F

F

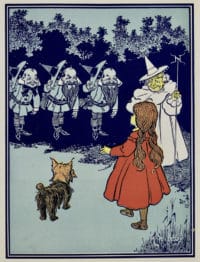

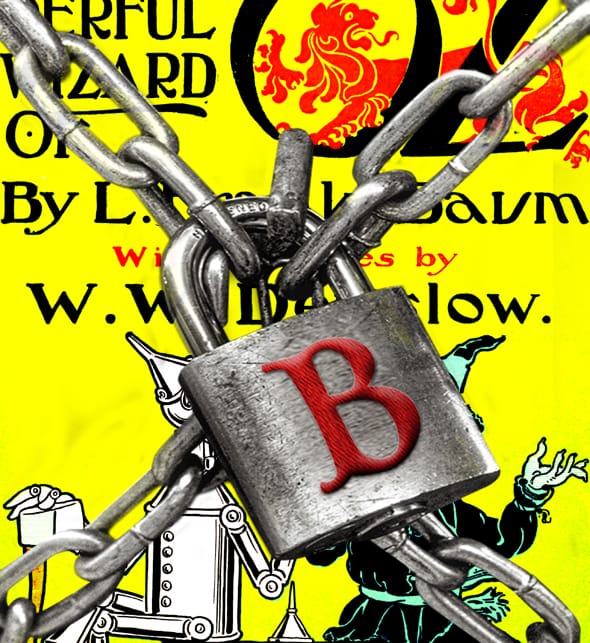

Frank Baum set out to write a “modernized fairy tale” for the children of his day.[1] According to the Library of Congress, he did more than simply accomplish his goal. He ended up producing “America’s greatest and best-loved homegrown fairytale.”[2] So, it seems inconceivable that certain parents and teachers have been trying to ban The Wonderful Wizard of Oz since its publication in 1900.[3]

Well, they have. In 1928, public libraries across the country pulled the books from their shelves.[4] Why was The Wonderful Wizard of Oz banned? Reasons range from Baum’s “wonder tale” being “untrue to life” (isn’t that the point of a wonder tale), to the use of witchcraft, to its portrayal of a strong female protagonist.[5]

One of the most publicized cases against The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, however, occurred in 1986. A group of Fundamentalist Christian families from Tennessee got together and tried to have the book removed from the public school syllabus. Baum’s work was among a number of books that the families felt promoted “occultism, secular humanism, evolution, disobedience to parents, pacifism, and feminism.”[6]

The families specifically disapproved of Baum’s characterization of some witches as good, because as we all know witches are in fact bad, very, very bad. One mother worried that reading this book would cause her children to be “seduced into godless supernaturalism.”[7] The federal judge who presided over the case ruled that children of the parents who brought the suit could be excused from lessons about Baum’s book. But the families weren’t happy with such a limited outcome. They wanted to make sure that no students were reading The Wonderful Wizard of Oz in class. So, they appealed the judge’s decision to the United States Supreme Court. Thankfully, the justices refused to hear the case.[8]

Objections to Baum’s book are clearly based on a literal, and therefore anemic reading of Baum’s book, a level Hermann Hesse describes as reading “naïvely.”[9] If these families had considered anything about who L. Frank Baum was or when he was writing, they would have seen a slice of American history reflected in the work’s imagery. And if they’d been familiar with the notion of symbolic language, they would have realized that literal magic is not what Baum was talking about.

They would’ve discovered what makes The Wonderful Wizard of Oz so special. There’s more to Baum’s book than “girl power!” and “pointy-hatted witches are a really a thing.” There is a deeper meaning behind The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. The fantastic creatures that inhabit Oz are not just the trappings of a wonder tale. The Scarecrow, Tin Woodman, and Cowardly Lion are more than just new friends Dorothy makes along the way. And the trials they endure serve a purpose other than simple adventure. Baum’s philosophy for writing successful children’s stories points the way to understanding why The Wonderful Wizard of Oz is more than just a fun story. __________

Oz, a land Betwixt & Between.

According to Baum, “Many authors have an idea that to write a story about children is to write a children’s story. No notion could be more erroneous. Perhaps one out of a hundred alleged children’s stories possess elements of interest to the real child – but that is a liberal estimate.”[10] Maybe so. But whether his comment is statistically accurate or not, the following excerpt from Baum’s article What Children Want reveals his philosophy for writing (undeniably successful) children’s books:

It is said that a child learns more during the first five years of its life than in the succeeding fifty years. This may well be true, for all the marvels of life and the wonders of the universe are brought to its notice and registered upon the sensitive film of its mind in those years when it first begins to understand it is a component part of mighty creation. The very realization of existence is sufficient to set every childish nerve tingling with excitement, and when the mind has absorbed the astonishing circumstances of its environment there comes a time when comprehension pauses, to resume more deliberately the practical details of worldly experience. Thus the amazed child, wild-eyed, eager, nervous and filled with unalloyed vigor, steps upon the threshold of real life… Positively the child cannot be satisfied with inanities in its story books. It craves marvels – fairy tales, adventures, surprising and unreal occurrences; gorgeousness, color and kaleidoscopic succession of inspiring incident.[11]

In short, children’s books should engage their imaginations and promote wonder, like when a little one “tak[es] its first peep at the world’s wonderland.”[12] More importantly, Baum’s article gives us insight into why The Land of Oz evokes a sense of wonder and fascination, and engages his intended audience the way it clearly has. It isn’t just because Baum was an excellent storyteller. Oz is chockful of marvels, adventure, and dreamlike happenings because it is a liminal realm, one that’s “betwixt & between.”[13] The Land of Oz is betwixt & between because the structure of Baum’s work parallels the pattern within rites of passage.

What are rites of passage? Think Bar Mitzvahs, and weddings. Rites of passage bring about the transition from one “mode of being” to another.[14] For example, the shift from childhood to adulthood in the case of bar mitzvahs. Or the switch from the mode of being single to the state of being married that a wedding produces. Dorothy’s transition, however, is from the mode when a child lacks the understanding that they’re “a component part of mighty creation,” to the point when they deliberately embrace “the practical details of worldly experience.”[15] This transformation ultimately prepares children to “step upon the threshold of real life.”[16] (Keep in mind that the Dorothy Gage in Baum’s book is significantly younger than Judy Garland’s portrayal in the 1939 film.)

__

How Do Rites of Passage Work?

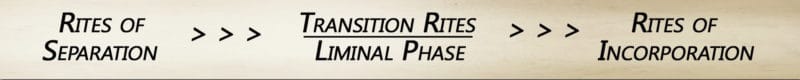

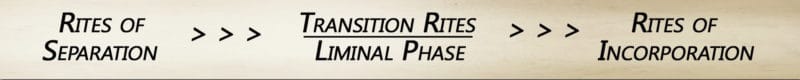

Rites of Passage contain the following three sub-categories:

.

The first and last stages are self-explanatory. They detach the subject from their old place in society, and return them, inwardly transformed, to their new station in life. As to the middle phase, the term “liminal” comes from limen, the Latin for “threshold,” indicating the “transition between.”[17]

Though all three stages are present in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, Baum primarily focuses on the liminal phase. Unlike the movie, all we get in the book is mere snippets of Kansas, just enough to anchor the story and show how fantastic Oz is by comparison. Oz’s fanciful nature is significant because liminality is by definition an unpredictable state. It’s a “realm of pure possibility,” between the two stable points (signified here by Kansas) that bookend the progression from one mode of being to another.[18] __________

What is Liminality?

During the liminal phase, the subject develops an awareness that changes their “inmost nature.”[19] They acquire knowledge that prepares them for their new status. In the context of Baum’s article, this knowledge consists of “the marvels of life and the wonders of the universe” that are brought to a child’s notice and “registered upon the sensitive film” of their mind.[20] Consistent with both the fantastic nature of liminality as well as the Baum excerpt above, everything in Kansas is colorless like the “great gray prairie” (even Aunt Em), but The Land of Oz is:

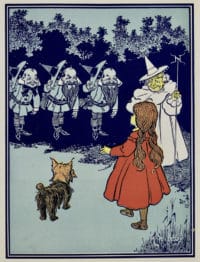

…a country of marvelous beauty. There were lovely patches of green sward all about, with stately trees bearing rich and luscious fruits. Banks of gorgeous flowers were on every hand, and birds with rare and brilliant plumage sang and fluttered in the trees and bushes. A little way off was a small brook, rushing and sparkling along between green banks, and murmuring in a voice very grateful to a little girl who had lived so long on the dry, gray prairies. While she stood looking eagerly at the strange and beautiful sights, she noticed coming toward her a group of the queerest people she had ever seen.[21]

The Witch of the North’s response to Dorothy’s question about the existence of witches in Oz reinforces its liminal status. The Good Witch explains that “in the civilized countries I believe there are no witches left, nor wizards, nor sorceresses, nor magicians. But, you see, the Land of Oz has never been civilized.[22] In other words, Oz does not represent one of the stable points within Dorothy’s transition. As noted, those are represented by Kansas.

Instead, The Land of Oz is topsy-turvy and chaotic, the defining characteristics of liminality. Oz is also “cut off from all the rest of the world,” which parallels the isolation of ritual subjects from the larger community during the liminal stage of their initiation. “Therefore,” the Witch of the North states, “we still have witches and wizards amongst us.”[23] Because liminality is where the transformative magic happens. __________

Oz as Liminal Space.

Ritual devices, things like masks, figurines, and body paint used by traditional societies during the liminal phase in rites of passage, are created by taking cultural elements out of their usual contexts and re-configuring them into something new, something that doesn’t exist in reality. Though these materials can be monstrous, the point is less about terrifying initiates out of their wits, than it is about making them “vividly and rapidly aware” of important aspects of their culture.[24] The purpose of these devices is to startle initiates into thinking about objects, relationships, and aspects of their environment they have taken for granted up to this point. Or, in the context of Baum’s article, “marvels of life and wonders of the universe” that hadn’t registered in their minds before.

The fanciful characters in The Land of Oz are consistent with this recombination of elements, confirming Oz’s liminality. A living scarecrow and talking lion are just for starters, not to mention the bear-tiger combo called the Kalidah, flying monkeys, and combative trees. Then there are the field mice organized as a monarchy, people who are made of porcelain, and the Quadlings who have no arms but a spring-loaded head. If these don’t say liminality, I don’t know what does!

But why does alluding to liminality make Baum such a successful writer of children’s books? Because doing so taps into what his young audience is experiencing during this stage of their development. As Baum notes, the fresh “realization of existence” sets every nerve “tingling with excitement.”[25] He may have found it surprising that other adults “so evidently fail to grasp” the mentality of those taking their “first peep” at the world, but Baum clearly understood their mindset.[26]

Since Baum’s aim was to write a wonder tale for the children of his day, it’s understandable that The Wonderful Wizard of Oz reflects the culture he, and they, experienced. Symbolism associated with the stages in Dorothy’s transition are inspired by Baum’s life experience. For example, westward expansion was significant in nineteenth-century America, with a lot of people moving into tornado-prone areas. Seeing the west as a place “where an intelligent man may profit,” Baum was among them.[27] He published a newspaper called the Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer, and one article he wrote involved a tornado that launched a pig hiding in a buggy a distance of 300 feet. Happily, the pig was uninjured, but more importantly Baum had the inspiration for Dorothy and Toto’s arrival in Oz.[28]

Needless to say, the cyclone that sets the story in motion represents the separation phase within rites of passage. The twister literally detaches Dorothy from the dry, colorless Kansas prairie, and symbolically speaking, the mode when a child lacks the understanding that they’re “a component part of mighty creation.” When the cyclone hits, Dorothy is taking shelter in the family’s empty farmhouse. Being alone in an empty house is a common dream symbol for an old personality structure, which underscores the symbolic link to Dorothy’s childhood development.[29] __________

Entering the Liminal Stage.

Upon landing in Oz (on top of the Wicked Witch of the East to be precise), Dorothy enters the liminal stage of her transition. And she is promptly greeted by the Witch of the North, who functions as the village elder responsible for shepherding an initiate through their rite of passage. Much has been written about Baum’s connection to Theosophy, an esoteric movement that emerged in the late nineteenth century. The Witch of the North parallels the wisdom’s “world Mother,” who in a very real sense, takes “all the women of the world” under Her charge.[30] Which is precisely what she does with Dorothy.

Naturally, the witch’s association with the North suggests a connection to the Pole Star, which according to Theosophy keeps a “watchful eye” on the “Imperishable Sacred Land” around the North Pole.[31] Consistent with this imagery, the Witch of the North gives Dorothy a protective talisman – a kiss on the forehead. The kiss is clearly a nod to what is known in Theosophy as “Dangma’s opened eye,” the inner spiritual eye of an advanced student.[32]

The Witch of the North ultimately sends Dorothy to the City of Emeralds, in the hope of an audience with the Great Wizard. But not before she puts on the silver shoes that previously belonged to the Witch of the East, which marks Dorothy’s acceptance of her role in this rite of passage. The road that will lead Dorothy to the City of Emeralds is famously paved with yellow brick, an image that recalls Baum’s years at military school in Peekskill, NY., a manufacturing center of Dutch paving bricks, which are bright yellow in color.[33] __________

A Fellowship of Initiates.

The liminal stage within rites of passage includes a series of trials. These tests serve to determine if the subject is ready to assume their new standing in the community. In collective rites (especially from childhood to adulthood), they are also intended to promote a bond among initiates. The fellowship that forms during this period surpasses distinctions of rank, age, kinship position, and in some cultures even gender.[34]

The Scarecrow is, of course, the first of Dorothy’s new-found companions. And meeting him is significant because he’s the first being Dorothy comes across who embodies the recombining of elements inherent in the liminal phase. She’s obviously getting deeper into liminality. After traveling together for a few hours, the road begins to get rough, and “the farther they went the more dismal and lonesome the country became.”[35] It’s clear she’s about to encounter the testing aspect of liminality, especially since the pair come to a great dark forest which is a traditional threshold symbol, as well as a place of testing and initiation.[36]

In keeping with the “comradeship” that forms as a result of the trials within the liminal phase, the Tin Woodman and the Lion join Dorothy’s party during her journey through the forest. The Scarecrow is reconfigured from Baum’s childhood nightmares, but he also reflects the significance of American farmers during this period.[37] The Tin Woodman looks like a display Baum put together for a hardware store during his days as a window dresser. But more importantly, being a mechanical man, he signifies the rapid industrialization of the times. In the context of liminal recombining, he is the grafting of twentieth-century technology to the fairy tale tradition.[38] The Cowardly Lion’s very nature, and ability to speak deem him a liminal character. And he’s been said to represent orator and politician William Jennings Bryan.[39] __________

Dorothy’s Trials.

Consistent with the forest’s capacity as a testing ground, the group’s progress is thwarted when they come upon a great gulf that blocks their path. After some considerable thought as to what they should do, the Scarecrow devises a plan to build a makeshift bridge.

Just as Dorothy and company start to cross the bridge, a pair of Kalidahs, “monstrous beasts” with incredibly sharp claws, comes charging toward them.[40] But after some roaring and wielding of the Tin Woodman’s axe, the troop manages to send the “ugly, snarling brutes” to the bottom of the gulf.[41]

The “Deadly Poppy Field” is yet another trial the group faces.[42] The Queen of the Mice owes Dorothy and friends a favor for saving her from a wildcat. So, the queen gathers her people to help rescue the Lion, who has succumbed to the poppies’ stupefying fragrance.[43]

Next Comes the Ordeal.

Many cultures describe rites of passage as “growing” a child into an adult.[44] Which is why they typically include an ordeal of some sort, one that signifies the dissolution of the initiate’s previous state.[45] Needless to say Dorothy’s ordeal is to kill the Witch of the West. The fact that there’s no road to the Witch of the West’s castle underscores the distinction between this undertaking, and the tests Dorothy and friends encountered in the forest. But after several run-ins with the witch’s minions, including the famous encounter with flying monkeys, Dorothy accomplishes her task. And given that the purpose of such liminal ordeals is dissolution of the initiate’s previous state, it’s only fitting that Dorothy succeeds in her ordeal by melting the Witch away to a “brown… shapeless mass,” which she promptly sweeps “out the door.”[46]

After wrapping up a few loose ends with the Winkies, Dorothy and company return to Emerald City. Because the Scarecrow, the Tin Woodman, and the Cowardly Lion are from the Land of Oz, the tokens the Wizard gives them are enough to achieve new status. Dorothy, on the other hand, needs to get back to Kansas in order to carry out the final, re-incorporation phase of her rite of passage. But the Wizard is proven to be a fraud, and unable to send Dorothy home.

So, at the suggestion of the guardian of Emerald City’s gate, the group is off to ask Glinda, Witch of the South, for help. As Oz scholar Michael Patrick Hearns suggests, the adventures that take place on their way to Glinda’s castle allow Dorothy’s companions to utilize their new skills, and embrace their hard-won status.[47] Dorothy, on the other hand, remains betwixt & between.

And Finally, On to Re-incorporation.

Shortly after the troop arrives at her castle, Glinda advises Dorothy that all she has to do is “knock the heels” of her Silver Shoes together three times, and command them to carry her wherever she wishes to go.[48] And before Dorothy knows it, she’s back in Kansas, sitting in front of her family’s new farmhouse, “built after the cyclone had carried away the old one.”[49] While the house that Dorothy was carried away in symbolizes her old personality structure, this one represents the new mode of being Dorothy has just attained. And Aunt Em “folding the little girl in her arms,” constitutes rites of incorporation.[50]

Dorothy has completed her transition. We know this for a couple of reasons. First, she has shed the silver shoes she’d been wearing throughout her journey in Oz. But more importantly, in that it’s developmentally significant, prior to the cyclone Dorothy didn’t engage with either Uncle Henry or Aunt Em. In fact, Baum explicitly states that her only interaction was with Toto, which signifies her lack of understanding that she’s “a component part of mighty creation.”[51]

So, their hug isn’t about Dorothy’s new-found appreciation for Aunt Em. Dorothy has loved Aunt Em from the beginning. Not only was Dorothy concerned that Em would be worrying about her, returning to Em was the entire motivation for Dorothy’s journey. After taking out the Witch of the West, Dorothy could have claimed the Yellow Castle for herself and lived quite comfortably with her friends in Oz forever. Instead, she returned to Emerald City to claim the Wizard’s promise to send her back to Kansas.

What Dorothy’s hug for Em does signify, is that her mind “has absorbed the astonishing circumstances of [her] environment.” Dorothy is deliberately (and quite literally) embracing “the practical details of worldly experience,” the world of the broad Kansas prairie, where the days are filled with activities like milking cows and watering the cabbages.

In Conclusion.

Dorothy may have returned to Kansas, but she isn’t right back where she started. She has been transformed. She is now, as Baum described it, “filled with unalloyed vigor” and ready to step “upon the threshold” of life.[52] And Dorothy’s transition to this new mode of being was brought about by her journey through liminality, as signified by Oz, a land betwixt & between. The Wonderful Wizard of Oz is indeed a wonder tale. And the realization that it’s more than just a fun ride on an adventurous narrative makes it even more wonderous.

Endnotes:

[1] Baum, L. Frank, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. (New York: Harper Collins, 1987), 1.

[2] The Wizard of Oz: An American Fairy Tale. Library of Congress Exhibitions.

[3] Field, Hana. “Years of Censoring ‘Oz.’” Chicago Tribune. (May 8, 2000).

[4] Rosenthal, Kristina. The University of Tulsa Special Collections.

[5] Baum, 1; “Dorothy the Librarian.” Life Magazine. (Feb. 16, 1959), 47; Field.

[6] Taylor, Stuart. “Justices Refuse to Hear Tennessee Case on Bible and Textbooks.” The New York Times. (Feb. 23, 1988).

[7] The Gazette (Montreal). (Oct. 25, 1986).

[8] Taylor.[9] Hesse, Hermann. “On Reading Books.” in My Beliefs: Essays on Life and Art. Edited by Theodore Ziolkowski, translated by Denver Lindley. (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1974), 101.

[10] Baum, Frank L. “What Children Want.” Chicago Evening Post. (November 27, 1902).

[11] Baum What Children Want.

[12] Baum What Children Want.

[13] Turner, Victor. “Betwixt and Between: The Liminal Period in Rites of Passage.” Betwixt & Between: Patterns of Masculine and Feminine Initiation. Edited by Lois Carus Mahdi, Steven Foster, Meredith Little. (La Salle, Illinois: Open Court, 1987), 7.

[14] Van Gennep, Arnold. The Rites of Passage. Translated by Monika B. Vizedom and Gabrielle L. Caffee. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1960), 10; Eliade, Mircea. Rites and Symbols of Initiation: The Mysteries of Birth and Rebirth. Translated by Willard R. Trask. (New York: Harper & Row, 1958), xiii.

[15] Baum What Children Want.

[16] Baum What Children Want.

[17] Turner, Victor. From Ritual to Theatre: The Human Seriousness of Play. (New York: Performing Arts Journal Publications, 1982), 41.

[18] Turner, Victor. The Forest of Symbols: Aspects of Ndembu Ritual. (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1967), 97; Turner, Victor. “Betwixt and Between: The Liminal Period in Rites of Passage.” Betwixt & Between: Patterns of Masculine and Feminine Initiation. Edited by Lois Carus Mahdi, Steven Foster, Meredith Little. (La Salle, Illinois: Open Court, 1987), 7.

[19] Turner Betwixt and Between, 11.

[20] Baum What Children Want.

[21] Baum Oz, 22.

[22] Baum Oz, 28.

[23] Baum Oz, 28.

[24] Turner Betwixt and Between, 14.

[25] Baum What Children Want.

[26] Baum What Children Want.

[27] Koupal, Nancy Tystad. “The Wonderful Wizard of the West. L. Frank Baum in South Dakota, 1888-91.” Great Plains Quarterly. (Fall 1989), 204.

[28] Schwartz, Evan I. “Matilda Joslyn Gage-the Unlikely Inspiration for the Wizard of Oz.” Historynet.com

[29] Jones, Raya A. “A Discovery of Meaning: The case of C. G. Jung’s house dream.” Working Paper 79. School of Social Sciences. Cardiff University, 9; Peterson, Deb. “The Hero’s Journey: Refusing The Call to Adventure.” ThoughtCo.com.

[30] Leadbeater, C. W. The World Mother As Symbol and Fact. (Madras, India: The Theosophical Publishing House, 1928), 1-2.

[31] Blavatsky, H. P. The Secret Doctrine Vol. II-Anthropogeneis, (New York: The Theosophical Publishing Co, 1888), 6, 400, 6.

[32] Blavatsky Secret Doctrine, 6, 400, 6.

[33] Schwartz, Evan. Finding Oz: How L. Frank Baum Discovered the Great American Story. (New York: Houghton, Mifflin, 2009), 13.

[34] Turner Forest of Symbols, 100-101.

[35] Baum Oz, 51-52.

[36] Cooper, J. C. An Encyclopaedia of Traditional Symbols. (High Holborn: Thames and Hudson, 1987), 72.

[37] Gourley, Catherine. Media Wizards: A Behind-the-scenes Look at Media Manipulations. (Brookfield, Connecticut: Twenty-First Century Books, 1999), 7.

[38] Haas, Joseph. “A Little Bit of ‘Oz’ in Northern Indiana.” Indiana Times, May 3, 1965; Gardner, Martin and Russell B. Nye editors. The Wizard of Oz and Who He Was. (East Lansing: Michigan University Press, 1994), 7.

[39] Littlefield, Henry M. “The Wizard of Oz: Parable on Populism.” American Quarterly, Vol. 16, No.1, 53.

[40] Baum Oz, 93.

[41] Baum Oz, 94-97.

[42] Baum Oz, 102.

[43] Baum Oz, 122.

[44] Turner Forest of Symbols, 101-102.

[45] Turner, Victor. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. (New York: Cornell University Press, 1969), 103.

[46] Baum Oz, 182.

[47] Hearn, Michael Patrick. The Annotated Wizard of Oz. (New York: Norton, 2000), 313.

[48] Baum Oz, 303.

[49] Baum Oz, 305.

[50] Baum Oz, 307.

[51] Baum What Children Want.

[52] Baum What Children Want.

Images:

Title page. Baum, L. Frank. Illustrated by William Wallace Denslow. The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. (New York: Geo. M. Hill Co, 1900). Public domain. Source: Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia Library via Wikimedia https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Wonderful_Wizard_of_Oz,_006.png

Image has been retouched by user.

All other illustrations from Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz:

Baum, L. Frank. Illustrated by William Wallace Denslow. The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. (New York: Geo. M. Hill Co, 1900). Public domain.

Source: Library of Congress Children’s Book Selections. https://www.loc.gov/free-to-use Item number- https://lccn.loc.gov/03032405

Rites of Passage table constructed by author.

FYI:

This Book is Banned participates in the Amazon.com affiliate program, where we earn a small commission by linking to books (but the price remains the same to you). This allows us to remain free, and ad free. [Our privacy policy]

ometimes that well-worn adage doesn’t really mean what our literal-minded, text-focused, Google-driven world thinks it means. One reason this happens is that, quite simply, language evolves.

ometimes that well-worn adage doesn’t really mean what our literal-minded, text-focused, Google-driven world thinks it means. One reason this happens is that, quite simply, language evolves.

he idea for

he idea for

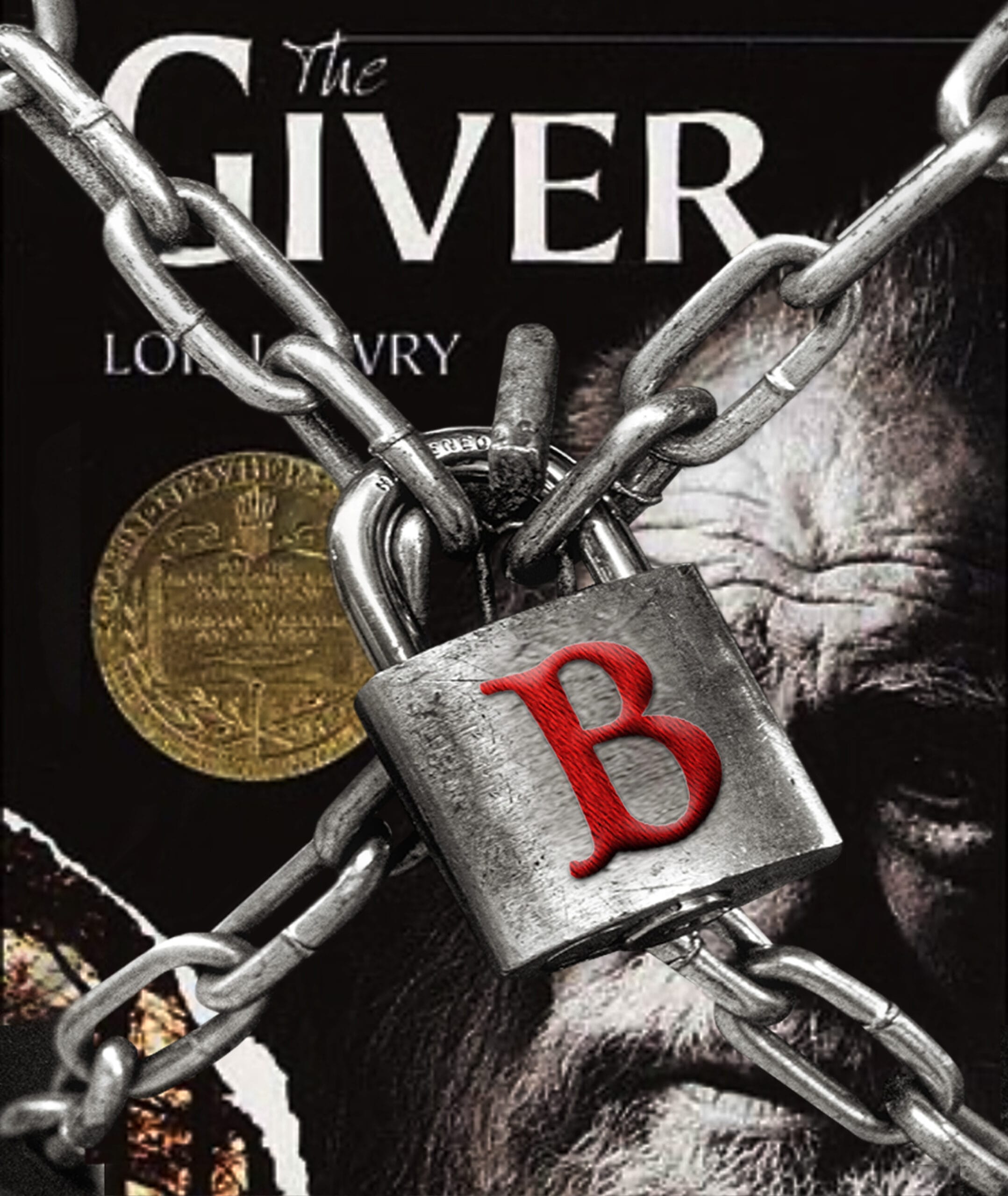

e live in a culture spellbound by censorship. The terms, of course, have changed, but “cancelling,” “boycotting,” “embargoing,” etc. all lead to a similar result —suppressing works of art from full and free consideration by the open-minded. And, of course, the central actor in the drama is no longer the federal government. Now, non-state actors with social media bullhorns amplifying their views, stand at the ready to keep books under lock and key.

e live in a culture spellbound by censorship. The terms, of course, have changed, but “cancelling,” “boycotting,” “embargoing,” etc. all lead to a similar result —suppressing works of art from full and free consideration by the open-minded. And, of course, the central actor in the drama is no longer the federal government. Now, non-state actors with social media bullhorns amplifying their views, stand at the ready to keep books under lock and key.

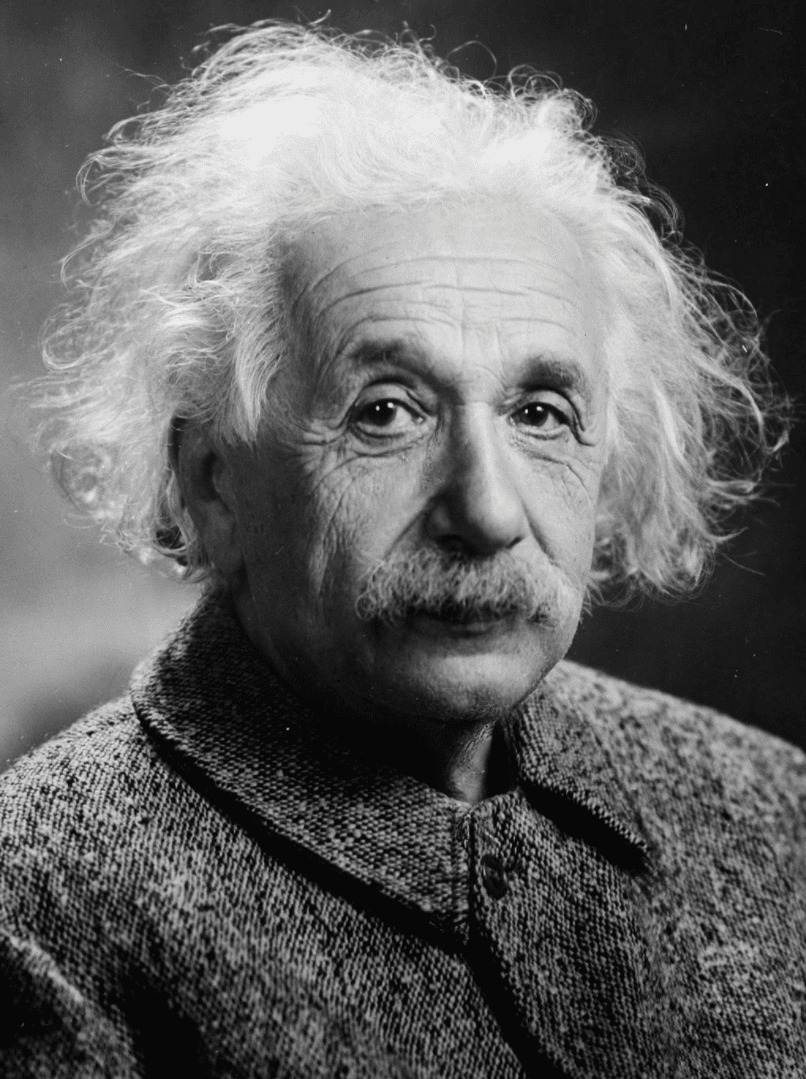

Albert Einstein is literally the face of the STEM education so highly regarded in society today. We see his likeness on countless numbers of brochures for science programs, camps, and fairs. But, what did Einstein himself say about education? A lot of us would be shocked to discover that he championed a

Albert Einstein is literally the face of the STEM education so highly regarded in society today. We see his likeness on countless numbers of brochures for science programs, camps, and fairs. But, what did Einstein himself say about education? A lot of us would be shocked to discover that he championed a