N

N

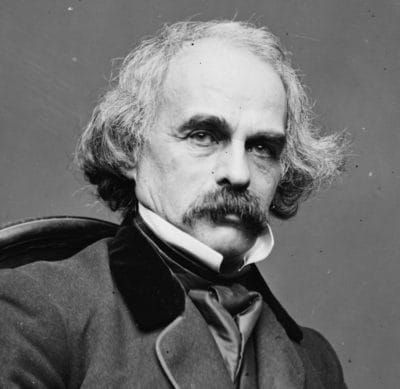

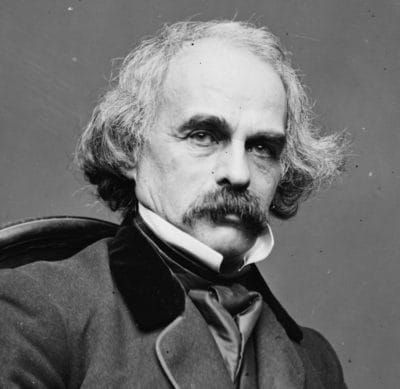

athaniel Hawthorne is renowned for deep symbolism and psychological insight. So, what’s The Scarlet Letter really about? It’s definitely about more than a misbehaving minister.

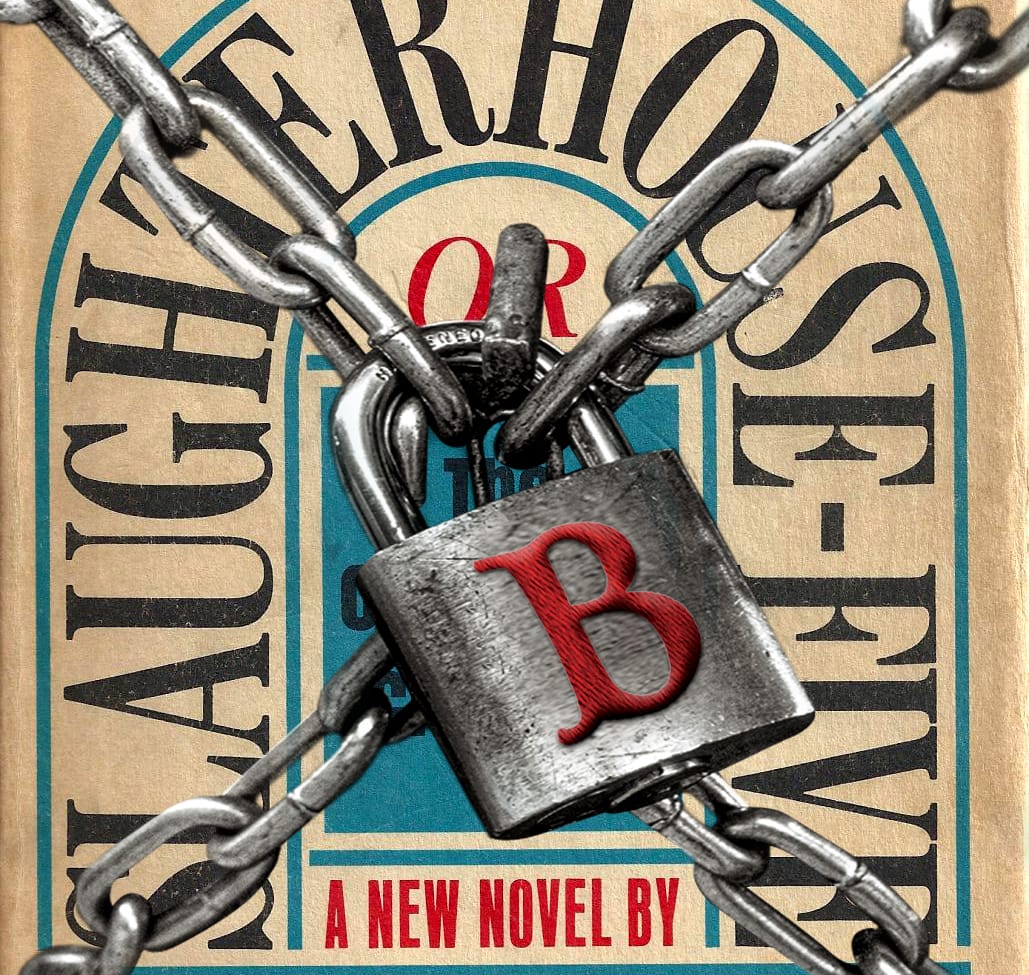

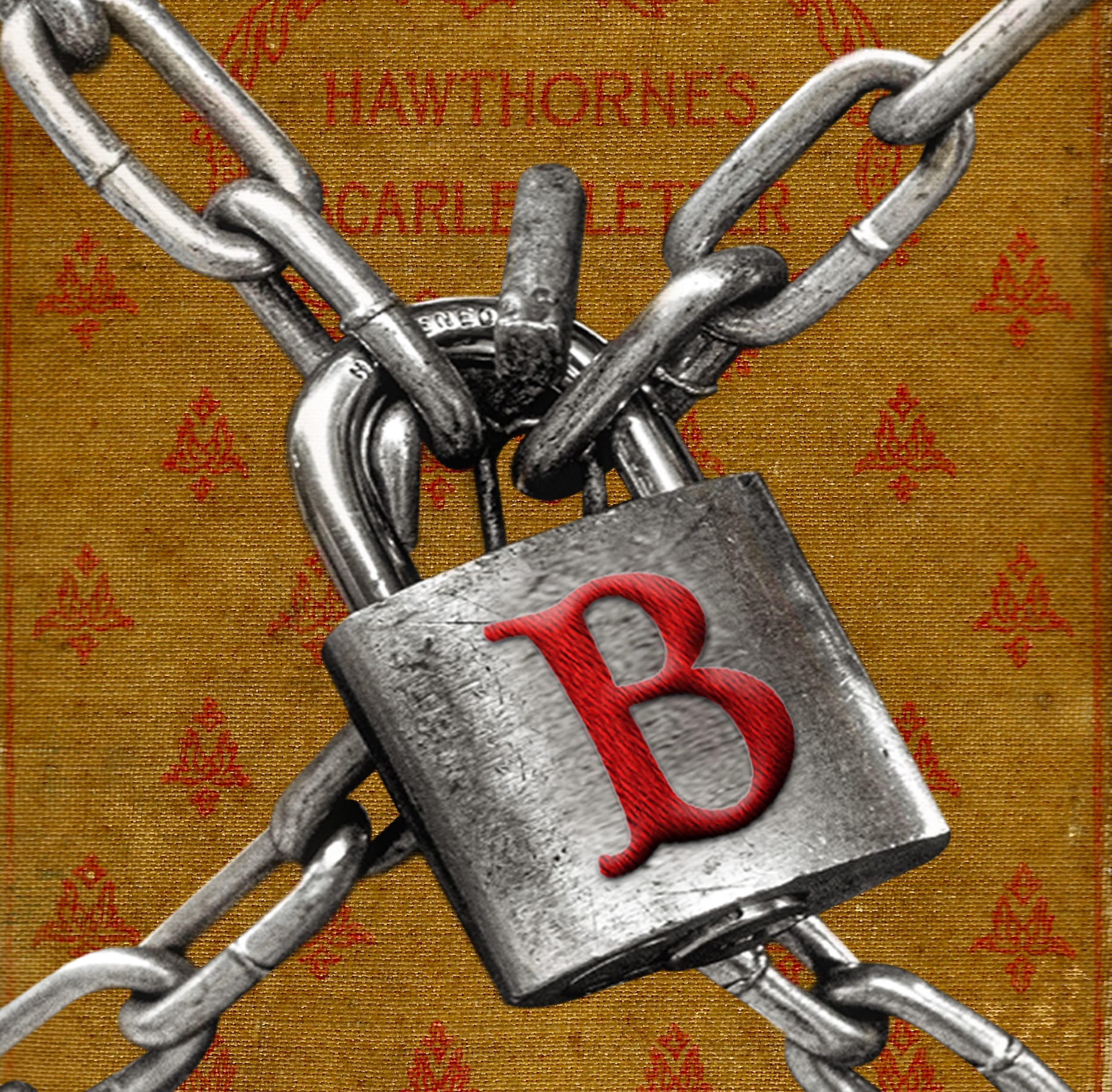

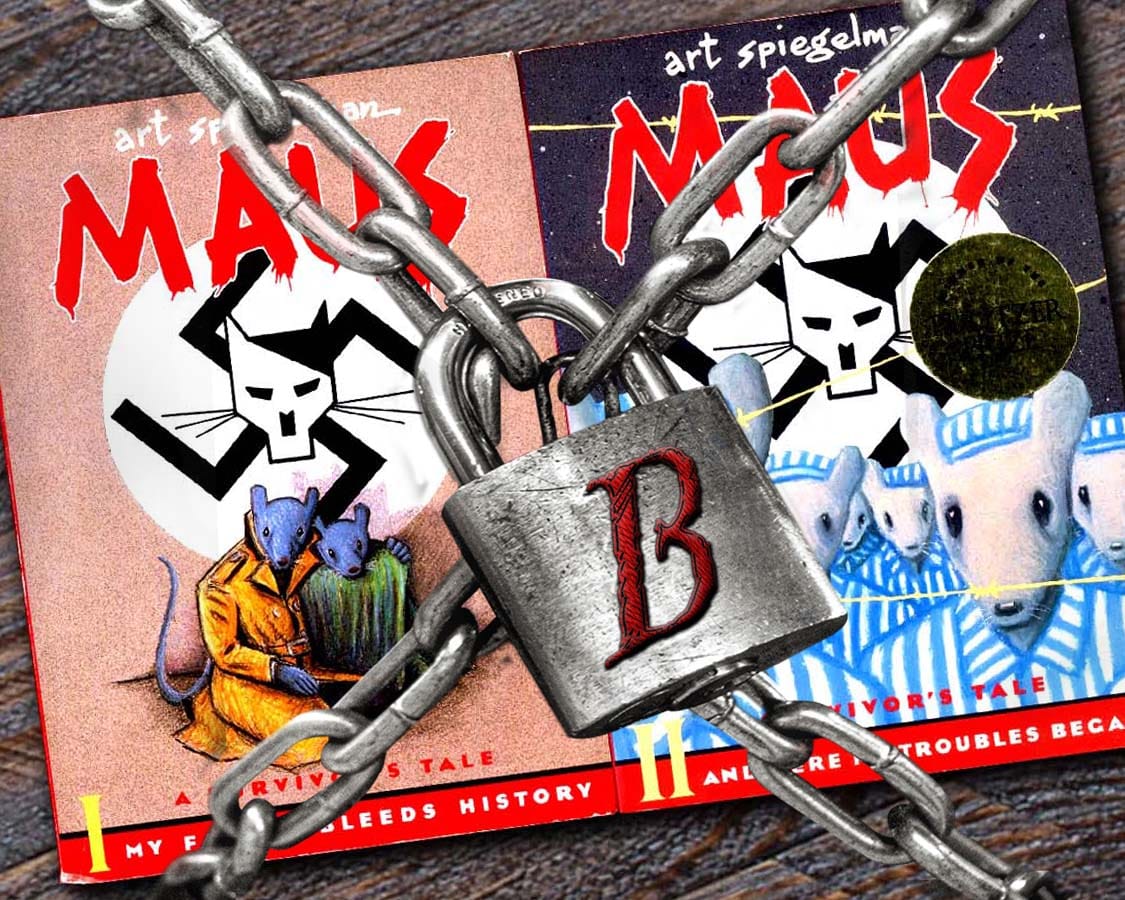

Unlike a lot of other books, there’s no short answer as to why The Scarlet Letter was banned. Whenever Hawthorne’s work has been challenged, the objections have come from all directions. That’s because Nathaniel Hawthorne had a complicated relationship with his subject matter. Needless to say, Hawthorne is inextricably linked with Puritanism. He wrote The Scarlet Letter, after all.

When we read a book, it’s important to consider the author and their historical context. And, when we read Hawthorne, it’s important to understand that his relationship with Puritanism falls squarely in the love/hate category. That’s especially apparent in The Scarlet Letter.

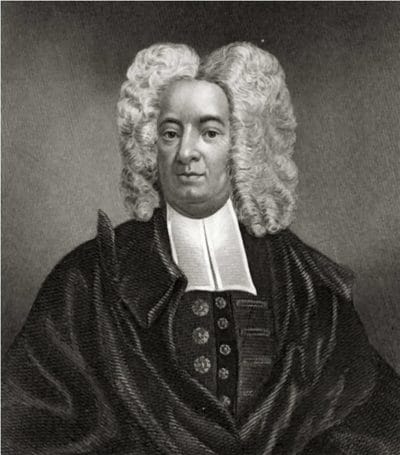

It’s no secret that Hawthorne was haunted by his Puritan lineage. He was so bothered, he added the letter W to his name to separate himself from his Puritan forefathers.[1] It’s easy to see why. His great, great, great grandfather, Major William Hathorne, was infamous as a “bitter persecutor” of Quakers, having them “scourged out of town.”[2] Hathorne is mostly remembered for ordering “Anne Coleman and four of her friends” to be whipped, while tied to a cart and forced to walk the 60 miles from Salem to Boston.[3] And William’s son, John, “made himself conspicuous” as a “witch judge” and chief interrogator during the Salem Witch Trials.[4]

Hawthorne talks about the ancestral guilt he carries as a result of their actions in The Custom House, the opening chapter of The Scarlet Letter. He ends the passage by praying that any family curse caused by their actions “may be now and henceforth removed.”[5] These feelings are undoubtedly the source of what Herman Melville described as the “mystical blackness” that pervades Hawthorne’s work.[6]

On the other hand, Hawthorne still wasn’t inclined to embrace the religious shift that had occurred in New England during the nineteenth century, toward individual experience and an optimistic faith in the perfectibility of human beings.[7] His Puritan ancestry gave Hawthorne a sense of rootedness, “a home-feeling with the past.”[8] And he may not have been a “churchly man,” but his heritage gave him an appreciation for the culture and moral foundation that emerged from Puritan doctrine.[9] His very nature, it’s been said, was imbued with “the temperamental earnestness of the Puritan.”[10]

It’s no surprise, then, that multiple and often paradoxical perspectives are common in Hawthorne’s works. In fact, Hawthorne’s technique has been referred to as “the device of multiple choice.”[11] Hawthorne himself described The Scarlet Letter as “turning different sides” of the same idea “to the reader’s eye.”[12] So, it should be even less surprising that The Scarlet Letter has been banned and challenged for contradictory reasons as well.

For example, one literary critic reviewing The Scarlet Letter the year it was published thought Hawthorne’s depiction of Puritanism was too severe. He didn’t say Hawthorne was wrong. He just wondered why, “of all features of the period,” Hawthorne chose practices that “reflect most discredit” on the Puritans.[13]

Another early critic, however, thought Hester’s punishment wasn’t painful and obvious enough. Merely being condemned to wear the scarlet letter didn’t make Hester contrite. It didn’t make her repent. And Hawthorne didn’t “excite the horror of his readers” enough to keep them from following in Hester and Dimmesdale’s footsteps.[14]

So, it isn’t just the passage of time that causes contemporary readers to see oppressive patriarchy (like the Seattle teacher who tweeted he’d “rather die” than teach The Scarlet Letter), when some nineteenth-century critics found what we would call feminism.[15] It isn’t caused by cultural shift. And it’s more than Hester’s “light punishment” that lead to objections about how the book advocates women’s rights. Reverend Arthur Cleveland Coxe specifically expressed concern that Hawthorne’s book encouraged a message way too close to views expressed at the first National Woman’s Rights Convention, held in Worcester, Massachusetts the same year The Scarlet Letter was published.[16]

Granted, we’re more on the lookout for feminist themes these days. But, they were clearly in the text all along. And, they’re right beside passages that seem to say Hester should accept her fate, and fall in line with patriarchal Puritan society.

It is true, however, that the most consistent objection to The Scarlet Letter has been the topic of adultery. The notion that adultery is quite simply not a “fit subject for popular literature” didn’t begin with the 1961 challenge in Michigan, or the Arizona challenge in 1967.[17] That mindset has been around since 1850. And there’ll probably always be someone who takes offense at Hawthorne’s use of adultery as a vehicle for examining his multiple perspectives and paradoxical themes. Unfortunately, this mindset squashes any real understanding of what The Scarlet Letter has to say. And this superficial (mis)reading begins with the title.

After all, if the focus of Hawthorne’s book was the scandalous behavior of an adulterous woman, he would’ve titled it Hester Prynne, or A Fallen Woman.[18] That would have been more consistent with the novels of adultery that were popular in nineteenth-century literature, like Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, or Madame Bovary by Flaubert.[19] While these novels revolve around the theme of “love against the world,” Hawthorne calling his work The Scarlet Letter tells the reader that the letter’s function as symbol is actually the central subject of the book.[20]

This reading is reinforced by the fact that Hester and Dimmesdale’s adulterous act isn’t depicted (even in nineteenth-century terms), and the word adultery never appears in the text. Yes, requiring that a capital A be stitched to your clothes a historically accurate penalty for adultery in Puritan Massachusetts. But, the law is precise about its size and placement. Hester embellishing the letter with gold threat would not have been tolerated. And other aspects of the punishment Hawthorne depicts don’t line up with the statute’s requirements.[21] Hawthorne is clearly using the scarlet letter as a symbol, a word that does appear in his book some twenty-four times, specifically in reference to the A on Hester’s bosom.[22] The question at the heart of Hawthorne’s work, then, is “What does the scarlet A actually mean?”

___

The Custom House.

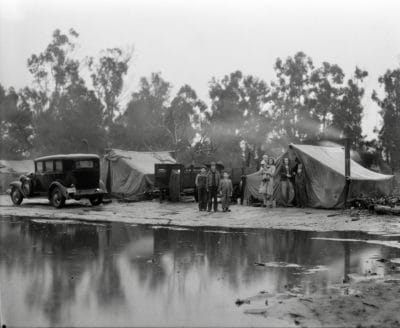

The opening chapter of the book provides a cryptic key, so to speak, to unlocking Hawthorne’s symbolism, enabling readers to see that The Scarlet Letter is about more than a misbehaving minister. By locating the red cloth letter that inspired his work in Salem’s Custom House, wrapped in a package from before the Revolutionary War, Hawthorne establishes a connection between seventeenth-century Puritan New England and nineteenth-century American culture.

In this context, the A becomes a cultural artifact, one that simultaneously expresses Hawthorne’s culture as well as the one that produced it.[23] Hawthorne reaches back through the A to America’s myth of national origins and does what we continue to do, return to the Puritans to reclaim a sense of purpose, while also demonstrating progress. The A embodies the shift from Puritanism to the Revolution, as well as America’s continued development from that time forward.[24]

The American Revolution prompted social changes just as significant as the political changes it brought about. The spirit that triggered the Revolution, with its declaration of inalienable rights, self-evident truths, and the equal creation of all, undoubtedly played a role in the decline of Puritanism and its foundational Calvinist doctrine, a theology that emphasizes the depravity of humankind.[25] Hawthorne considers this transition from the religious perspective, a psychological outlook, as well as a historical viewpoint, all of which are reflected in the book.

___

Dimmesdale looks back,

and Hester is forward looking.

Founders of new ethics are invariably deemed sinful/heretical, because they challenge the authority of an existing/old ethic, a collective whose aim is to maintain equilibrium. And that’s the case in The Scarlet Letter. Hester Prynne, who is forced to literally wear a label identifying her as sinful, represents a new ethic. And Arthur Dimmesdale is a concrete expression of the American Puritanism that Hester challenges. Not only is Dimmesdale a Puritan minister, he embodies the psychological consequences associated with trying to adhere to such an authoritarian ethic. [26]

Guilt stemming from sinful acts is frequently identified as a major theme in The Scarlet Letter, but it’s more complicated than that. Two basic psychological mechanisms are at work within an authoritarian ethic like Puritanism (with its harshly implemented moral Laws and publicly enforced taboos), suppression, and repression. Suppression is the process of consciously pushing tendencies that don’t align with the ethical system out of our awareness. And the best-known forms of this technique are discipline and asceticism.[27]

Hawthorne is known as a master of psychological insight, and he tells us it’s “essential” to Dimmesdale “to feel the pressure of a faith about him.”[28] And we see Dimmesdale use both discipline and asceticism to keep himself in check. He exhibits discipline when he tells Pearl that he won’t appear publicly with her and Hester in the town square the next day:

“Nay; not so, my little Pearl,” answered the minister; for, with the new energy of the moment, all the dread of public exposure, that had so long been the anguish of his life, had returned upon him; and he was already trembling at the conjunction in which—with a strange joy, nevertheless—he now found himself.[29]

“Nay; not so, my little Pearl,” answered the minister; for, with the new energy of the moment, all the dread of public exposure, that had so long been the anguish of his life, had returned upon him; and he was already trembling at the conjunction in which—with a strange joy, nevertheless—he now found himself.[29]

As much as Dimmesdale might wish he could claim his place alongside Hester and Pearl, he doesn’t dare fly in the face of Puritanism’s moral Law. And suppressing that impulse becomes a pleasant experience in itself. It’s also revealed that Dimmesdale’s conflicted soul not only leads him to whip himself with a “bloody scourge,” but fast to the point of collapse as “act[s] of penance.”[30]

While suppression operates on the conscious level, repression functions on the unconscious level. Inclinations that are at odds with the dominant ethic are rejected from the conscious mind. These tendencies may become unconscious, but according to depth psychology, they “lead an active underground life of their own.”[31] Needless to say, nothing good can come from this situation.

What does happen is that two psychic systems develop within the personality, one an outgrowth of suppression, and the other a byproduct of repression. Suppression leads to a “façade personality,” a mask that signals we’re conforming to the dominant ethic of the age, and hides our true nature.[32] Though it’s easy to interpret Dimmesdale’s actions as mere hypocrisy, this is what occurs when he hides his guilt. [33] The scene at the scaffold when Hester is first released from prison, demonstrates a façade personality at work:

“Hester Prynne,” said he, leaning over the balcony and looking down steadfastly into her eyes, “thou hearest what this good man says, and seest the accountability under which I labor. If thou feelest it to be for thy soul’s peace, and that thy earthly punishment will thereby be made more effectual to salvation, I charge thee to speak out the name of thy fellow-sinner and fellow-sufferer! Be not silent from any mistaken pity and tenderness for him.[34]

“Hester Prynne,” said he, leaning over the balcony and looking down steadfastly into her eyes, “thou hearest what this good man says, and seest the accountability under which I labor. If thou feelest it to be for thy soul’s peace, and that thy earthly punishment will thereby be made more effectual to salvation, I charge thee to speak out the name of thy fellow-sinner and fellow-sufferer! Be not silent from any mistaken pity and tenderness for him.[34]

Dimmesdale makes his true feelings known. But he does so through a mask that signals to everyone but Hester that he’s conforming to the strict Puritan ethic.

The other psychic system that develops is a shadow figure, which is a byproduct of repression. Taboo impulses are rejected so emphatically they become psychologically severed as “not me,” and as mentioned above, take on a life of their own. Chillingworth embodies this shadow figure.[35] As such, he’s fully aware of what Dimmesdale is repressing. And his mission is to keep the torture of living under such an authoritarian ethic “always at red heat,” which literally drains the life out of Dimmesdale like the blood-sucking leech Hawthorne describes Chillingworth as.[36]

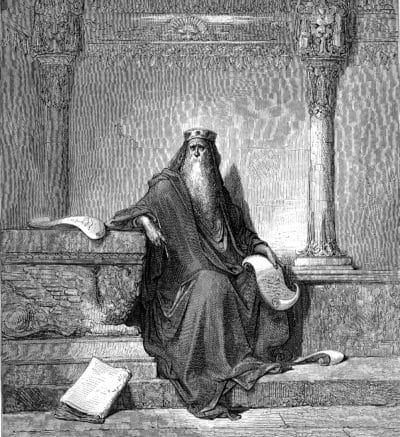

While Dimmesdale is an expression of American Puritanism, Hester looks toward a new ethic, and the social shifts that result from it. Like we said earlier, founders of new ethics are consistently deemed heretical. And Hawthorne associates Hester Prynne with Anne Hutchinson, who was expelled from Massachusetts Bay Colony during the seventeenth century. Hutchinson was banished for her role in the “Antinomian controversy,” a theological conflict that was essentially between power and freedom of conscience.[37]

By associating Hester with Hutchinson, Hawthorne indicates that Hester’s real crime is indeed heresy rather than simply breaching Puritanism’s rigid moral code (though she did that as well). A passage stating that Hester “assumed a freedom of speculation” our Puritan forefathers would have considered “a deadlier crime than that stigmatized by the scarlet letter” confirms this interpretation.[38] In associating Hester with Hutchinson, Hawthorne also characterizes her heresy as being antinomian in nature.[39]

At its root, antinomianism means “against or opposed to the law.”[40] In a Christian context, antinomianism embraces the existence of an “inner light” within every individual, which presumes a spirituality based on inner experience with the Holy Spirit rather than conformity to religious laws.[41] Hester’s antinomian tendencies are evident in her declaration to Dimmesdale, where she’s clearly judging the validity of their relationship through her conscience and inner spiritual experience rather than the Puritan power structure and religious Law:

What we did had a consecration of its own. We felt it so! We said so to each other! Hast though forgotten it?[42]

What we did had a consecration of its own. We felt it so! We said so to each other! Hast though forgotten it?[42]

Antinomianism’s “inner light” has been described as an “ancestor” to the philosophy of self-reliance held by nineteenth-century antinomians like Ralph Waldo Emerson and his circle of Transcendentalists. [43] Critics of unthinking conformity (religious or otherwise), the Transcendentalists urged each person to find, as Emerson put it, “an original relation to the universe.”[44] It’s a complex word, Transcendentalism, especially for such a simple idea – that men and women (in equal measure) have knowledge about the world around them that goes beyond what they can see, touch, hear, taste, or feel (transcends it, in other words). And, that people can trust their own intuition to know what is right.[45] Antinomianism’s “inner light” has clearly been influenced by the post-Revolutionary spirit mentioned earlier (with its secular notion of self-evident truths, declaration of inalienable rights, and the equal creation of all), resulting in these Transcendentalist principles.

Hawthorne became acquainted with the Transcendentalist circle during the years he and his family spent in free-thinking and reform-minded Concord, which brings us to Margaret Fuller and her influence on The Scarlet Letter.[46] Fuller is best known for her feminist work Woman in the Nineteenth Century, and she inspired Hawthorne’s “dark heroines,” the first of which was Hester Prynne.[47] In the chapter titled Another View of Hester, Hawthorne follows Fuller’s description of three stages in the advancement of women toward self-realization and social equality. The first stage is legal and institutional. Second is revised concepts about gender. And the third phase is female character itself, to primarily live in and for her own development.[48] According to Hester:

As a first step, the whole system of society is to be torn down, and built up anew. Then, the very nature of the opposite sex, or its long hereditary habit, which has become like nature, is to be essentially modified, before woman can be allowed to assume what seems a fair and suitable position. Finally, all other difficulties being obviated, woman cannot take advantage of these preliminary reforms, until she herself shall have undergone a still mightier change; in which, perhaps, the ethereal essence, wherein she has her truest lie, will be found to have evaporated.[49]

As a first step, the whole system of society is to be torn down, and built up anew. Then, the very nature of the opposite sex, or its long hereditary habit, which has become like nature, is to be essentially modified, before woman can be allowed to assume what seems a fair and suitable position. Finally, all other difficulties being obviated, woman cannot take advantage of these preliminary reforms, until she herself shall have undergone a still mightier change; in which, perhaps, the ethereal essence, wherein she has her truest lie, will be found to have evaporated.[49]

Those who knew Margaret Fuller best, described her as “The Friend:”

This was her vocation. She bore at her girdle a golden key to unlock all caskets of confidence. Into whatever home she entered she brought a benediction of truth, justice, tolerance, and honor.[50]

This was her vocation. She bore at her girdle a golden key to unlock all caskets of confidence. Into whatever home she entered she brought a benediction of truth, justice, tolerance, and honor.[50]

Consistent with her forward-looking role, by the end of The Scarlet Letter, this characterization also applies to Hester Prynne, marking the acceptance of the nineteenth century’s reform-minded ethic of individual experience and self-reliance.

[Women] came to Hester’s cottage, demanding why they were so wretched, and what the remedy! Hester comforted and counselled them, as best she might. She assured them, too, of her firm belief, that, at some brighter period, when the world should have grown ripe for it, in Heaven’s own time, a new truth would be revealed, in order to establish the whole relation between man and woman on a surer ground of mutual happiness.[51]

[Women] came to Hester’s cottage, demanding why they were so wretched, and what the remedy! Hester comforted and counselled them, as best she might. She assured them, too, of her firm belief, that, at some brighter period, when the world should have grown ripe for it, in Heaven’s own time, a new truth would be revealed, in order to establish the whole relation between man and woman on a surer ground of mutual happiness.[51]

___

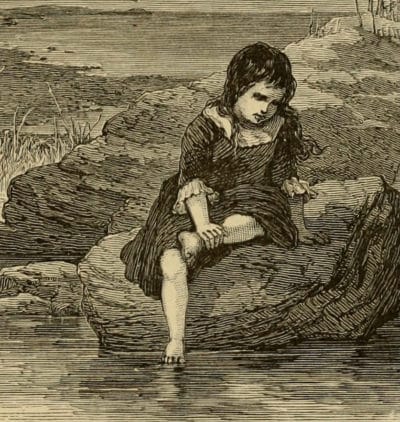

Pearl: Transition Personified.

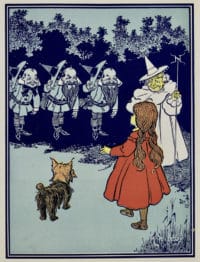

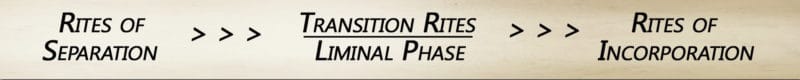

Symbolically speaking, children typically represent the future. Though Pearl is often associated with evil, it is the process of transition that she personifies. She embodies the chaotic liminal stage between one stable mode of being and another, when we are no longer in one mode, but not yet in another. We are “betwixt and between,” in this an old ethic and a new one. [52] Hester’s concerns about her daughter reflect the anxiety often experienced by those on the cusp of a new ethic, dreading the worst possible consequences while holding onto glimpses of the best possible outcome.[53]

[Hester] remembered—betwixt a smile and a shudder—the talk of the neighboring towns-people; who, seeking vainly elsewhere for the child’s paternity, and observing some of her odd attributes, had given out that poor little Pearl was a demon offspring; such as, ever since old Catholic times, had occasionally been seen on earth, through the agency of their mother’s sin, and to promote some foul and wicked purpose. Luther, according to the scandal of his monkish enemies, was a brat of that hellish breed.[54]

[Hester] remembered—betwixt a smile and a shudder—the talk of the neighboring towns-people; who, seeking vainly elsewhere for the child’s paternity, and observing some of her odd attributes, had given out that poor little Pearl was a demon offspring; such as, ever since old Catholic times, had occasionally been seen on earth, through the agency of their mother’s sin, and to promote some foul and wicked purpose. Luther, according to the scandal of his monkish enemies, was a brat of that hellish breed.[54]

The new ethic alluded to by mentioning Luther is, of course, nothing less than the establishment of Protestantism itself. Pearl, however, specifically represents the transition between seventeenth-century Puritanism, and the new, nineteenth-century ethic. She is, after all, the daughter of Arthur Dimmesdale and Hester Prynne:

Her nature appeared to possess depth, too, as well as variety; but—or else Hester’s fears deceived her—it lacked reference and adaptation to the world into which she was born. The child could not be made amenable to rules. In giving her existence, a great law had been broken; and the result was a being whose elements were perhaps beautiful and brilliant, but all in disorder. [55]

Her nature appeared to possess depth, too, as well as variety; but—or else Hester’s fears deceived her—it lacked reference and adaptation to the world into which she was born. The child could not be made amenable to rules. In giving her existence, a great law had been broken; and the result was a being whose elements were perhaps beautiful and brilliant, but all in disorder. [55]

As Hawthorne shows us, Pearl possesses Dimmesdale’s depth of character, but also has Hester’s antinomian nature. As a child, however, she’s developing and evolving, like the young country of America itself.

___

The love plot parallels the shift in American culture.

The arc of Hawthorne’s love story reflects the shift in American culture that occurred between the conflicting ethics that Dimmesdale and Hester embody. The tale begins in Boston, the very colony established by John Winthrop, and the Puritan forefathers credited with founding America, those we still envision in black cloaks and steeple-crowned hats. And Hawthorne explicitly states that at this point in America’s history, Boston is a theocracy, a form of government where religion and law are “thoroughly interfused.”[56]

We’re introduced to Hester as she is released from prison, and crosses the threshold of its heavy oaken door, a significant symbol indicating change. Hawthorne makes it clear that her thinking (and therefore the ethic she embodies) conflicts with the strict, authoritarian Puritan doctrine. After all, Hester is being released from prison, where (not coincidently) she gave birth to baby Pearl (and all that she embodies). In this scene, we also learn that Dimmesdale is an integral part of the theocratic machinery. And Hawthorne drops enough hints that we know he’s the father of Hester’s baby.

Hawthorne spends the next segment of the narrative examining the differing ethics at work, and their psychological repercussions. The love story peaks with the scene in the forest between Hester and Dimmesdale, when she proposes that they put the past seven years behind them, leave Boston, and start a new life somewhere else:

Begin all anew! Hast thou exhausted possibility in the failure of this one trial? Not so! The future is yet full of trial and success. There is happiness to be enjoyed! There is good to be done![57]

Begin all anew! Hast thou exhausted possibility in the failure of this one trial? Not so! The future is yet full of trial and success. There is happiness to be enjoyed! There is good to be done![57]

Hester’s plan involves more than a future with Dimmesdale. Symbolically, her proposal amounts to a re-founding of America on the basis of nineteenth-century principles – development of the self, individual experience and self-reliance, as well as the new morality and corresponding social forms they give rise to.[58]

If real progress is to take place, however, Pearl must come to terms with Dimmesdale, which she finally does:

Pearl kissed [Dimmesdale’s] lips. A spell was broken. The great scene of grief, in which the wild infant bore a part, had developed all her sympathies; and as her tears fell upon her father’s cheek, they were the pledge that she would grow up amid human joy and sorrow, nor forever do battle with the world, but be a woman in it. Towards her mother, too, Pearl’s errand as a messenger of anguish was all fulfilled.[59]

Pearl kissed [Dimmesdale’s] lips. A spell was broken. The great scene of grief, in which the wild infant bore a part, had developed all her sympathies; and as her tears fell upon her father’s cheek, they were the pledge that she would grow up amid human joy and sorrow, nor forever do battle with the world, but be a woman in it. Towards her mother, too, Pearl’s errand as a messenger of anguish was all fulfilled.[59]

With Pearl’s kiss, seventeenth-century Puritanism and the nineteenth-century’s antinomian ethic of self-reliance are symbolically married, if you will.[60] And with that, Dimmesdale passes away, just like the era defined by Puritanism ultimately did. Signifying Puritanism’s continued influence on America, Chillingworth bequeaths “a great deal of property, both here and in England” (the birthplace of Puritanism) to Pearl.[61] And it’s no coincidence that the top two figures of the Puritan hierarchy were executors of the estate.

In Hester’s return to Boston after many years away, she is doing what Americans continue to do (especially given that she crosses the threshold back into her old cottage wearing the scarlet letter on her bosom). She’s reaching back through the A to America’s myth of national origins, and returning to the Puritans to reclaim a sense of purpose, while also demonstrating progress.

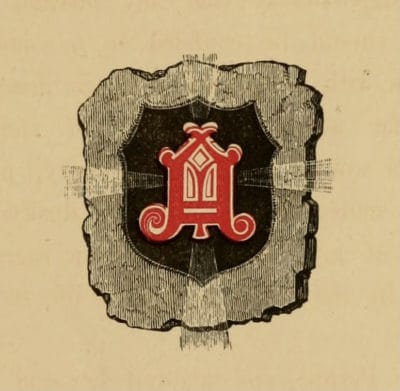

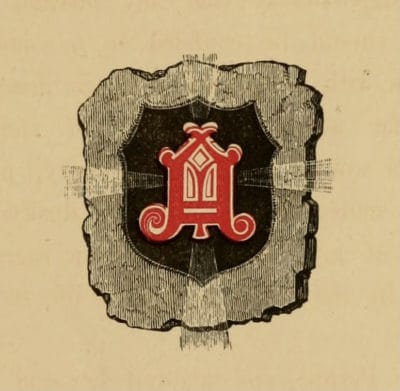

Finally, the tombstone Hester ultimately shares with Dimmesdale is engraved with an escutcheon, the shield that forms the foundation for coats of arms. And Hawthorne tells us that the motto etched into it serves as a “brief description of our now concluded legend:” [62]

On a field, sable, the letter A. gules [63]

…Sable and gules are terms used in heraldry for the colors black and red. As coats of arms are intended to do, this phrase crystalizes the cultural history of its owner.[64] The sable/black stands for the Puritanism America is grounded in, the doctrine that produced what Hawthorne describes as “black-browed” followers, and future generations continue to associate with black cloaks and steeple-crowned hats.[65] And the A once again functions as a cultural artifact, only this time not as a token of shame, but as a crest representing progress toward the nineteenth-century ethic of individual experience and self-reliance.

___

In Conclusion.

So, what does Hawthorne’s A actually stand for? Is it the adultery so many parents have found objectionable in their challenges? Or is the feminist message, with its implied antinomianism that nineteenth-century critics took issue with? Or does the A stand for America itself?

Like all well-constructed symbols, there’s a lot packed into Hawthorne’s scarlet A. So, consistent with his multiple-choice style, the answer is a paradoxical yes. Hawthorne’s A is for – Adultery, Antinomianism, and America itself.

Endnotes:

[1] James, Henry. “Hawthorne.” In English Men of Letters. Edited by John Morley. (London: Macmillan and Co., 1879), 6.

[2] Brooks, Rebecca Beatrice. “The Life of Nathaniel Hawthorne.” History of Massachusetts Blog. Sept 15, 2011; “The Paternal Ancestors of Nathaniel Hawthorne: Introduction.” Hawthorne In Salem. hawthorneinsalem.org; Hawthorne, Nathaniel. The Scarlet Letter. (New York: Penguin Books, 2016), 11.

[3] Moore, Margaret. The Salem World of Nathaniel Hawthorne. (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2001), 31; In 1662 “Robert Pike Halts a Quaker Persecution in Massachusetts.” New England Historical Society. https://www.newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/1662-robert-pike-halts-quaker-persecution-massachusetts/

[4] Hawthorne-The Scarlet Letter, 11; “The Paternal Ancestors of Nathaniel Hawthorne: Introduction.”

[5] Hawthorne-The Scarlet Letter, 11.

[6] Melville, Herman. “Hawthorne and his Mosses.” Herman Melville. Edited by Harrison Hayford. (New York: The Library of America, 1984), 1159.

[7] Howells, W. D. “The Personality of Hawthorne.” The North American Review. Vol. 177, No. 565. (Dec. 1903), 882.

[8] Hawthorne, Nathaniel. The Scarlet Letter. (New York: Penguin Books, 2016), 10.

[9] Milder, Robert. “‘The Scarlet Letter’ and Its Discontents.” Nathaniel Hawthorne Review. Vol. 22, No. 1 (Spring 1996), 21.

[10] Wendell, Barrett. A Literary History of America. (New York: Scribner’s Sons, 1900), 433.

[11] Matthieson, F. O. American Renaissance: Art and Expression in the Age of Emerson and Whitman. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1941), 276.

[12] Fields, James T. Yesterdays with Authors. (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1893), 51

[13] Coxe, Arthur Cleveland. “The Writings of Hawthorne.” The Church Review. January, 1851. Vol. 3, No. 4., 506.

[14] Sova, Dawn B. Banned Books: Literature Suppressed on Social Grounds. (New York: Facts On File, Inc., 2006), 254; Brownson, Orestes. “The Scarlet Letter.” Brownson Quarterly Review. October, 1850.

[15] Gurdon, Meghan Cox. “Even Homer Gets Mobbed; A Massachusetts school has banned ‘The Odyssey.’” Wall Street Journal (Online). Dec. 27, 2020;

[16] Coxe, 510.

[17] Brownson, Orestes. “The Scarlet Letter.” Brownson Quarterly Review. October, 1850; Sova, 254.

[18] Milder, Robert. “Nathaniel Hawthorne.” The Cambridge Companion to American Novelists. Edited by Timothy Parrish. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 14.

[19] Perotta, Tom. “Foreward.” The Scarlet Letter. (New York: Penguin Books, 2016), ix.

[20] Bercovitch, Sacvan. “The A-Politics of Ambiguity in ‘The Scarlet Letter.’” New Literary History. Vol. 19, No. 3. (Spring, 1988), 631, 632; Milder- “Nathaniel Hawthorne,” 14.

[21] “Scarlet Letter.” Massachusetts Law Updates. Nov. 30, 2013.

[22] Carrez, Stephanie. “Symbol and Interpretation in Hawthorne’s ‘Scarlet Letter’.” Hawthorne In Salem. http://www.hawthorneinsalem.org/page/12218/

[23] Bercovitch- “The A-Politics of Ambiguity in ‘The Scarlet Letter,’” 630.

[24] Bercovitch- “The A-Politics of Ambiguity in ‘The Scarlet Letter,’” 630; Bercovitch – “The Scarlet Letter: A Twice-Told Tale,” 4; Bercovitch- “Hawthorne’s A-Morality of Compromise.” Representations. No. 24, Special Issue: America Reconstructed, 1840-1940 (Autumn, 1988), 12.

[25] Noll, Mark. A History of Christianity in The United States and Canada. (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1992), 148.

[26] Sarracino, Carmine. “‘The Scarlet Letter’ and a New Ethic.” College Literature. Vol. 10, No. 1 (Winter, 1983).

[27] Neumann, Erich. Depth Psychology and a New Ethic. Translated by Eugene Rolfe. (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1973), 33.

[28] Hawthorne- The Scarlet Letter, 114.

[29] Hawthorne- The Scarlet Letter, 141.

[30] Hawthorne- The Scarlet Letter, 134.

[31] Neumann, 35.

[32] Neumann, 41.

[33] Sarracino, 52.

[34] Hawthorne- The Scarlet Letter, 63.

[35] Sarracino, 52.

[36] Hawthorne- The Scarlet Letter, 239.

[37] Hall, David D. ed. The Antinomian Controversy, 1636-1638: A Documentary History. (Durham: Duke University Press, 1990).

[38] Hawathorne- The Scarlet Letter, 152.

[39] Khomina, Anna. “The Banishment of Anne Hutchinson.” The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. (Nov. 17, 2016).

[40] Hall, 3.

[41] Pokol, Agnes. “The Sociological Dimensions of The Scarlet Letter, Hawthorne as a Social Critic on Democracy and the Woman question.”

[42] Hawthorne-The Scarlet Letter, 181.

[43] Pokol.

[44] Pokol; Emerson, Ralph Waldo. “Nature.” Ralph Waldo Emerson: A Critical Edition of the Major Works. Edited by Richard Poirier. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 2.

[45] “Transcendentalism, An American Philosophy.” U.S. History: Pre-Columbian to the New Millennium. www.ushistory.org.

[46] Milder, “Introduction.” The Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne. (New York: Penguin Books, 2016), xiii.

[47] Milder- “‘The Scarlet Letter’ and Its Discontents,” 11.

[48] Milder- “Introduction,” xxiv; Milder- “‘The Scarlet Letter’ and Its Discontents,” 12.

[49] Hawthorne- The Scarlet Letter, 153.

[50] Fuller, Margaret; Channing, W. H.; Emerson, Ralph Waldo; Clarke, James Freeman. The Autobiography of Margaret Fuller Ossoli. Vol. 1&2. (Madison & Adams Press, Kindle Edition), 326.

[51] Hawthorne- The Scarlet Letter, 245.[52] Turner, Victor. “Betwixt and Between: The Liminal Period in Rites of Passage.” Betwixt & Between: Patterns of Masculine and Feminine Initiation. Edited by Lois Carus Mahdi, Steven Foster, Meredith Little. (La Salle, Illinois: Open Court, 1987), 7.

[53] Sarracino, 57.

[54] Hawthorne- The Scarlet Letter, 92.

[55] Hawthorne- The Scarlet Letter, 84.

[56] Hawthorne- The Scarlet Letter, 47.

[57] Hawthorne- The Scarlet Letter, 184.

[58] Milder- “Nathaniel Hawthorne,” 14-15.

[59] Hawthorne- The Scarlet Letter, 238.

[60] Sarracino, 58.

[61] Hawthorne- The Scarlet Letter, 243.

[62] Hawthorne- The Scarlet Letter, 246.

[63] Hawthorne- The Scarlet Letter, 246.

[64] International Heraldry & Heralds.

[65] Hawthorne- The Scarlet Letter, 11, 217.

Images:

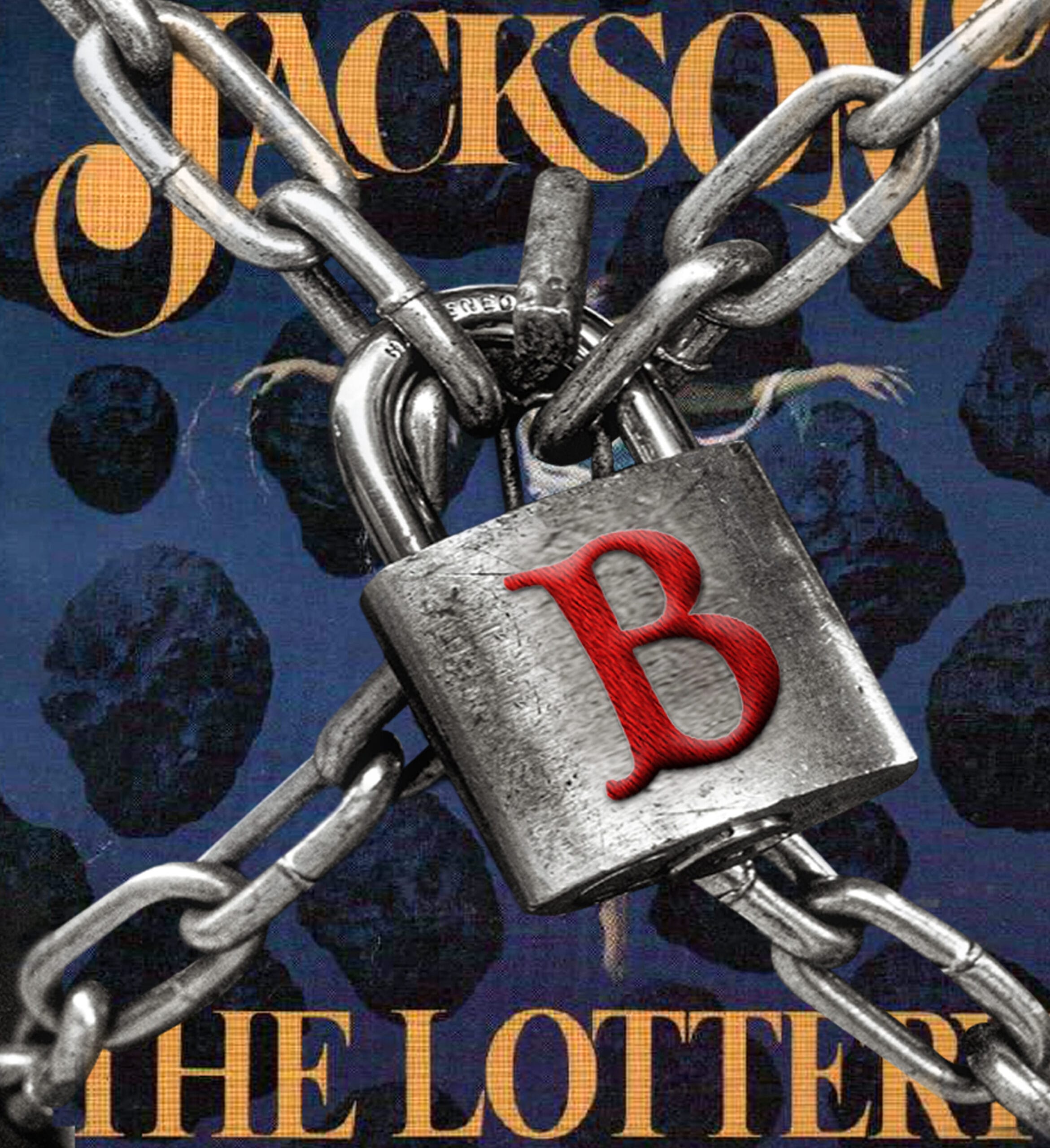

Cover. Hawthorne, Nathaniel. The Scarlet Letter. (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1895).

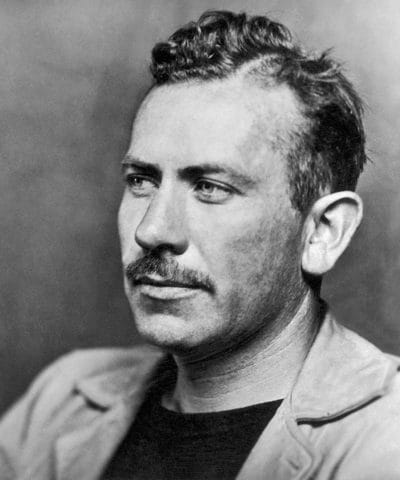

Nathaniel Hawthorne portrait. Nathaniel Hawthorne. , ca. 1860. [to 1865] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017892968/.

Anne Hutchinson Statue. Curbed Boston. https://boston.curbed.com/maps/boston-statues-of-women

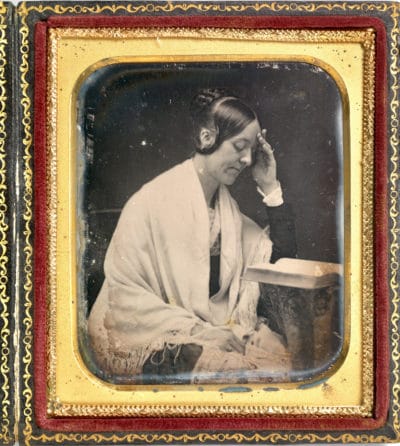

Margaret Fuller portrait. Josiah Johnson Hawes, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/39/Margaret_Fuller.tif

Illustrated images are taken from: Hawthorne, Nathaniel. The Scarlet Letter. (Boston: James R. Osgood and Company, 1878).

FYI:

This Book is Banned participates in the Amazon.com affiliate program, where we earn a small commission by linking to books (but the price remains the same to you). This allows us to remain free, and ad free. [Our privacy policy]

A

A

G

G

K

K

N

N

W

W

…

…

T

T