education expressed concern that reading Jackson’s story causes students “to question their values, traditions, and religious beliefs.”[7] And that instilling these thoughts in young readers’ minds is a subtle means of destroying the family unit.

These challengers may not be taking The Lottery as factual reporting, the way many who cancelled their New Yorker subscriptions did. But like those disgruntled subscribers, their objections are the result of a shallow, deficient interpretation of Jackson’s iconic story, of not thinking past the narrative much less their noses.

Though challengers’ observation about The Lottery questioning tradition isn’t inaccurate, it is terribly misguided. The point Jackson makes is more nuanced, and significantly more profound than a call to spit in the eye of tradition out of sheer defiance. The real question here is not, “how could she?!” but “why does Jackson advocate questioning tradition?” And no… it isn’t a devious plan to destroy the American family.

_________

Shirley Jackson’s Raw Materials.

Who knows what was going through Shirley Jackson’s head as she walked home from the market, just before she put her daughter Joanne in the playpen, the frozen vegetables in the freezer, and The Lottery down on paper. What was so compelling that the story flowed “quickly and easily, moving from beginning to end without pause?”[8]

It might have been the feeling of being a “frozen out” faculty wife by the townspeople where she lived, or the painful awareness of anti-Semitism Jackson had acquired from personal experience.[9] Perhaps it was the anthropology book her husband recently brought home, or the witchcraft she’d been interested in since college. Maybe the motivating factor was world events, the disturbing revelations about the Holocaust that emerged from the Nuremberg trials just a couple years earlier.[10] These were the raw materials that went into the making of The Lottery, to be sure. And they most certainly inform the shape the work takes. But what must have really been on Jackson’s mind as this story poured forth, was the notion that ordinary people are capable of horrific acts. She as much as says so in the San Francisco Chronicle:

I suppose I hoped, by setting a particularly brutal ancient rite in the present and in my own village, to shock the story’s readers with a graphic dramatization of the pointless violence and general inhumanity in their own lives.[11]

And shock them she did. Significantly, Jackson’s story came out while American citizens were still trying to process the distressing reports about the Nazis’ persecution of Europe’s Jews, Romani people, and other victims. Many Americans were confidently insisting that nothing like that could ever happen here. Then along comes The Lottery, with a disturbing ending that blows a hole in American complacency – straight into the mailboxes of The New Yorker subscribers, no less.[12]

The juxtaposition of ritual murder with modern small-town America is pretty jarring. Especially when the ritual murder is carried out by stoning. As noted, this narrative certainly packs an emotional wallop. And when read for more than plot, when attention is paid to The Lottery’s structure and the symbolism Jackson employs, we see a summary of humankind’s savage past, as well as what her husband referred to as an “anatomy of our times.”[13] And what becomes clear is that humanity is not at the mercy of a “murky, savage id.”[14] No, we are the victim of an unexamined culture and unchanging traditions which, like the lottery in Jackson’s story, actually engenders a cruelty not rooted in our inherent makeup. [15] That is Jackson’s message. It’s also the very real horror within The Lottery.

_________

What Does the Three-Legged Stool Symbolize?

The obvious similarity between the village’s lottery and scapegoat traditions has been pointed out on many occasions. And this parallel gives us insight into the symbolic nature of the three-legged stool that’s placed in the center of the village square. Significantly, it is on this stool that the “the black wooden box,” the mechanism for conducting the lottery, rests.[16] The three-legged stool embodies examples of scapegoating, the raw materials mentioned above that inform The Lottery and its symbolism. One leg stands for the ancient scapegoat ritual itself, which Jackson had become familiar with through the anthropology book her husband brought home. Another leg signifies the Salem Witch Trials, made all the more relevant given her interest in witchcraft and magic. And the third leg represents the Nazi-perpetrated Holocaust, still fresh in the minds of the entire world.

_________

What are the Origins of Scapegoating?

At its root, the scapegoat tradition is about purging evil, clearing out the ills that have been plaguing the community that is performing the rite. And the scapegoat is literally the vehicle for carrying this evil away. Scapegoating rituals can be found in many cultures, but the term comes from a rite in the biblical book of Leviticus. As in The Lottery, the sacrifice is chosen by lots, in this case a goat. The animal is symbolically marked with the inequities of the people and sent off into the wilderness. Hence, “(e)scape” goat. The goat doesn’t get too far, though, because it’s someone’s job to follow him and drive him off a cliff – backwards. The poor guy never sees it coming. The goat is clearly destroyed, and with it, the evil he was carrying.[17]

But not all scapegoats are goats. In some cultures, they’re human. When it comes to human sacrifice, the first civilization that comes to mind is probably the Aztecs, but they’re certainly not the only ones. Accounts exist from around the world and across the ages, from Ancient Greece to as late as the nineteenth century in the Pacific Islands.[18] Whatever shape the scapegoat takes, the “general clearance of evil” described above (the purpose most often associated with the scapegoat tradition), occurred periodically. For agrarian cultures, that was typically at a time that coincided with planting or harvest.[19] Though June 27th doesn’t strictly align with either of those agricultural events, Mr. Warner’s maxim “Lottery in June, corn be heavy soon” is clearly a nod in that direction.[20]

Though the practice of sacrificing human scapegoats is no longer ritualized, that doesn’t mean it no longer happens. The witchcraft hysteria that continues to inform New England culture, and the Salem Witch Trials specifically, are nothing if not scapegoating. Women labeled as witches (the operative word being labeled), were executed in order to purge their village of Satanic influence. And the Nazi’s effort to purify Germany by “exterminating” Jews, the Romani people and other groups, is scapegoating by industrial means. These are certainly not the only examples of human scapegoating that have taken place after the Age of Enlightenment, but they are the ones that inform The Lottery.

_________

Scapegoating in the Salem Witch Trials.

Jackson never explicitly tells the reader where the lottery takes place. And there’s a reason for that. If she did, her story would no longer be about “anytown America.” But the clues she gives us about the village are important to our understanding of The Lottery beyond simple ambiance. It’s a small farming community of about 300 people. And most of the population has a family name with Anglo-Saxon origins. The last detail Jackson gives us is that the land yields an abundance of stones, a fact critical to the story beyond the obvious reason. These clues suggest that New England is the locale of the story. When taken in total, this information points to the region’s history of witch trials and persecutions, especially when the village’s patriarchal power structure gets thrown into the mix. And the fact that critical scenes in in a young adult book Jackson wrote about witchcraft hysteria (The Witchcraft of Salem Village) parallel scenarios in The Lottery, substantiates an intended allusion to witch trials.[21]

An important parallel between Massachusetts during the witchcraft hysteria and the village where Jackson lived is the power dynamic between genders. In both cases, the targeted women respond to the pressure of male authority by betraying other women. It’s a classic “divide and conquer” scenario. The way this plays out in The Lottery is a testament to how successfully the male-dominated order has been imposed on the village’s women.[22] Tessie’s right when she claims that the lottery wasn’t fair. But not because they didn’t give her husband “enough time to choose.”[23] It wasn’t fair, intentionally or not, because the system was designed from a patriarchal perspective.

So, how does the lottery work? The village’s lottery seems random to all but the most meticulous of readers because, by and large, we still accept being classified by surname (in other words, our father’s name) as the standard. Drawing lots according to the household/ father’s name skews the odds toward “women of a certain age,” especially those with few, or female children. In terms of avoiding the black dot, younger is better because a woman’s children are still at home. Having more children dilutes the possibility of drawing the black dot. And having a lot of boys is better still because they won’t marry out of the family and increase their mother’s risk as she ages. Tessie’s betrayal of her married daughter, by insisting that she take her chances with the Hutchinsons, is born of this inequity.[24]

Our trip through the lottery process in Jackson’s village reveals a parallel between the demographic most at risk in The Lottery, and the women most frequently persecuted as witches. The witch trials of Puritan Massachusetts were founded on a patriarchal interpretation of the myth of Eve and her role in The Fall. A second layer of patriarchal thought deems her, and by extension all women, more susceptible to the demonic than men – at least according to a couple of Dominican inquisitors from 1486. And women labeled as witches (the operative word being labeled), were executed in an effort to purify their village of Satanic influence.

The group most vulnerable to accusations of witchcraft was women between forty and sixty. That’s the same segment of society most likely to draw the black dot in The Lottery. In Puritan Massachusetts, accusations of witchcraft served to crush a particular class of women, insufficiently docile women who failed to fit into their assigned role of submissive helpmeet, those who spoke their minds or attempted to run their own affairs.[25]

So, why was Tessie Hutchinson stoned to death The Lottery? Tessie is precisely this type of woman. She shows up late and must weave her way through the crowd to reach her husband, who had been waiting quite some time for her to arrive. Tessie barks at her husband to “get up there,” when it’s his turn to select a slip of paper from the wooden box.[26] And she certainly isn’t docile when she shouts and yells, challenging the fairness of the lottery and by extension male authority.

Unfortunately for Tessie, much like the women of Puritan Massachusetts,[27] the other women in the village seem to have internalized the ominous lesson they were intended to learn, which is to keep their places in the established order.[28] For, it’s only women Jackson calls out by name as charging toward Tessie, stones in hand as the story ends.

_________

More Scapegoating in the Holocaust.

News from the Nuremberg trials, and revelations about the Holocaust were fresh in everyone’s mind. The horrific stories were more personal for Jackson than many Americans because, as the wife of a Jewish husband, she had first-hand experience with anti-Semitism. And though Jackson consistently refused to give a concise explanation of The Lottery, she did tell a friend that the story has to do with anti-Semitism.[29]

The scapegoating the Nazis employed on this colossal scale was an outcome of the ideological (mis)appropriation of Germany’s mythological heritage. The original concept was grounded in the idea that a proper nation, or Volk, requires a particular holistic unity. This totality must be comprised of a natural environment, a language and history rooted in a deep past and rural population, and the expression of that history in an indigenous mythology. The culture that emerged from this sentiment became radicalized, crystallizing as völkisch nationalism in the first third of the 20th century. [30] Anyone perceived as not fulfilling all aspects of this unity was painted as an enemy. And in an effort to “purify” the Volk, those deemed outsiders were targeted. Though Jews were considered the primary enemy, the Romani people and a number of other groups were also among those who collectively fulfilled the role of scapegoat.[31]

Jackson’s story echoes the reported experience of Holocaust survivors in several respects. Let’s start with the hard truth that children are not exempt in either scenario. Like the little girl who wore the red coat in the film Schindler’s List, Davy Hutchinson is at risk as much as everybody else. And that reality is about as disturbing and heart wrenching as it gets.

But more significant in terms of The Lottery’s narrative and its structure, is the fact that the ritual murder in The Lottery is alluded to, although not seen by the reader. Like the execution of survivors’ family members, the act of stoning in The Lottery isn’t witnessed directly. Consequently, in both instances, the focus becomes the very personal experience of the selection process, which needless to say determines between “death or reprieve.”[32] Which is why everyone sighs when little Davy’s paper was blank.

The Lottery’s narrative is the selection process. Jackson’s story is essentially a detailed description of the mechanics of the village’s lottery. And the following high points of that process sound an awful lot like the frequent selections that took place in concentration camps. Flanked by Mr. Graves and Mr. Martin, Mr. Summers declares the lottery open. “A sudden hush fell on the crowd as Mr. Summers cleared this throat and looked at the list. ‘All ready?’ he called.”[33] Once it was determined that this year’s victim would come from the Hutchinson household, each member of the family is called forth as they anxiously draw their individual lots.

This scenario is strikingly similar to the selection process Elie Weisel recounts in Night, the autobiographical account of his experience in both Auschwitz and Buchenwald:

Three SS officers surrounded the notorious Dr. Mengele, the very same who had received us in Birkenau. The Blockälteste [barracks leader] attempted a smile. He asked us: “Ready?” Yes, we were ready. So were the SS doctors. Dr. Mengele was holding a list: our numbers. He nodded to the Blockälteste: we can begin! As if this were a game… I had one thought: not to have my number taken down and not to show my left arm.[34]

There are enough accounts of the numerous and varied atrocities visited upon the people that comprise the Nazis’ collective scapegoat to fill a library, and they have. Yet, Weisel’s testimony to what occurred in the camps makes it clear that the most terrible word, the one feared more than any other, was selection.[35] Jackson’s villagers must feel the same way about the term lottery.

_________

The Lottery’s Deteriorating Ritual.

Jackson points out that the original box the villagers used for the lottery had been “lost long ago.” The fact that it was lost, rather than destroyed by termites for example or burned in a barn fire, suggests that over time the villagers have been turning away from the antiquated pagan beliefs this ritual is clearly grounded in. There was once a ritual salute. The lottery official no longer stands “just so.” He doesn’t sing the “tuneless chant” anymore.[36] And at one time there might have been something about him walking among the people… maybe. But these days, the lottery is something to be rushed through so everyone can “get home for noon dinner.”

This evolution of the village’s ritual reveals that the appearance of progress in society is an illusion. Letting go of antiquated pagan beliefs makes it appear that the people in the village have become more enlightened. But, they haven’t. As Jackson put it, “although the villagers had forgotten the ritual and lost the original black box, they still remembered to use stones.”[37] The point being, though the villagers have let go of most aspects of this pagan ritual they are not actually more civilized. The brutality at its core remains fully intact. And to drive that point home, what the tradition has evolved into, is simply an excuse for violence.

The most damning thing about this situation is that collectively, the townspeople could bring the lottery to an end. But, like the citizens of Salem who get drawn into the cycle of accusation rather than question church tradition, they don’t. They perpetuate this annual murder by teaching it to the younger generations. Someone not only helps Davy Hutchinson draw his slip of paper, they place stones in his little hand. And they do so simply for the sake of upholding tradition. We know this is the only motivation for continuing the lottery, because Old Man Warner’s only response to Mrs. Adams’ suggestion to give it up is nothing more substantial than, “there’s always been a lottery.”[38]

_________

In Conclusion

It’s no accident that Jackson chose stoning rather than a modern, mechanized method of ritual murder à la Nazi Germany, or the hanging employed in The Salem Witch Trials for that matter. She elected to use stoning, because pelting someone to death with rocks is as primitive as it gets. The symbolism is double-edged. Stoning not only speaks to the antiquity of the scapegoat tradition, most importantly it’s a statement about the current state of humanity. Jackson’s choice of stoning is her not too subtle way of saying we’re just as savage as we ever were.

Jackson paints a pretty dismal picture. She seems to be saying that these villagers (and by that she means the whole of humankind) will never be free of their primitive nature. At least, not until enough of them have been affected adversely enough by the horror of their tradition that they reject it and, as Mrs. Adams implies, destroy the box altogether. Or they fashion a new box, one that reflects their current social conditions and sustains them rather than pitting them against each other.[39] Until that happens, Tessie Hutchinson may be the only loser, but no one is a winner.

That’s my take on Shirley Jackson’s The Lottery – what’s yours?

Check out this Discussion Guide to get you started.

#post-war social commentary #banned books #witch trials #witchcraft #Puritan #symbol #holocaust

Endnotes:

[1] Jackson, Shirley. “Biography of a Story.” Shirley Jackson: Novels & Stories. Edited by Joyce Carol Oates. (New York: Library of America, 2010), 787.

[2] Gahr, Elton. “Criticism of “The Lottery” by Shirley Jackson: Reactions upon the Initial Publication & Today.” Bright Hub Education.com August 31, 2011; Jackson, “Biography of a Story;” Cohen, Gustavo Vargas. Shirley Jackson’s Legacy: A Critical Commentary on the Literary Reception. Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul. July 2012, 17.

[3] Jackson, “Biography of a Story;” Cohen Shirley Jackson’s Legacy, 17.

[4] Jackson, “Biography of a Story,” 797, 799, 797.

[5] ACLU-or.org Oregon Library School Challenges 1979-July 2015.

[6] Brown, Jean E., Ed. SLATE on Intellectual Freedom. (Urbana Ill: National Council of Teachers of English,1994), 24.

[7] Brown, Bill, et al. “The Censoring of “The Lottery.’” The English Journal. Feb., 1986, Vol. 75, No. 2.

[8] Jackson, Shirley. “Biography of a Story.” Shirley Jackson: Novels & Stories. Edited by Joyce Carol Oates. (New York: Library of America, 2010), 787; Franklin, Ruth. Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life. (New York: W.W. Norton & Co, 2016), 222.

[9] Heller, Zoe. “The Haunted Mind of Shirley Jackson.” The New Yorker. October 17, 2016; Oppenheimer, Judy. “The Haunting of Shirley Jackson.” The New York Times. July 3, 1988.

[10] Franklin, Ruth. Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life. (New York: W.W. Norton & Co, 2016), 221, 217, 234; Hyman, Stanley Edgar. “Preface,” The Magic of Shirley Jackson, by Shirley Jackson (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1965), ix.

[11] Franklin, Ruth. “The Lottery Letters.” The New Yorker. June 25, 2013.

[12] Bogert, Edna. “Censorship and ‘The Lottery.’” The English Journal. Vol. 74, No. 1 (Jan., 1985), 47; Yarmove, Jay A. “Jackson’s ‘The Lottery.’” The Explicator. Vol. 52, Issue 4. *Summer, 1994), 242-245.

[13] Hyman The Magic of Shirley Jackson, ix.

[14] Nebeker, Helen E. “’The Lottery’ Symbolic Tour de Force.” American Literature. (Mar. 1974, Vol. 46. No. 1), 100-102

[15] Nebeker, “’The Lottery’ Symbolic Tour de Force.” 101-102.

[16] Nebeker “’The Lottery’ Symbolic Tour de Force.” 103; Jackson, Shirley. “The Lottery.” The New Yorker. June 26, 1948.

[17] Cooper, Howard. “Some Thoughts on ‘Scapegoating’ and its origins in Leviticus 16.” European Judaism: A Journal for the New Europe. Vol. 41, No. 2 (Autumn 2008).

[18] Frazer, James George. The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion. (New York: MacMIllan Company, 1925), 579; martin, John. An Account of the Natives of the Tonga Islands. (London: John Murray, 1817), 229.

[19] Frazer The Golden Bough, 575.

[20] Jackson The Lottery.

[21] Oehlschlaeger, Fritz. “The Stoning of Mistress Hutchinson: Meaning and Context in ‘The Lottery.’” Essays in Literature. Vol. 15, Issue 2 (Fall 1988), 263.

[22] Oehlschlaeger, “The Stoning of Mistress Hutchinson,” 262-263.

[23] Jackson The Lottery.

[24] Whittier, Gayle. “’The Lottery’ as Misogynist Parable.” Women’s Studies. Vol. 18. (1991), 357.

[25] Radford-Ruether, Rosemary. Sexism and God-Talk. (Boston: Beacon Press, 1993), 171-172.

[26] Jackson The Lottery.

[27] In her book Sexism and God-talk, Rosemary Radford-Ruether argues that the witchcraft persecutions in Puritan Massachusetts began to decline by 1700 at least in part because they had served their purpose and were no longer necessary to enforce the patriarchal order.

[28] Radford-Ruether Sexism and God-Talk, 171-172.

[29] Franklin Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life, 234.

[30] Von Schnurbein, Stefanie. Norse Revival: Transformations of Germanic Neopaganism. (Boston: Brill, 2016), 17.

[31] “Defining the Enemy.” Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

[32] Weisel, Elie. Night. (New York: Hill and Wang, 2006), 70.

[33] Jackson The Lottery.

[34] Weisel Night, 71-72.

[35] Weisel Night, 70; Dwork, Debórah, and Robert Jan Van Pelt. Auschwitz. (New York: W. W. Norton, 2008), 353.

[36] Jackson The Lottery.

[37] Jackson The Lottery.

[38] Jackson, The Lottery; Robinson, Michael. “Shirley Jackson’s ‘The Lottery’ and Holocaust Literature.” Humanities. 8.1 (2019).

[39] Nebeker, “‘The Lottery’ Symbolic Tour de Force.” 107.

Images:

1 Cover. Jackson, Shirley. The Lottery. (New York: Popular Library, 1976). Image is supplied by Amazon.com via Internet Speculative Fiction Data Base. http://www.isfdb.org/cgi-bin/pl.cgi?413754 . The original image has been cropped. It is utilized under a Creative Commons license. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/legalcode.

2 New England Village. Photo by Yuval Zukerman on Unsplash

3 Mountain Goat. Photo by Maria Teneva on Unsplash

4 Hale, John, and John Higginson. A modest enquiry into the nature of witchcraft, and how persons guilty of that crime may be convicted: and the means used for their discovery discussed, both negatively and affimatively, according to Scripture and experience. By John Hale, Pastor of the Church of Christ in Beverley, anno domini 1697. [Six lines of Scripture texts]. Printed by B. Green, and J. Allen, for Benjamin Eliot under the town house, 1702. Eighteenth Century Collections Online, link.gale.com/apps/doc/CB0127095065/ ECCO?u=sain79627&sid=bookmark-ECCO&xid=f70c042b&pg=1. Accessed 10 Jan. 2022.

5 Auschwitz Concentration Camp. Photo via www.auschwitz.org

6 Stonehenge. Public Domain via www.goodfreephotos.com

https://www.goodfreephotos.com/albums/england/other-england/stonehenge-under-the-sunset-skies.jpg

FYI:

This Book is Banned participates in the Amazon.com affiliate program, where we earn a small commission by linking to books (but the price remains the same to you). This allows us to remain free, and ad free. [Our privacy policy]

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!