If You’re Not Engaging a Book’s Symbolic Language, You Aren’t Really Reading It.

A

A

novel’s symbolic language carries a message beyond simply what happens in the plot. But like luggage, it has to be unpacked.

Reading literature is more than being swept along by the charm of the characters, anticipation for the next shocking twist, or the thrill of the events on display. But it can be tricky.

After all, as Hermann Hesse points out, the same language employed by poets and novelists is also used in school and business, to dispatch telegrams, and conduct lawsuits. It’s easy to get stuck reading “naïvely,” to assume that a book is to be judged according to its substance. “Just as a loaf of bread is there to be eaten and a bed to be slept in.” [1]

A book’s content, however, is not the only consideration. As pointed out in a previous article, there’s more to a novel than surface narrative. One of the layers that gives meaning to a novel’s narrative is the symbolic language imbedded in it. So, if you’re not engaging a book’s symbolic language, you aren’t really reading it.

As Virginia Woof advised, the numerous chapters of a novel “are an attempt to make something as formed and controlled as a building: but words are more impalpable than bricks; reading is a longer and more complicated process than seeing.”[2] So, no matter how enjoyable a book may be, if you’re just reading for plot and an entertaining story, you aren’t even getting half of what it has to offer. So, here are a few forms of symbolic language to be on the look-out for the next time you pick up a book.

_________

Symbol:

What is it and how does it work?

Strictly speaking, symbol is defined as something that represents something else by association. But, be sure not to confuse symbol with sign. Symbol differs from sign because signs are straightforward. For instance, 👈 means turn left no matter where you are in the world. Symbols, on the other hand have more than one layer, with the literal meaning “pointing the way” to a second, fuller meaning. So, in order to really read a book, you need to unpack this second layer. Take the sea monsters in Homer’s Odyssey, Scylla and Charybdis, for instance.

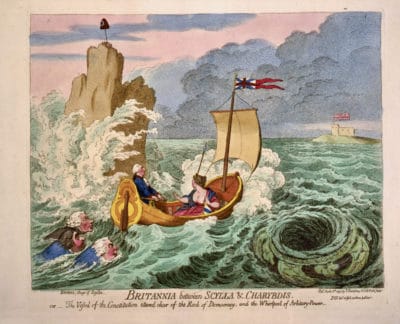

In an earlier post, we talked about the fact that literature isn’t written just for our entertainment, that the story is consistently a vehicle for a larger point. And, so it is with the Odyssey. On its face, Homer’s epic is an adventure story about Odysseus, king of Ithaca, and his ten-year journey home after the Trojan War. The Odyssey is chockfull of fantastic creatures, such as the giant Cyclops, and Sirens who lure men to their doom with song, not to mention the six-headed sea monster Scylla and the whirlpool creature Charybdis already mentioned. Now, Scylla and Charybdis live in close proximity to each other, making it nearly impossible to safely navigate between them. If you steer clear of Scylla’s cave, you get sucked in by Charybdis. On the other hand, if you maneuver away from Charybdis, man-eating Scylla jumps out of its cave and… well, you get the idea. So, what’s a Greek sailor to do?

Odysseus’ dilemma is precisely the point. The literal reading of these two sea monsters “points us” to the realization that this is a situation where there is no good choice. And that is what Scylla and Charybdis symbolizes, the impossible choice we’ve all had to make at one time or another in our lives. While Scylla and Charybdis are a fantastic pair in and of themselves, engaging the symbol, understanding the paired monsters’ deeper meaning gives Homer’s Odyssey continued relevance. Odysseus’ journey gives us insight into our own.

The important thing to remember about symbolic language is that the advent of the written word changed human storytelling. We no longer automatically engage with symbolic language like we did when we lived in an oral culture. This is not to say the ability to decipher symbol is lost forever. But these days it takes a conscious effort to do so, to do more than simply process text.

_________

Myth:

What is it and how does it work?

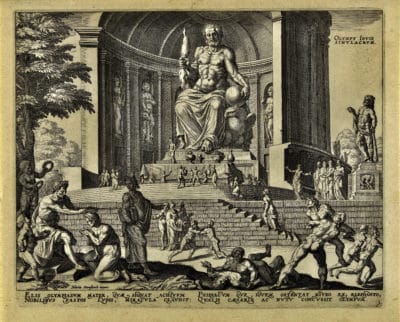

The next form of symbolic language we’re going to take a look at is myth, and the first thing we need to do is establish what myth is not. Myth is not folklore, legend, or tall tales, though it is often confused with all of them. If myth isn’t any of these, then what is it? Myth is essentially symbol in narrative form.[3] This form of symbolic language relates how a reality came into existence, be it the whole of creation, a specific species, or a particular human behavior.[4] For example, you’re probably familiar with Prometheus. His is the myth about how human beings acquired the ability to make fire. Though Zeus was withholding fire from humans, Prometheus stole it and gave it to mankind. Needless to say, he was punished for his trouble.[5]

While it’s important to recognize myth when we see it, the discussion at hand leads us to another important factor in the evolution of human storytelling. The recitation of myth that was prevalent in traditional societies has been replaced by the reading of prose narrative, especially the novel. In the context of symbolic language, this turn of events is significant because mythological themes and characters are frequently reflected in modern day novels. So, it helps to “know your myths,” to at least have a passing acquaintance with the classic catalog.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is a perfect example of the convergence of myth and literature. In fact, the full title of Shelley’s work is Frankenstein; or the Modern Prometheus. While the plot does indeed revolve around a “monster,” there is much more to it than that. The parallel drawn to a myth about forbidden technology stolen from the gods transforms Shelley’s work from a sleep-over worthy horror story to a narrative that speaks to the ethics and morality of scientific experimentation. And we haven’t even gotten to the consequences of “playing God” yet. Clearly, engaging Frankenstein’s symbolic language results in a more profound reading of Shelley’s work, one more pertinent than ever.

_________

Allegory:

What is it and how does it work?

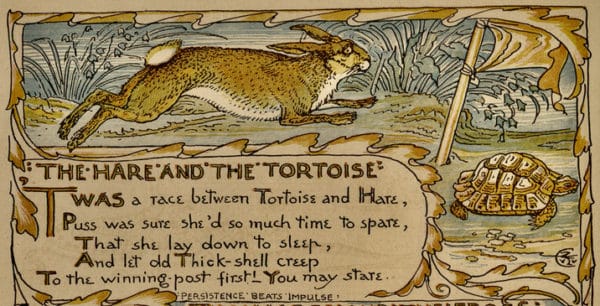

Like myth, allegory is both representational and in narrative form. While myth is a means of understanding the world and how it came to be, allegory’s purpose is rhetorical in nature. By employing allegory, the author transforms a phenomenon they wish to address into figural narrative.[6] This of course begs the question, if the author transforms the target of their commentary, how does the reader know what the actual subject is? For starters, the novel’s structure is itself a guiding principle. And ultimately, the author’s message emerges from the details of the text.

Allegory functions on a this equals that formula, and unlike symbol, the secondary meaning is directly accessible. In short, allegory functions rather like a cryptic key. And, knowing at least a little about the author is beneficial. An awareness of the political environment and significant events that occurred during the period the work was written, also helps crack the code.

George Orwell’s commentary on Soviet Russia, Animal Farm, is a prime example of allegory. It is highly unlikely that a reader would mistake this book as actually being about talking farm animals in conflict, so what is it really about? The political environment of the period, combined with the character traits of the work’s personified animals, enable the reader to understand the novella as the criticism it is. And Orwell’s choice to convey his political warning through fiction rather than a straightforward political essay conforms to the principle that narrative is the most effective way to circulate critical information. Case in point, a story about authoritarian pigs definitely holds our attention better than straightforward political commentary.

Allegory’s defining this equals that formula is reflected in the direct correlation between Orwell’s farm animals and specific Russian political figures. Old Major, the oldest boar on the farm, embodies Karl Marx. A younger pig named Snowball, represents Leon Trotsky, Vladimir Lenin’s second-in-command. And Joseph Stalin is clearly recognizable as the ruthless boar named Napoleon.[7] In addition to the animal-politician overlay, frequent use of the term “comrades,” makes the theme difficult to miss.[8]

_________

Metaphor:

What is it and how does it work?

The last symbolic device we’re going to consider is metaphor. Like myth and folktale, metaphor and simile are often confused. Though they seem similar, the difference is significant. To help clarify between the two devices, let’s take a look the following excerpt from Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, which includes both. While setting a book-filled house aflame, the fire chief directs Bradbury’s protagonist to:

![]() Sit down, Montag. Watch. Delicately, like the petals of a flower. Light the first page, light the second page. Each becomes a black butterfly. Beautiful, eh?

Sit down, Montag. Watch. Delicately, like the petals of a flower. Light the first page, light the second page. Each becomes a black butterfly. Beautiful, eh? ![]() [9]

[9]

The way simile works is quite simple. It directly states that one thing is like another thing, that this is like that. But simile is descriptive and nothing more. And as much as simile indicates likeness, it also acknowledges difference. If one thing is like another thing, then these two things cannot be identical. Bradbury’s simile exemplifies this formula, suggesting that the pages of a book Montag and Beatty just set on fire are like the petals of a flower.

Metaphor, on the other hand, functions on a double intentionality much like symbol does. But they too are very different from one another. The distinguishing factor between metaphor and symbol is that rather than having a primary layer that points the way to a second meaning (as in symbol), the concepts at work in metaphor overlap (rather like a Venn diagram) and a new entity is born of the common characteristics.

Bearing this in mind, let’s return to the Bradbury quote. In the metaphor he employs, each page of the burning book becomes a black butterfly, each page is a black butterfly. Clearly, a charred page being a black butterfly is a much more powerful image than if the page just looked like a butterfly. But the reason metaphor is more potent than the other devices we have talked about, is because of the way our brain processes them.

Through what is known as “cross-domain mapping,” information stored in our brain about one concept (in this case charred paper) crosses from its original domain to a different area in the brain, where information about the second element of the metaphor (in this case butterflies) resides.[10] This overlap of domains allows us to utilize what we know about butterflies to think about the charred pages Bradbury refers to.Tapping into our “butterfly information,” we envision each burned page transform (like caterpillars do), emerging from its chrysalis/book, in its new delicate form to waft away on the air. As a result of cross-domain mapping, we relate to metaphor in a way that doesn’t happen with simile. We engage the image invoked rather than merely visualize it.

_________

Theme:

What is it and how should we think about it?

Technically speaking, a theme is not a form of symbolic language. Theme is, however, a literary device that informs the interpretation of a novel, short story, or poem.

Most of us have been taught that a literary theme is a work’s main topic, what the piece is about. Theme has also been defined as a book’s underlying message, or what the work means. And, theme has been boiled down to being the moral of the story.

Many educators consider theme to be one of the most complicated aspects of fiction to discuss, because (as we’ve seen) there’s no simple definition. But there’s one thing these similar but varied renditions have in common – they’re all statements. But themes don’t have to be.

Formulating themes as statements results in restrictive thinking. Seeing theme as a question, on the other hand, sets up an open-ended thought process, inducing us to ponder larger considerations. For example, noting gender as a theme in The Scarlet Letter ends the discussion… “Hawthorne’s theme is ‘the Puritans were patriarchal tyrants.’”

But considering theme as a question sparks larger thinking, like “what prompted Hawthorne to choose gender as a means of calling out Puritan theocratic tyranny?” which leads to the inevitable question “is anything like that happening now?”

The inimitable Chekhov said it best:

![]() It seems to me that the writer should not try to solve such questions as those of God, pessimism, etc. His business is but to describe those who have been speaking or thinking about God and pessimism, how and under what circumstances. The artist should be not the judge of his characters and their conversations, but only an unbiased observer.

It seems to me that the writer should not try to solve such questions as those of God, pessimism, etc. His business is but to describe those who have been speaking or thinking about God and pessimism, how and under what circumstances. The artist should be not the judge of his characters and their conversations, but only an unbiased observer.

You are right in demanding that an artist approach his work consciously, but you are confusing two concepts: the solution of a problem and the correct formulation of a problem. Only the second is required of the artist. ![]() [11]

[11]

Analyzing themes in this manner facilitates a greater understanding of the work itself. But more importantly, the reader can utilize insights they’ve gained to grasp a better sense of the world they live in and their place in it.

That’s what makes stories “true,” even when they’re fiction. It’s what also keeps literature relevant, no matter when it was written.[12]

As you can see by the literary devices we have examined, a novel’s symbolic language does indeed carry a message beyond merely what happens in the plot. And more often than not, it’s hauling a significant load. So, I’ll wrap up this excursion into symbolic language where I began, with the admonition that if you are not engaging a book’s symbolic language, then you aren’t really reading it.

But now you know what is meant by “symbolic language,” and you have a few tools to unpack it with.

_____________________________________

Be sure to check out these companion articles:

We May Read for Enjoyment,

But Literature Isn’t Written Just to Entertain Us.

Novels are Like a Layer Cake,

Be Sure to Get Every Bite.

Literary Devices:

Literary Devices: The Author’s Toolbox

#literary criticism #The Art of Reading #symbolic language

#critical thinking #literary devices #literacy

Endnotes:

[1] Hesse, Hermann. “Language.” and “On Reading Books.” in My Belief: Essays on Life and Art. Edited by Theodore Ziolkowski. Translated by Denver Lindley. (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1974), 26, 101-102.

[2] Woolf, Virginia. “How Should One Read a Book?” The Common Reader, Second Series. (1935). (Gutenberg of Australia eBook. 0301251h.html).

[3] Ricoeur, Paul. Symbolism of Evil. (Boston: Beacon, 1978), 18.

[4] Eliade, Mircea. Myth and Reality. Translated by Willard R. Trask. (Prospect Heights, Ill: Waveland Press, Inc., 1963), 5.

[5] Hansen, William. Classical Mythology: A Guide to the Mythical World of the Greeks and Romans. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 48.

[6] Johnson, Gary. The Vitality of Allegory: Figural Narrative in Modern and Contemporary Fiction. (Columbia: Ohio State University Press, 2012), 8.

[7] Orwell, George. Animal Farm. (New York: Penguin, 1996), vi.

[8] Johnson, 25.

[9] Bradbury, Ray. Fahrenheit 451. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2013), 72.

[10] Lakoff, George. “Contemporary theory of metaphor.” Metaphor and Thought (2nd edition). Edited by Andrew Ortony. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 203.

[11] “Learning from Chekhov.” In Writers on Writing. Edited by Robert Pack, jay Parini. Hanover: University Press of New England, 1991. Pg 229.

[12] Kramer, Lindsay. “A Guide to Themes in Writing and Literature.” June 29, 2022. Grammarlyblog.

Wrede, Patricia C. “The Question of Theme.”

Bushnell, J. T. “What is a Theme in Literature?” The Oregon State Guide to Literary Terms.

“Theme.” Literary Devices: Definition and Examples of Literary Terms.

Images:

[1] Introductory Photo. Photo by Koala on Unsplash . https://unsplash.com/photos/P0NuBF6nA7A?

[2] Scylla and Charybdis. Gillray, James, Artist. Britannia between Scylla & Charybdis. or – The vessel of the Constitution steered clear of the Rock of Democracy, and the Whirlpool of Arbitrary-Power / Js. Gy. desn. et fect. pro bono publico. Great Britain, 1793. [London: Pub. by H. Humphrey, April 8th] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/94509857/

[3] Standbeeld van Zeus in Olympia. Anonymous, after Philips Galle, after Maarten van Heemskerck, 1638. Public Domain via Rijksmuseum.nl http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.114919

[4] Aesop, Walter Crane, Elizabeth Robins Pennell Collection, and Oliver Wendell Holmes Collection. The baby’s own Aesop: being the fables condensed in rhyme, with portable morals pictorially pointed. London ; New York: George Routledge & Sons, 1887. Pdf. https://www.loc.gov/item/04017584/.

[5] Black Butterfly. Photo by Millie Greaves on Unsplash.

https://unsplash.com/photos/GKdeGSTlayM?

[6] Crystal Ball. Photo by Alvin Lenin on Unsplash

https://unsplash.com/photos/2ta8OjluZuI?

FYI:

This Book is Banned participates in the Amazon.com affiliate program, where we earn a small commission by linking to books (but the price remains the same to you). This allows us to remain free, and ad free. [Our privacy policy]