L

L

uck of the Irish. We hear this expression most often around St. Patrick’s Day. And, it’s usually associated with leprechauns – the magical, smiling kind, like the one on boxes of Lucky Charms cereal.

So, when someone is said to have the Luck of the Irish, it’s understood to mean they have an unnatural tendency toward good fortune. However… like a lot of other sayings, its original use tells a very different tale.

For starters, the leprechauns of Irish folklore are tricksy, mischievous little buggers (unlike the “wee person” represented by the General Mills company). According to Irish lore, they do indeed know the whereabouts of hidden treasure, but they can also be “bitterly malicious.”[1] So, even successful encounters with these supernatural beings are nothing short of treacherous.

Our “Lucky Charms” view of leprechauns is void of history and genuine Irish culture. Which is also the case with our current understanding of the expression “Luck of the Irish.”

A decided unlucky history.

As Irish satirist Jonathan Swift is credited with pointing out, historically speaking the luck of the Irish people has been positively abysmal.[2] Ireland was subordinated to English control beginning with Henry VIII, a conquest that began with a Norman invasion and was finally completed during the reigns of Elizabeth 1 and James 1.

Laws designed to fragment the estates of Irish landowners were put in place. And, like every successful colonizer, crown authorities employed brutal methods to squash resistance and exploit Ireland’s resources.[3]

An Gorta Mór

After centuries of such oppression, Ireland experienced an Gorta Mór “The Great Hunger,” known to most of us as the “potato famine.”[4] A mid-famine sentiment regarding this devastating calamity is that “God sent the blight, but the English made the famine.”[5]

More than one historian has characterized Britain’s handling of the situation as a convenient opportunity to finally crush Irish refusal to toe the British line, which famously included an attachment to Catholicism.[6]

Whether exacerbated by socio-political motives or not, in a country of eight million, the famine resulted in the death of more than one million people.[7] And nearly two million departed Ireland, as emigration became the last refuge of a desperate people who saw it as their only hope of survival.[8]

A significant proportion of those emigrating made their way to the United States. And the trip across the Atlantic was no picnic. For many, the journey took place on what came to be known as “coffin ships,” so-titled because the mortality rate on these overcrowded ships was 30% or higher on some ships. This catastrophic mortality rate was caused by overcrowding, unsanitary conditions, malnutrition, and disease, a combination that ensured death was a constant presence.[9]

No Irish Need Apply

And when they got to America, the Irish refugees who survived their traumatic journey were frequently met with job listings and signs in places of business indicating “No Irish need apply.”[10] This attitude was fueled by images in media characterizing the Irish as uncivilized, depicting them with simian or pig-like features.[11]

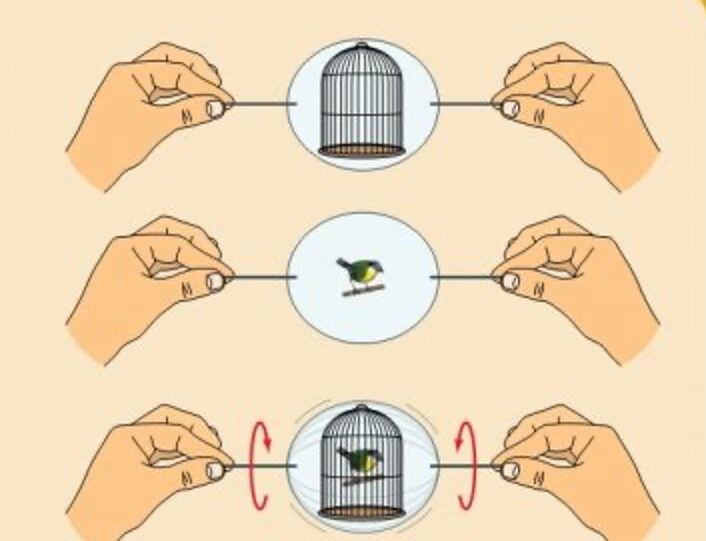

What’s a recently landed son of Erin to do? Well… the famine that drove so many Irish people from the nation of their birth happened to coincide with the California Gold Rush. Opportunity finally seemed to be knocking.

But availing themselves to this fortuitous prospect would entail another difficult journey for Irish immigrants, one that would require them to sail around the tip of South America, and would take four or five months to complete. If they could scrape together the funds for passage, that is.

An alternative to this lengthy sojourn was to take a shorter voyage to Panama, trek for a week through malarial territory using canoes and mules (risking not only malaria but cholera as well), then take another ship from the west coast of Panama to California.

Or they could travel over land, by way of the harsh western deserts and mountains, through (often hostile) Native American territory.[12]

Irish gold miners

However they got to California, these Irish gold miners clearly had a will to succeed and a drive to never give up. And that’s exactly what you need if you’re going to be digging and panning for gold.

This is not to say that other immigrants who made the same journey lacked a similar work ethic. But, the timing of the famine drove enough Irish immigrants to the gold rush that an inordinately high percentage of miners were Irish.

So, it only makes sense that a significant number of successful miners would be Irish. And, that’s precisely what happened. The most famous and successful miners were indeed of Irish descent.[13]

That’s the context the expression “Luck of the Irish” emerged from.

But as historian Edward T. O’Donnell points out, the phrase “carried with it a tone of derision as if to say, only by sheer luck, as opposed to brains, could these fools succeed.”[14] Which is nothing less than absurd given the work ethic required to be a successful gold miner, to say nothing of the grit and determination it took for these Irish immigrants to make it to California to begin with.

In Conclusion

Historically speaking the Irish were anything but lucky. What kind of luck gives rise to roughly centuries of invasion, colonization, exploitation, starvation and mass emigration? Certainly not the kind we associate with the phrase “Luck of the Irish” on St. Patrick’s Day.

Not to mention the fact that the expression was originally intended as mockery, born of a certain jealousy, a sense of victimhood based in a lack of regard for Irish immigrants and what they had endured to make their way to America and become successful.

If you’ve ever had your hard work or years of preparation dismissed out of hand, then you have the Luck of the Irish as the expression was originally intended. If you, or someone you know has left their home country due to dire circumstances there, only to be despised and derided in the country they emigrate to in the hopes of a better life, they have the Luck of the Irish too.

Hopefully, knowing the original intent of this expression will give us pause as we throw it around next St. Patrick’s Day. Hopefully, knowing its original intent will remind us to acknowledge the hard work of those around us. And, hopefully… just maybe, it’ll help us recognize that others (especially those newly-arrived to the United States) might have overcome tremendous adversity in order to achieve even a modicum of success.

Share This Post, Choose a Platform!

Endnotes:

[1] Lady Wilde. Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms, and Superstitions of Ireland. Vol. 1. Boston: Tickner & Co., 1887.Pg 103.

[2] Lee, Peter. “Fancy some Irish luck? These Irish sayings about luck are for you.” Irish Central. https://www.irishcentral.com/culture/craic/fancy-some-irish-luck-these-irish-sayings-about-luck-are-for-you

[3] Miller, Kerby A. Emigrants and Exiles: Ireland and the Irish Exodus to North America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985. Pp 16-25.

Lennon, Colm. Sixteenth Century Ireland – The Incomplete Conquest. Dublin: St. Martin’s Press,1995.

Canny, Nicholas P. The Elizabethan Conquest of Ireland: A Pattern Established, 1565–76. Sussex: Harvester Press Ltd, 1976.

[4] O’Neill, Joseph. The Irish Potato Famine. Edina, Minn.: ABDO Publishing Co., 2009. Pg 7.

[5] Bloy, Marjie. “The Irish Famine: 1845-9.” The Victorian Web. https://victorianweb.org/history/famine.html

[6] Coogan, Tim Pat. The Famine Plot: England’s Role in Ireland’s Greatest Tragedy. New York: Palgrave McMillan, 2012.

Kinealy, Christine. This Great Calamity: The Irish Famine 1845-52. Boulder, Colorado: Roberts Rinehart Publishers, 1995.

O’Dowd, Niall. “Was the Irish Famine genocide by the British?” IrishCentral.com Aug 20, 2018. https://www.irishcentral.com/news/irish-famine-genocide-british

[7] Kinealy, Christine. This Great Calamity: The Irish Famine 1845-52. Boulder, Colorado: Roberts Rinehart Publishers, 1995. Pg 251.

[8] Kinealy, Christine. This Great Calamity: The Irish Famine 1845-52. Boulder, Colorado: Roberts Rinehart Publishers, 1995. Pg 299.

O’Leary, Rachel. “Coffin Ships.” Irish Famine Exhibition. Dublin Museum. January 22, 2025.

[9] O’Leary, Rachel. “Coffin Ships.” Irish Famine Exhibition. Dublin Museum. January 22, 2025.

“Coffin ships: death and pestilence on the Atlantic.” Irish Genealogy Toolkit. https://www.irish-genealogy-toolkit.com/coffin-ships.html

[10] Bulik, Mark. “1854: No Irish Need Apply.” September 8, 2015. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/08/insider/1854-no-irish-need-apply.html

[11] Forker, Martin. “The use of the ‘cartoonist’s armoury’ in manipulating public opinion: anti-Irish imagery in 19th century British and American periodicals.” Journal of Irish Studies, 2012. Vol. 27 (2012) Pg. 59.

[12] Nolan, Philip. “How the Irish mined the gold rush.” Irish Daily Mail. August 10, 2019. https://www.pressreader.com/ireland/irish-daily-mail/20190810/282183652681471

[13] O’Donnell, Edward T. 1001 things everyone should know about Irish-American history. New York: Grammercy Books, 2002. Pg 226.

[14] O’Donnell, Edward T. 1001 things everyone should know about Irish-American history. New York: Grammercy Books, 2002. Pg 226.

Images:

Irish Clover: Photo by Frames For Your Heart on Unsplash

Portrait of Jonathan Swift: Charles Jervas (1718), National Gallery of Ireland. Public Domain.

An Gorta Mór : “Bridget O’Donnell.” Illustrated London News, December 22, 1849 – public domain.

No Irish Need Apply: Bulik, Mark. “1854: No Irish Need Apply.” September 8, 2015. The New York Times.

Irish Gold Miner: ‘Ireland at the Diggings’: The Irish of the California Gold Rush Celebrate Home, 1853.” Irish in the American Civil War.

Celtic Knot: The Irish Road Trip.com

W

W

L

L

Y

Y